In anticipation of Yann Demange’s celebrated debut at the London Film Festival, ’71, we take a look at some of the best Troubles-related films.

- 11 Best Movies About Beer That You Should Watching Update 07/2024

- Top 12 Shows Like Hawaii Five O That You Need Watching Update 07/2024

- 14 Best Movies About Doctors That You Should Watching Update 07/2024

- 10 Best TV Shows Like Resident Alien That You Should Watching Update 07/2024

- 7 Best Movies About Hypnosis That You Should Watching Update 07/2024

Two months ago today.

You Are Watching: 10 Best Movies About The Troubles That You Should Watching Update 07/2024

By Alex Davidson.

“71,” which had two sold-out showings at the London Film Festival, will be released to UK theaters on October 10th. As a young British soldier (Jack O’Connell) is caught behind enemy lines after being separated from his unit, he must find a way to escape the Provisional Militia and choose whose loyalist comrades he may trust. At the Festival, it will be shown in the First Feature Competition section.

“The Troubles” is the latest in a long line of films on Northern Ireland’s political strife that raged for decades beginning in the late 1960s. During the late 1960s and early 1970s, the majority of Troubles films were documentaries, such as A Place Called Ardoyne (1973), which featured interviews with residents of a working-class Catholic community. An Oscar-winning documentary on the Vichy government’s involvement with Nazi Germany, The Sorrow and the Pity (1969), was weak, and naive in its seeming support for the IRA, A Sense of Loss (1972).

Get the most recent BFI news here.

Receive BFI news, features and podcasts by signing up.

Troubles were better shown on television in the 1980s rather than at the movies. Alan Clarke’s Contact (1985) and Elephant (1989) depicted the brutality of the fight, while Harry’s Game (1982) gave us Clannad’s theme tune, which has been used to soundtrack endless newsreel footage of the conflict ever since. As the most controversial of them, the This Week documentary Death on the Rock (1988) presented overwhelming evidence that three IRA soldiers murdered by the British troops in Gibraltar were unarmed at the time of their deaths. Much tabloid hysteria ensued, and attempts were made to damage the reputations of crucial witnesses. The British government was unimpressed.

Both in the United Kingdom and Hollywood, Troubles-inspired thrillers began to appear in the 1990s, with IRA soldiers serving as villains and antiheroes in The Jackal (1997) and The Devil’s Own (1997), respectively. As a result of the success of Lock, Stock & Two Smoking Barrels and its ilk, films like Resurrection Man have unintentionally glorified violent gangsters (1998). With Helen Mirren’s affecting performance in Some Mother’s Son (1996), and Julie Walters’ undervalued Titanic Town (1999), the role of motherhood became more prominent in the 1990s (1998).

Since the signing of the Good Friday Agreement in 1998, films on the Troubles have remained a source of inspiration for filmmakers, whether they’re black comedy, thrillers, or intimate character studies (Five Minutes of Heaven, 2009). This decade’s conflicts have been depicted in countless films, but these ten take a fresh look at a time that forever reshaped the United Kingdom.

Instead of looking at the conflict as a whole, these videos focus on the time between 1968 and 1998. A futurelist can draw inspiration from a wide range of films made during this time period, including those set during the Irish Civil War and partition in the early 1920s.

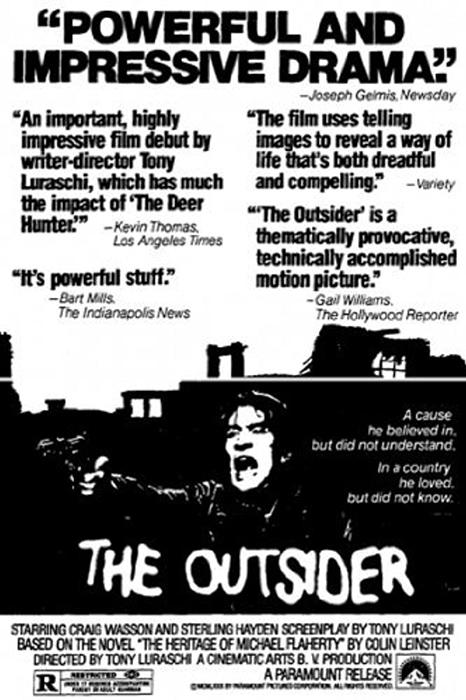

1. The Outsider (1979)

Read More : 10 Best Mysterious Anime Characters That You Should Know Update 07/2024

IRA fighters send a Vietnam veteran (Craig Wasson) straight to Belfast, hoping that he’ll be killed by the British Army to cause international outrage and encourage financial support from supporters in the United States, but he has no idea how complicated the struggle is and finds himself being targeted by both sides.

A scene in which a blind pacifist is tortured by a British officer sparked controversy and was the only sad case of the film going over the edge into sensationalism. Even though most of Belfast was re-created in Dublin, some scenes were shot while driving around the city and made it into the film. The depiction of Belfast as an alien urban battleground and the inability to sympathize with any side makes for a riveting and unnerving viewing. In keeping with his status as an outsider, Wasson’s idealistic and gung-ho demeanor lends itself ideally to a gauche hero.

2. Maeve (1981)

Mary Jackson, a young woman who returns to her home in Belfast after living in London for years, is the subject of Pat Murphy’s forgotten drama, which is a feminist work that examines the representation of the Troubles and history itself from a female perspective. Angry by the petty sexism of her republican boyfriend’s fixation with the past and his notion that women get “remembered out of existence,” Maeve fights passionately with her feminist sister (an early appearance by Brid Brennan) over their feminism.

With its striking imagery, strong and engaging characters, and a poetic and tragic rendering of memory that would be seen later in the work of Terence Davies, Maeve is unlike many feminist films of the day. It’s witty and provocative, with phrases like “men’s connection to women is just like England’s relationship to Ireland.”

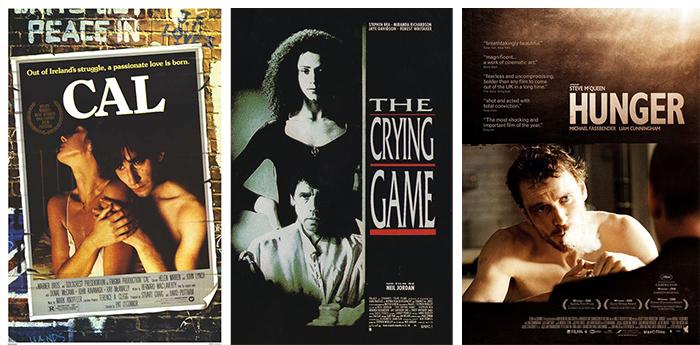

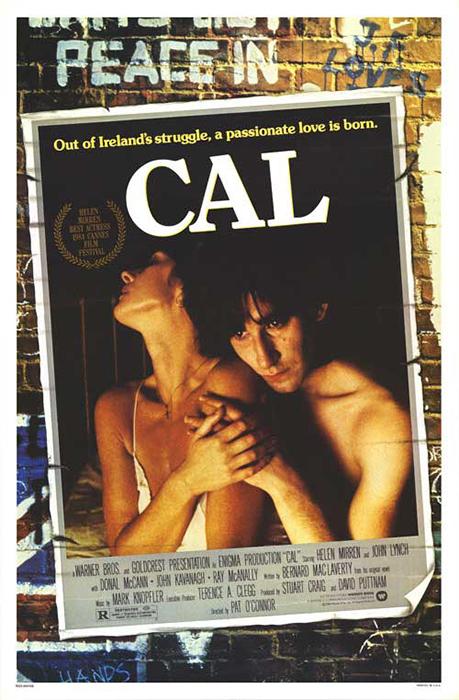

3. Cal (1984)

An unseen assailant shoots and kills a member of the Royal Ulster Constabulary in a slasher horror film-style opening sequence. We learn that Cal (John Lynch), a young IRA soldier with little appetite for violence, drove the getaway car used in the murder, but the tone mellows as we follow his life. He is a despicable figure, tormented by IRA thugs and harassed by loyalist thugs in his own home. He tries to apologise for his actions by working for the widow (Helen Mirren) of the man he killed.

Pat O’Connor’s film sensitively depicts the dreadful repercussions on the families of the victims and the fighters themselves of sectarian conflict. Mirren’s powerful performance as a lady dealing with bereavement, rage, and a new romantic interest won her the Cannes best actress award, while Lynch’s overlooked film debut is terrific.

4. Elephant (1989)

Contact (1985), Alan Clarke’s first television film about Northern Ireland’s Troubles, is his most grim and relentless effort. To reflect the tragic human cost of the Troubles, it presents 18 homicides without purpose or conversation and lingers on each victim’s corpse to confront the viewer with the brutality of the violence. Titled after a phrase by the Irish writer Bernard MacLaverty, who likened the Troubles to having an elephant in the living room that you had to learn to live with despite its constant presence.

What prompted Gus van Sant to make 2003’s Columbine-inspired film, which won Cannes’ prestigious Palme d’Or award, was greatly influenced by this book. One of Danny Boyle’s first productions, Clarke’s picture remains one of the most evocative of the war. Although news reports and lesser films have glamorized or sanitized violent acts, movie exposes the unending cycle of violence as it truly is: numb, inhuman and pitiless.

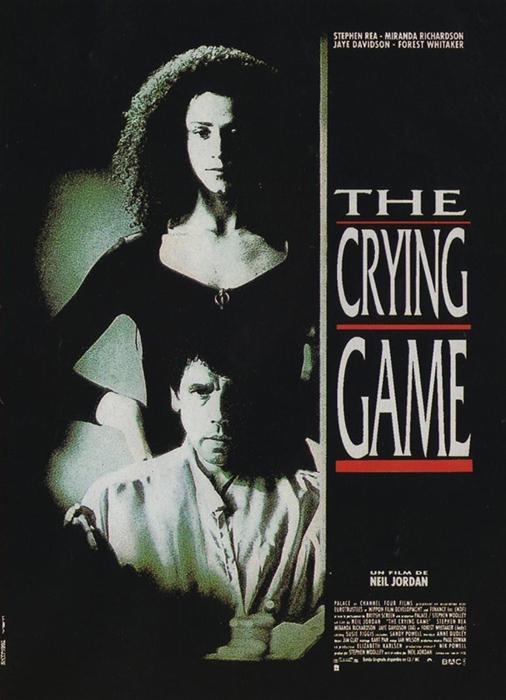

5. The Crying Game (1992)

However, even if you have yet to see “The Crying Game,” you’re likely already familiar with one of the film’s many plot twists, even if you don’t realize it. Neil Jordan’s Oscar-winning picture, about Fergus (Stephen Rea), an IRA fighter whose life is permanently changed after kidnapping a British soldier at a South Armagh funfair, has many other compelling reasons to see it. It is a shift from thriller to unexpected romance when Fergus’ past reappears in London after an intense first third of the novel.

Previously, Neil Jordan had written about the Troubles in Traveller (1981) and Angel (1982), both of which portrayed Rea, the deaf-mute girl’s saxophone, in the hunt for the loyalist killers of a deaf-mute girl. There’s no denying that The Crying Game is the most intriguing of the bunch, presenting an original spin on the classic Troubles themes of masculinity, brutality, and devotion.

6. In the Name of the Father (1993)

Read More : 10 Best Non Ghibli Anime Movies That You Should Know Update 07/2024

“The Guildford Four,” Jim Sheridan’s follow-up to My Left Foot (1989) and The Field (1990), depicts the Guildford Four’s trial and subsequent acquittal after they were convicted of the 1974 pub bombings in a blatant miscarriage of justice. Daniel Day-Lewis and Pete Postlethwaite star as Gerry Conlon and his father, Giuseppe, who sadly perished in prison in Sheridan’s angriest picture.

But despite the fact that it exaggerates the importance of lawyer Gareth Peirce (Emma Thompson) in removing the guilt of those wrongfully imprisoned, the film is an important political statement that was awarded the Berlin Film Festival’s Golden Bear for its outrage over a grave injustice. Oscar nominations went to Sheridan, Day-Lewis, Postlethwaite, Thompson and the film itself.

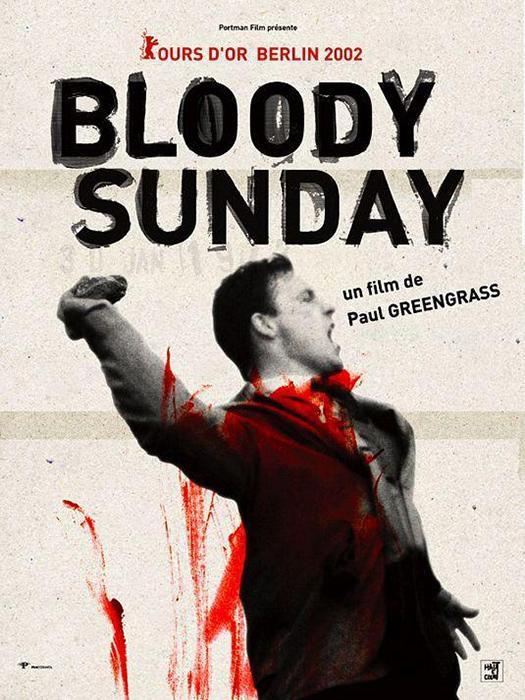

7. Bloody Sunday (2002)

Bleeding Sunday, the death of 14 unarmed demonstrators in Bogside, Derry during a march for civil rights, is one of the most horrific events in British history. The politician who organized the march is played by James Nesbitt (in career-best form) in Paul Greengrass’ film, filmed for TV but released in theaters. Don Mullan, whose book Eyewitness Bloody Sunday sparked a new investigation into the catastrophe following the perceived whitewash of the previous trial, has a supporting role in the film.

Even at this early stage of his career, Greengrass’s characteristic style, which relies heavily on handheld cameras, can be clearly seen. For his second film, Omagh, he wrote and directed the documentary about the 1998 IRA bombing of the Northern Irish town, which killed 29 people. While Captain Phillips (2013) and the Bourne Identity sequels (2004-7) have garnered more accolades and grossed more money at the movie office, Bloody Sunday remains Greengrass’s finest effort and, like In the Name of the Father, received the Berlin Golden Bear.

8. Mickybo and Me (2004)

While Mickybo and Me isn’t for everyone, it’s an excellent family picture about a young Protestant (Niall Wright) and Catholic (John Joe McNeill) friendship in Belfast in 1970. If you remove some of the pitch dark humor and cussing, it’s a wonderful family film. We see them both grow infatuated with the movie Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969). They flee with a stolen rifle, intending to live as outlaws after tiring of the hatred and bullying of their peers. Setpieces from the western are brought to life by the re-creation of major scenes in Northern Ireland.

In the aftermath of a bomb assault, Mickybo discovers a dismembered finger with an expensive ring on it. He discards the ring and takes the finger in his hand to show his joy at finding a treasure. Child stars Wright and McNeill are great, while Adrian Dunbar, Julie Walters and Ciarán Hinds provide wonderful support for their parents.

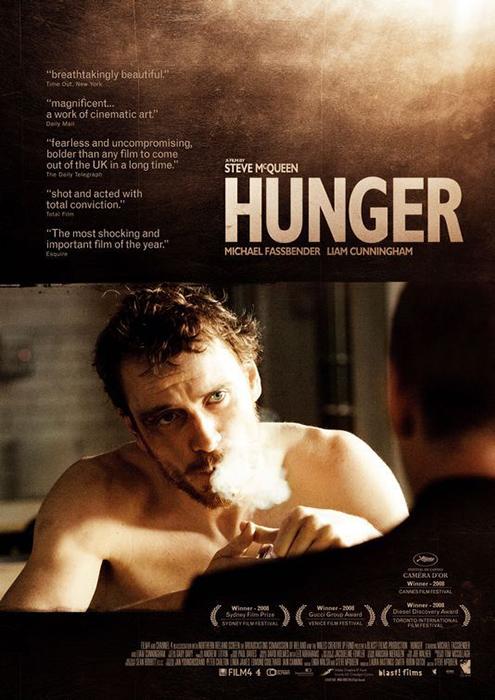

9. Hunger (2008)

After a 66-day hunger strike to protest the British government’s refusal to provide political rights to Republican prisoners, Bobby Sands died in the grip of starvation in this powerful depiction directed by Steve McQueen (Shame, 12 Years a Slave). An almost silent depiction of the Protracted Kesh prison revolt, its violence, and repression is powerful, but a long and superbly acted debate between Sands (Michael Fassbender) and a priest (Liam Cunningham) is electrifying. While the British officers are represented to be under constant fear of death and trauma, this portrayal is accurate.

At Cannes and Venice, Hunger won Best Film and Best Actor prizes and was nominated for a BAFTA as well as being named Sight & Sound’s Best Film of 2008 for Michael Fassbender. He has since worked with McQueen on all of his subsequent films. British cinema has never seen anything quite like it.

10. Good Vibrations (2012)

Many music biopics are tiresome, full of outdated male fantasies of cool, drug-fuelled shenanigans with blokey rock bands before everyone burns out, and crammed with clichés. Terri Hooley, the founder of the Good Vibrations record shop and label in Troubles-ridden Belfast, is the subject of Good Vibrations, a documentary that chronicles her story. Among the greatest pop songs ever created, The Undertones’ Teenage Kicks is still a standout in this film.

Richard Dormer’s portrayal of the impresario, Hooley, is the best part of the film, as he seamlessly mimics Hooley’s unmistakable Belfast rasp. Iconic punk band Hooley croons to a boisterous throng at the end: “London has the clothes, New York has the hairdo, but Belfast has the reason.”

Sources: https://www.lunchbox-productions.com

Categori: Entertaiment