The Famicom Disk System, also called the Family Computer Disk System, came out on February 21, 1986, but only in Japan. This Famicom add-on came with a bunch of new games on Nintendo-branded floppy discs. At the time, floppy discs were better than cartridges in a few ways, but they also had a few problems. Even back then, loading times from discs were a problem, and you’re much more likely to find a broken FDS disc than a broken Famicom cartridge these days.

- 6 Best Pokemon RPG Maker Games That You Should Know Update 07/2024

- 9 Best Valve Games That You Should Know Update 07/2024

- 8 Best Games With Character Creation That You Should Know Update 07/2024

- 8 Best Selling Wii Games That You Should Know Update 07/2024

- 7 Best Torrent Sites For Games That You Should Know Update 07/2024

The Famicom Disk System had some games that were only available on it, like Yume Kj: Doki Doki Panic (which became Super Mario Bros. 2 in the West), Otocky, and The Mysterious Murasame Castle. However, most of its most popular games would soon be released on cartridges. In honour of its 35th anniversary, which it shares with a game at the bottom of this list, we chose eight games that came to the NES in the West that we think were probably better on FDS.

You Are Watching: Top 6 Best Famicom Games That You Need Know Update 07/2024

There’s a lot of nostalgia around NES games, and we love the western versions of almost all of the games below to death. Still, we think that the Japanese versions of these classics are a little bit better. Tell us what you think where you always do.

A warning: there will be a lot of talk about different kinds of music, extra wavetable synth channels, and save systems vs. passwords…

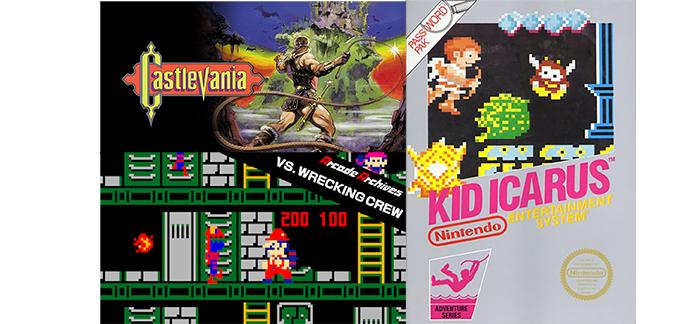

Castlevania (NES)

“Better” is, of course, a subjective word. The FDS version of Castlevania has load times that aren’t in the cartridge version because it uses discs instead of cartridges. But, all things considered, we’d rather play the original Akumajou Dracula (which came out on Famicom cartridge in 1993) than the western version because it’s easier to save your progress.

The ability to save comes with three save slots, and when you start the game, you give each one a name. At the end of the game, the name you use in the FDS version is added to the credits, which is a nice touch. For instance:

Even though it’s not a big deal, these little things might make the FDS version the best of the bunch.

Metroid (NES)

Several of the games in this list are here only because the FDS version could save your progress. Maybe you couldn’t wait to put your “Password Pak” in the slot and type in a long string of letters and numbers to get back to where you left off, but we always thought it was a waste of time. Metroid on the Famicom Disk System didn’t let you play as Samus without her armour (if you beat the game in less than three hours), but we’d rather not see the bounty hunter shooting space pirates in a pink leotard than have to write down multiple 24-digit passwords.

Read More : 7 Best Games To Play On Macbook Air That You Should Know Update 07/2024

In an interesting twist, The Cutting Room Floor suggests that Nintendo may have planned to use battery backup instead of the cumbersome password system used in the final version.

As we’ll learn more about below, the FDS’s extra wavetable synth channel gave the disc version a wider range of sounds to choose from. However, the extra onboard sound chip wasn’t available in the West, so sounds that used it had to be changed. The video below shows how the extra sound channel helped the main theme’s atmosphere, and how Samus’s appearance (at 1:00) went from an organ-like hum to a juddering warble on the NES. But the difference is less noticeable on other songs, like Brinstar (scrub to 1:14 and then to 2:00 to hear the difference on that classic).

Wrecking Crew (NES)

Wrecking Crew was not exactly a shining star in the Nintendo galaxy when it came out in 1985 on a standard Famicom cartridge. In 1989, it moved to the Disk System.

Why bring this game back for a second time on the Disk System, you might ask? Well, the original game had a level editor, but if you wanted to save your creations to an old-school cassette tape, you had to use a Japan-only accessory called the Famicom Data Recorder (also used to save custom Excitebike and Mach Rider tracks). The FDS version let you do this without needing the tape deck accessory. This was Wrecking Crew’s best chance to show off its skills.

Zelda II: The Adventure of Link (NES)

Known as The Legend of Zelda 2: Link no Bouken in Japan, the list of minor differences between Zelda II: The Adventure of Link and the 1987 FDS original is a long one; we thoroughly recommend checking out The Cutting Room Floor’s comprehensive round-up of regional differences.

But we think it’s pretty important that the Famicom Disk System version had water that moved on the overworld map. The top-down parts of the game, which were zoomed out compared to the view in the first Zelda, always seemed dull and basic to us. Even though the water isn’t moving very fast, it gives the otherwise still scene a little bit of life. It’s amazing how much of an effect one thing can have.

Then there are the differences in music. Here is a comparison of the title screens, and you can decide which one you like better…

Kid Icarus (NES)

Read More : 8 Best RPG Board Games That You Should Know Update 07/2024

As we’ve already said, save slots are great, password systems are awesome, and Kid Icarus was another FDS game that lost its saves when it was turned into a NES game, just like Metroid. The Hikari Shinwa: Palutena no Kagami version for the Disk System also keeps track of your top five best scores.

Hip Tanaka’s great music gets the usual downgrades and changes in the West, but other places also missed out on the microphone functionality built into the second controller for the Famicom. Originally, you could use this microphone and the “A” button to “haggle” with shopkeepers, presumably shouting their crazy prices down to something reasonable. There was no voice recognition going on here, of course. The mic just picked up loud noises and other sounds and recorded them.

We’ll talk about another well-known Famicom Disk System game that used the microphone in a bit. It may not be a big addition, but it’s a fun addition to an interesting, but not perfect, 8-bit game from Nintendo.

Jongbou (Famicom)

I’ve noticed some interesting patterns in “generic” games as I’ve played more and more games for the NES and FDS. RPGs tend to be copies of Dragon Quest, arcade games tend to be top-down shooters like Xevious or puzzle games like Super Breakout, platform games tend to be generic games like Super Mario Bros., and so on. Obviously, this kind of copying of formulas would eventually lead to their own unofficial subgenre (like the Dragon Quest clones) or just a general feeling of pointless repetition. At the same time, some games still fit into these categories, but they stand out in their own ways. For example, several of the games on this list are Dragon Quest clones that improved on the original formulas.

Jongbou is one of these “repetitive” games. The idea behind Jongbou is similar to that of Super Breakout and Arkanoid at first. You’ll be in charge of a paddle at the bottom of the screen. You’ll use it to move balls back and forth between the paddle and a number of blocks at the top of the screen. By removing the blocks from the level, you can earn points and power-ups, and if you remove all of the blocks, you will finish the level. Are you still with me?

That is the main idea behind games like Super Breakout and Arkanoid. There have been many copies of these games over the years, mostly for the NES, GameBoy, PC, and iOS devices, and many of them don’t go much further. At first glance, it seems unlikely to add the idea of “strategy” to this idea, unless it goes beyond basic physics, especially the Law of Reflection. And yet, this is what Jongbou does: it adds Mahjong.

Mahjong is a board game that requires a lot of planning and strategy. It’s mostly played in Asia because that’s where it came from, but it’s also been brought to other places and changed in different ways. The most popular change is the “mahjong tiles” game, in which you match pairs of tiles that look the same. Even so, the original version of mahjong in this game is more like poker than anything else. Your goal is to match up fourteen tiles, the last of which is the last tile you draw, so that every tile is part of exactly one meld and you can’t make more than one pair. The last tile you draw is the last tile you’ll match up. There can be pairs, pongs (three of a kind), kongs (four of a kind), and chows among these melds (three-tile straight). There are also more complicated melds that use the whole hand.

In the end, mahjong is much more complicated than this (the Mahjong Taisen entry goes into more detail on this), but that one paragraph is all you need to know for this game. Jongbou’s levels get harder and more boring over time, which is typical of games like this, so the mahjong part of the game is a key part of fixing this problem. Most of the blocks in the levels are actually Mahjong tiles that you can add to your hand. When you hit a tile, it flips over to show what’s underneath, and a second hit makes it fall down. If you grab it with the paddle, you have to put it in your hand, which is shown on-screen with 13 other tiles. If you ever do make a full hand of mahjong tiles, you can skip the current level.

So, it’s easy to see how Jongbou made it onto this list. The ideas behind Super Breakout were fun, but the game itself had a problem: it was repetitive. Repetition leads to monotony, which makes the game worse in the long run, no matter how good it was at first, because it gets boring to play. To understand this, think about the 2013 3DS game Project X Zone, which most of you are probably more familiar with. It was a good tactical-RPG in its own right, with an interesting battle system, but it didn’t do anything new in its more than 100 hours of gameplay, so it fell flat quickly and easily. Jongbou improved on Super Breakout by giving you a second thing to think about: the strategy of mahjong and the best way to use your hand and where the ball goes to get the right mahjong tiles. Whereas Super Breakout is only fun for a short time, Jongbou is very fun for a long time. It keeps your attention and keeps you entertained throughout the whole game because it successfully combines two ideas.

Sources: https://www.lunchbox-productions.com

Categori: Games