One of the most often asked questions about Roger Deakins’ work in Blade Runner2049 has been, “Will Roger finally win an Oscar?” Among the most remarkable features in Deakins’ work is his ability to employ color in a variety of ways.

- 10 Anime Gate Characters That You Should Watching Update 07/2024

- 10 Best Anime Characters With Dreads That You Should Watching Update 07/2024

- 25 Best Whodunit Movies That You Should Watching Update 07/2024

- Top 10 Anime Like Arifureta From Commonplace To World’s Strongest Update 07/2024

- 12 Best Pirate Movies That You Should Watching Update 07/2024

We’ve never seen anything like it, but have we?

You Are Watching: 10 Movies With The Best Cinematography That You Should Watching Update 07/2024

Today’s best cinematography compares favorably with some of the greatest color films ever made.

When “The Wizard of Oz” and “Gone with the Wind” were huge hits, color films became a staple of international cinema in the 1930s.

12 of the greatest color films of all time, spanning the decades from 1947 to 2011, have been compiled by our team of experts, including Jack Cardiff and Emmanuel Lubezki.

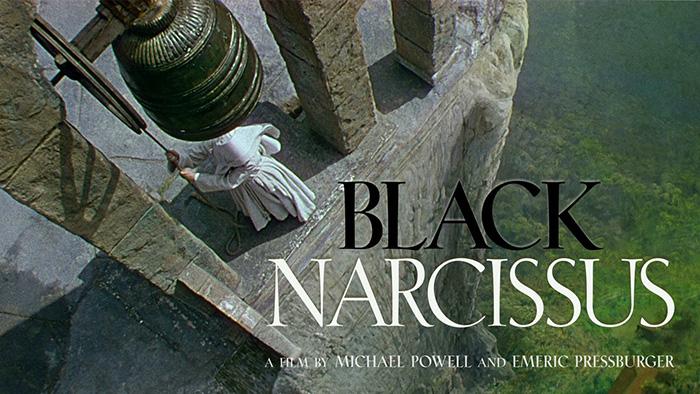

1. “Black Narcissus” (1947)

Jack Cardiff, a British cinematographer of the studio period, was unique in that his work improved when he transitioned from black and white to color. “Painterly” is an overused phrase in describing cinematographers’ work, yet Cardiff’s work is 100% fitting. With Vermeer as his inspiration, a self-taught artist created his light on the sound stage.

Though Cardiff’s use of Technicolor was far more grounded than that of his Hollywood predecessors, his pictures nonetheless had an otherworldly feel in their subdued beauty. Never more so than in Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger’s “Black Narcissus,” when he constructed an almost mythical alpine scene on a studio lot. With images that transport the audience somewhere between the heavens and the edge of Earth, Cardiff manages to make a difficult story about nuns who lose their sense of self-control in the Himalayas feel like a film that has been shot somewhere between heaven and the edge of the world.

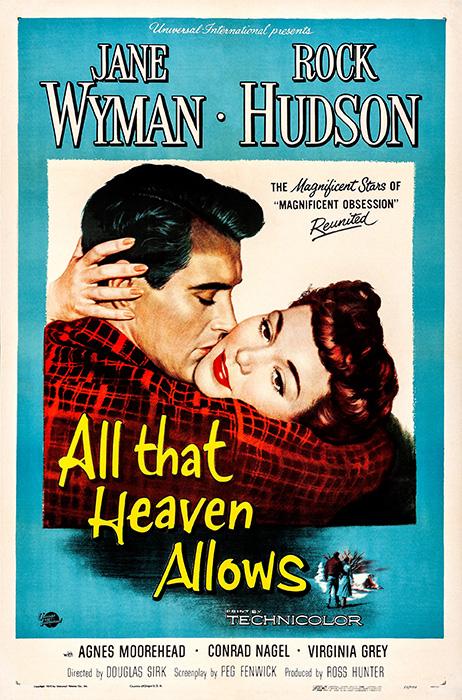

2. “All That Heaven Allows” (1955)

Read More : 10 Best Trippy Movies That You Should Watching Update 07/2024

Hollywood artisans’ ability to create stunning effects in three-strip Technicolor remains a cinematic treat. Even today, no digital technology has been able to reproduce the electrifying saturation and color separation of Hollywood’s color schemes in the studio setting.

For Jane Wyman, the suburban widow protagonist in “All That Heaven Allows,” Douglas Sirk and Russell Metty used those Technicolor candy-colored surfaces as a prison for the pressure to maintain the facade of upper-middle class perfection juxtaposed with her love of a soulful, young tree farmer (Rock Hudson). Color and low-key noir lighting would be used by Metty, who also shot Orson Welles’ classic “Touch of Evil,” to uncover the emotional truth that lay beneath the film’s bright surface.

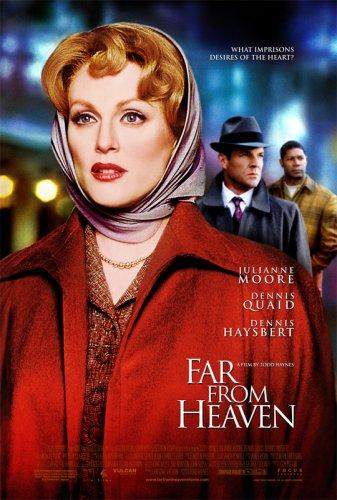

3. “Far From Heaven” (2002)

“Far from Heaven” filmmakers wanted to see how they could use Sirk’s melodrama style, so they hired DP Ed Lachman to reproduce the color palette and manufacturing studio appearance of “All That Heaven Allows” on location in New Jersey nearly half a century later.

While working with a 10-foot domestic ceiling, Lachman created an overhead grid light scheme, a stunning saturated color palette (despite the limitations of 2002 film stock), and even managed to regulate the sun to give the exteriors a backlot vibe. He is a technical marvel who does his homework. Sirk’s beauty functions as a repression device, with frames that encase the characters in a cage of their own making while portraying their emotional states in awe-inspiring hues.

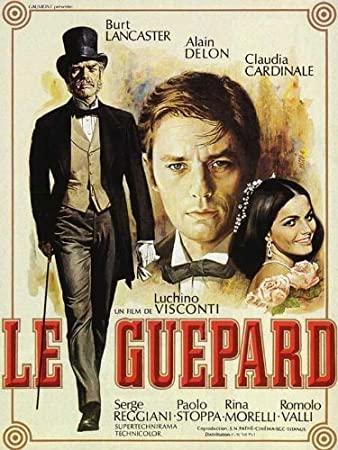

4. “The Leopard” (1963)

An ancient Italian prince (Burt Lancaster) is watching the old world traditions he adores fade away as societal unrest and the younger generation (represented by his nephew Alain Delon) have little regard for the ways of the past. Filmmaker Giuseppe Rotunno and director Luchino Visconti’s cinematography both portray this change while also eulogizing the past in their work.

With operatic grandeur and golden hues of aristocratic life, they bring to life in the ballroom scenes, while a flood of sunlight shows tangible fractures in their crumbling fortress. Restoration by a team of diehard fans including Martin Scorsese has allowed modern viewers to discover the glory of this 1963 Cannes Film Festival Palm-d’Or winner, which was slashed for release.

5. “The Conformist” (1970)

“The Conformist’s” cinematography is sometimes referred to as dreamy, although no one’s dreams are as beautiful. To put it another way, the director-cameraman pairing of Bernardo Bertolucci and Luca Storaro is a match made in cinematography heaven. In 1936, Marcello (Jean-Louis Trintignant) leads a group of fascist goons to an anti-fascist professor, whom they want to murder. Marcello recognizes through memories that his journey to moral compromise (and fascism) has been a long one, but he also realizes that he has a long way to go.

Read More : 10 Best Anime Ovas That You Should Watching Update 07/2024

As the character’s spirit slowly bleeds out, Storaro paints each of the magnificent set pieces in a particular color and tone. While the sights in Rome are drab and depressing, the scenes in Paris are loaded with vibrant color and welcoming warmth that evoke a beautiful moment. In light and color, never before has such a complex portrait of character been conveyed so expressively. It’s widely considered to be one of the greatest examples of color filmmaking.

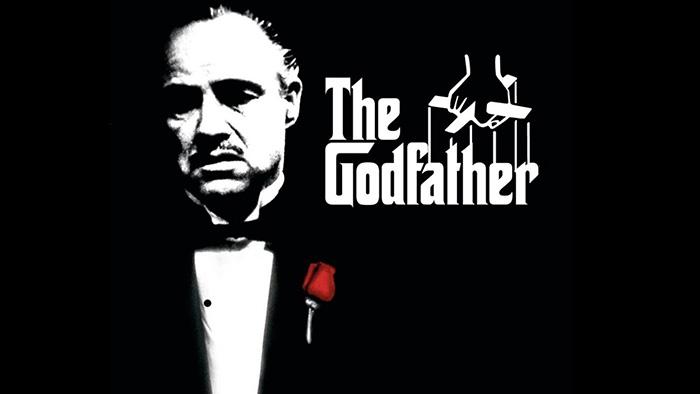

6. “The Godfather Parts I & II” (1972 & ’74)

With “The Godfatheropening “‘s sequence in mind, you can’t help but sympathize with Paramount execs when they watched it. Gordon Willis is the first cameraman to challenge the audience to stare in the dark like this. There was a strong main light that defined the most significant areas of the frame in noir lighting, even as it explored shadows. Willis, on the other hand, seemed to be challenging the principles of exposure and fundamental three-point lighting in a way that more closely resembled Renaissance paintings than any movie that had been made up to that time.

To be fair to Conrad Hall, his cinematographer and friend, Willis was more than just “Prince of Darkness,” as evidenced by the various appearances he donned in the first two “Godfather” flicks. For example, Willis created an incredible array of looks that all fit together to produce one of the most iconic films ever made, from the kodachrome wedding, to the sun-drenched love story of Michael in Sicily, to the gorgeous immigration tale of young Vito Corleone (Robert De Niro) in IB technicolor.

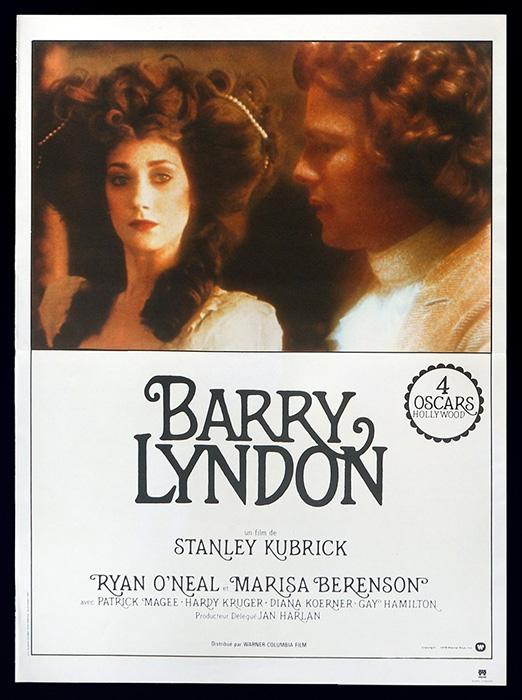

7. “Barry Lyndon” (1975)

For example, the use of 70mm, the NASA-designed lens that was so fast that candles could light the night scenes in Barry Lyndon, the incredible period accurate locations and a seemingly endless shoot allowed Kubrick to strive for perfection with his precise compositions can all be cited as examples of concrete and technical reasons for the film’s stunning beauty. That “Barry Lyndon” was merely naturalism heightened by technology and Kubrick’s formality undercuts the creativity of cinematographer John Alcott.

Extensive experimentation was required to create the single-source natural light that Alcott desired in such big rooms, which were frequently photographed in extreme wide shots and often in the winter. Alcott used mini-brute lights and tracing paper to illuminate Kubrick’s tableau-like sequences to mimic the painting of the era. With a clarity that transcended the hazy lighting of the time, he also managed to capture the misty ambiance of Ireland’s rural landscape. Only because of what Alcott brought to the frame did Kubrick manage to enthrall his audience with the film’s languid pace.

8. “Heaven’s Gates” (1978)

Nestor Almendros’ stunning “Days of Heaven” appears to have been shot at the peak of the magic hour, when the light couldn’t have been more beautiful. The fleeting beauty of the Texas panhandle environment, as well as the whimsical narration by young Linda Manz and the enchanting score by Ennio Morricone, dwarf the earthbound drama caused by Richard Gere, Brooke Adams, and Sam Shepard’s perilous love triangle.

His second picture was widely regarded as an exercise in shooting beauty, but during his 17-year absence from the film industry following “Heaven,” the cinema world realized that there was an even greater poetry being expressed through the musicality of movement and light. Seeing the beautiful and disciplined visuals of Almendros meticulously stitched together around a more cohesive story, it remains the highest achievement of Malick’s ability to tell stories through light.

Sources: https://www.lunchbox-productions.com

Categori: Entertaiment