Controversially, movies have traditionally depicted convicts in a positive light. To use Blake’s description of Milton’s party, the big screen is a big fan of bad guys, even though it knows it. However, crime and transgression are also common themes in both fiction and reality. Scarface (1932) brought us Paul Muni’s criminal sociopath Tony Camonte, who was wonderfully reimagined by Brian De Palma in 1983 with Al Pacino as the central character.

- 12 Best TV Shows Like Blackish That You Should Watching Update 07/2024

- 10 Best Evil Anime Girl Names That You Should Watching Update 07/2024

- 10 Best Movies Like Atonement That You Will Enjoy Watching Update 07/2024

- 15 Best Medieval Movies That You Should Watching Update 07/2024

- 7 Best ST Patrick’s Day Movies That You Should Watching Update 07/2024

Unlike courtroom dramas like Twelve Angry Men, which formally endorsed the letter of the law, the gangster genre depicted how criminal networks operated within their own rigid moral codes. However, the noir genre of the 1940s and 1950s discovered criminality not in dynastic civilizations or parodic social standards, but in individual actions of cynicism, obsession, and desperation.

You Are Watching: 10 Best Movies About Crime That You Should Watching Update 07/2024

In the caper genre, crime is made fun of, like in The Italian Job, whereas in the Ealing comedies, murder is made bitterly funny and the entrepreneurial boldness of criminals is celebrated with a nauseating jubilation.

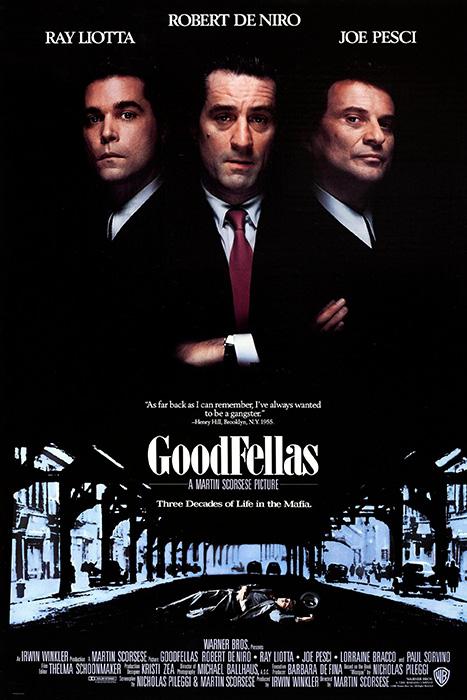

10. Goodfellas

In the last two decades, has Martin Scorsese made a greater picture than this visceral insider’s portrayal of life in the New York mob, based on Henry Hill’s true story? It’s impossible to dispute the sheer explosive impact of Goodfellas, even 20 years after its premiere, regardless of its morals or the claim that it glorifies the mafia. The movie is mainly about the attraction of the mafia. Henry Hill, the character played by Ray Liotta, admits it right from the start: “Throughout my entire life, I’ve always wanted to be a criminal. It was better for me to be an organized criminal than to be an elected official.”

Joining the mob in an impoverished Brooklyn neighborhood gives this young, half-Sicilian, half-Irish kid access to a world where everything is for sale. It connotes well-groomed guys in flashy cars, timepieces made of gold, and stunning women. Being able to strut through the kitchens of the Copacabana with your lover as a table is being set up in front of you is one of the most iconic cinematic moments ever depicted by director Martin Scorsese in The Godfather Part III. One of the many pleasures here is Michael Ballhaus’s photography. The two-and-a-half-hour film’s blazing pace is thanks to Thelma Schoonmaker’s editing, which is noteworthy for its use of jump cuts and freeze-frames.

Robert De Niro as Henry’s mentor Jimmy Conway and Joe Pesci as his partner-in-crime Tommy DeVito are two of the film’s most impressive cast members. How quickly the good life may be replaced by horrific brutality is shown by DeVito. In the late 1970s, Henry’s downward spiral into drug usage and paranoia exposes an even more gloomy view of criminality, which is revealed throughout the film. However, we are left with the overwhelming sensation that becoming a mobster has an irresistible allure. When Henry, who is in witness protection, complains about life as a “ordinary nobody” in the closing scene, the message is clear. This is either the film’s fatal weakness or its greatest achievement. A.K.A. The Fox

9. Hidden

A long, motionless view of a house on a calm Paris street serves as the film’s prologue. The credits have been shown. There isn’t much going on. The camera follows the man as he leaves the residence in a closer shot. A brief conversation is exchanged. Suddenly, we realize we’ve been viewing a surveillance footage on the screen, which is a little disconcerting. The video has arrived at the home of the couple we saw on the screen, and they are watching it with us. There is no explanation for its arrival. A well-known TV intellectual, Georges (Daniel Auteuil), and his wife Anne (Juliette Binoche), a book publisher, star in this film. An immediate sense of danger is conveyed by the video’s content. Crayon drawings depicting scenes of gruesome bloodshed arrive with the latest batch of recordings. As a result of these intrusions, Hidden takes on the tense air of a thriller while eschewing the tropes that usually characterize the genre. There is no music to set the mood. Violence that shocks us comes without a long buildup, and the victim is who we least expect.

Georges discovers a run-down flat belonging to Majid, an Algerian guy he formerly knew as a child. That Georges takes responsibility for this man’s fate reveals a larger disease in French culture surrounding the Algerian conflict, which is evident in Georges’s sense of shame. It examines Western perceptions of Islam and the Muslim world, revealing how much of our apprehension stems from unresolved guilt and shame. It never detracts from the chilling dramatic effect and the aura of suspense that builds in the last scene.

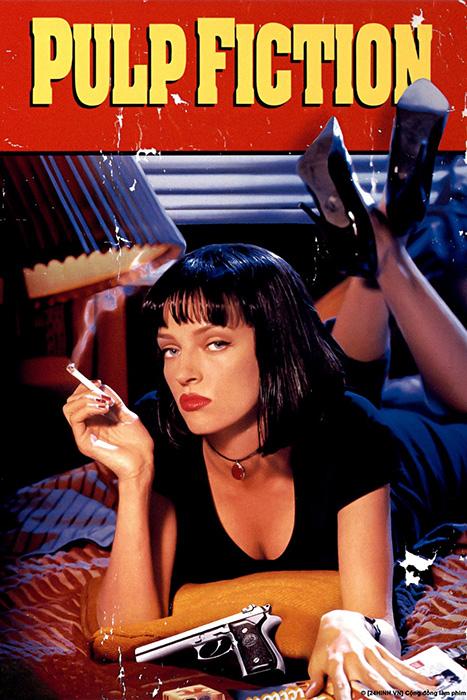

8. Pulp Fiction

It’s safe to say that 1994 was a big year for Quentin Tarantino. As a result of the shock of Reservoir Dogs two years prior, he had the opportunity to claim the title of “world’s coolest film director.” Pulp Fiction, his ambitious yet strangely sluggish second picture, opened at Cannes and won the Palme d’Or from Clint Eastwood’s jury. A year later, it had raked in $213 million, competed against Forrest Gump at the Oscars, and put a complete library of odd references and quotable phrases in the minds of moviegoers…. A phenomena, in other words, would not be an exaggeration.

Tarantino and his old video shop coworker, Roger Avary, came up with the concept of a portmanteau crime picture (who got a “story by” credit). Anti-chronological structure allows the film’s three stories to cross in unexpected ways, so that the final one takes place prior to its predecessors, and a character who died in the middle story reappears at its conclusion, striding off toward a death we’ve witnessed but which he can’t possibly know about. When Vincent (John Travolta) takes possession of a mysterious bag in the opening chapter, he goes on to chaperone his boss’s girlfriend (Uma Thurman) on an evening that spirals out of control. The second story revolves around a boxer named Butch (Bruce Willis), who gets himself into a world that can only be characterized as horrific because he doesn’t fight like he is told. While Vincent and Jules deal with a misfired gun that causes a mess in their car, the Wolf (Harvey Keitel) from a sitcom unexpectedly shows up in the final episode. All of this is set against the backdrop of a diner heist, which is being carried out by two rambunctious young criminals (Tim Roth and Amanda Plummer).

Whatever one’s opinion of the film, it did a lot for Miramax, John Travolta, and Quentin Tarantino’s careers. As the excitement subsides, it’s becoming easier to view the movie for what it actually is: an audacious attempt to blend visual chutzpah and vast storytelling, cinema and music, art and garbage into one bold package. It’s a one-of-a-kind piece. Ryan Gilbey is the individual I spoke with.

7. Get Carter

Read More : Top 10 Movie Like Battleship That You Should Watching Update 07/2024

Get Carter is as valuable as a piece of social history as it is as a thriller, even at a distance of over 40 years. Rather than depicting hen celebrations in Bigg Market, this Tyneside shows a city impoverished to the point of desolation, with no hope for improvement in sight. Even as mayhem erupts in the foreground, it appears as if Mike Hodges has plunged his actors into real life with the faces of the old men in the pubs and betting shops and the revellers at the dancehall.

In terms of tension and suspense, it’s unlike anything British cinema has produced before or after; the tone is so unrelenting that the viewer doesn’t even question whether Michael Caine truly could be a Geordie hood returning home for his brother’s funeral. When Carter’s lover’s husband (played by Britt Ekland) comes in on her having phone sex with Carter (played by Britt Ekland), he asks, puzzled: “What’s going on here? Is there something wrong with your stomach?” When Carter investigates his brother’s death, he discovers that the dead man’s daughter has been forced to star in porn films by the local crime organization, setting Carter off on a vengeance quest. This is perfectly appropriate for the subject matter.

A central figure is Caine who plays with such cool authority that even his most geezerish moments are rendered inert by his commanding presence “In spite of your size, you appear to be in poor health. It’s a full-time job for me. Now that you’ve had a chance to calm down, “– keep their ominous undertones, even if they’d gone over the edge into self-parody by now. Cliff Brumby is played by Bryan Mosley as a hapless hanger-on who makes one of British cinema’s most memorable departures, from the upper storeys of Trinity Square car park in Gateshead. John Osborne plays an unusual but utterly convincing ganglord.

Watching Get Carter right now is like reading about the first Westerners to cross the Gobi Desert: did this planet ever exist, and at such a recent time? time? time? Even if its themes of compelled sex and absolute amorality fit with present anxieties, it appears to have been written in a bygone era. In the Person of Michael Hann

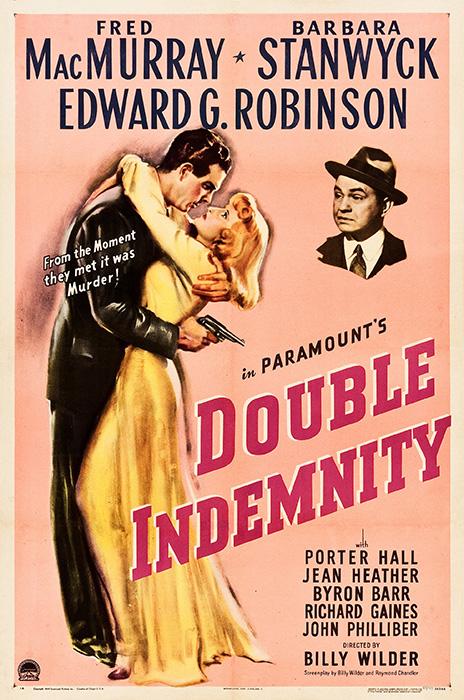

6. Double Indemnity

In Double Indemnity, Cameron Crowe dubbed it “flawless film-making”. In Woody Allen’s opinion, it was “the finest movie ever produced”. Even if you don’t agree with that, you can’t deny that it is the greatest film noir of all time, even though it was released in 1944, before the word “film noir” was even established. Regardless. Billy Wilder and Raymond Chandler collaborated on a film adaptation of James M. Cain’s 1935 novella about a straight-arrow insurance salesman seduced into murder by a dishonest housewife. A “mess,” but capable of crafting an elegant statement, was how Wilder described Chandler. Although Wilder stated that he was going for a “newsreel” appearance, noir’s visual style, which had its roots in German Expressionism, was forged here. He stated, “We had to be realistic.” You had to have faith in the circumstance and the personalities to keep from being deceived.

Isn’t it? Fred MacMurray, who had previously worked primarily in comedy, was an excellent choice for the role of the big dope in this film. “How could I have known that murder may sometimes smell like honeysuckle?” wonders Walter Neff, the hapless narrator in flashback. Neff’s coworker, a claims adjuster, is played by Edward G Robinson, who is both coiled and charismatic. However, Barbara Stanwyck’s portrayal of Phyliss Dietrichson, complete with a “honey of an anklet” and a platinum wig, is the film’s ace in the hole. In order to look like the ultimate predator, she lowers her shades. She’s also a psychopath, not just a vampire. The close-up on Stanwyck’s face as Neff kills Phyliss’s husband in the backseat of a car is one of cinema’s most horrific moments. Beware, Miklós Rózsa’s fretful strings tell us throughout the film. “I was a little terrified of it,” Stanwyck admitted when asked about the job. If she was an actress or a mouse, Wilder inquired about it. His response to her decision was: “Then take the part,” RG.

5. Rashomon

A bandit rapes a woman in the forest and murders her samurai husband. As evidence in court, the woman and her attacker present conflicting narratives of what transpired, while the dead guy, via a medium, offers another contrasting view.. A fourth eyewitness, a woodcutter, claimed to have seen the attack firsthand. What’s more, who’s telling the truth? Akira Kurosawa was at the height of his talents with Rashomon, which won the Grand Prix at Venice and the Oscar for best foreign language film. Kurosawa worked with his frequent collaborator, the imposing Toshiro Mifune. Since it was released more than half a century ago, Rashomon has had a significant impact on film structure and lexicon, presenting the truth as a nebulous concept.

However, the film’s visual eloquence and Kazuo Miyagawa’s remarkable cinematography should not be overshadowed by the film’s formalist significance, which is used as a metaphor for the story’s convoluted emotions. Using an artistically fashioned play of light and shadow, Kurosawa was able to depict the peculiar impulses of the human heart, which he adapted in part from a short story, Yabu no Naka (In a Grove), by Ryunosuke Akutagawa, for the film. … in the picture, people who went astray in the thicket of their emotions would end up in a larger wilderness….”

From Kurosawa’s desire to reconnect with the roots of the art form, which he feared were in danger of becoming eclipsed, the bristling beauty of the picture evolved. “Silent movies, he claimed “thought we had lost and forgotten what was so lovely about the ancient silent pictures” since the introduction of talkies. I was acutely conscious of the deterioration of my appearance, and it was a source of constant anger. I felt compelled to return to the film’s roots in order to rediscover its unique beauty…” The final nod to truth and ideals may be a little too soothing for some people’s tastes. Rashomon, probably Kurosawa’s greatest movie, is able to compensate for this by putting the viewer through a grueling psychological workout.

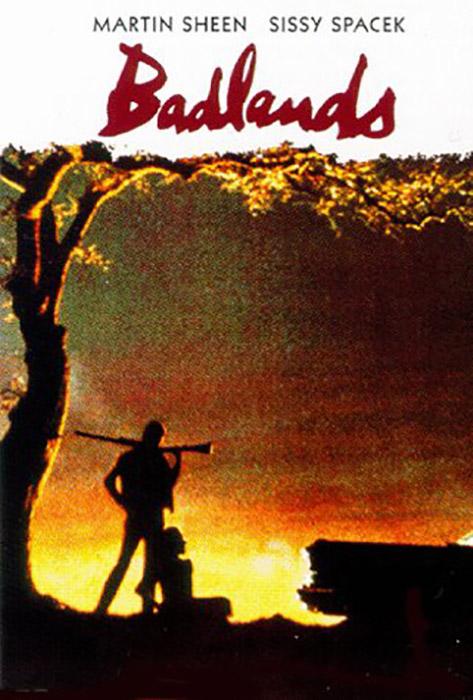

4. Badlands

Charles Starkweather, a young James Dean want tobe who went on a murdering rampage with his 14-year-old girlfriend in tow, was the inspiration for Terrence Malick’s poetic debut. Bonnie and Clyde and other pulpy true-crime tales aren’t what this picture is about. One of the best films ever made about the nexus of crime, romance, and myth-making in the United States, it is a true original in its use of color, editing and voice-over techniques. Martin Sheen, who played Kit, the Starkweather surrogate, thought Badlands was the best script he’d ever read before being cast. His reply is “Still is,” as he continues. “It was hypnotizing to watch. It took your weapons away from you. Even though this was a timepiece, it had universal appeal. You could immediately identify with the people and culture in it because it was so American-sounding.” ‘Holly,’ the baton-twirling high school student who runs away with Kit after he kills her father, was played by Sissy Spacek (Warren Oates).

Holly’s monotonous narration is largely responsible for the film’s misplaced emotional effect. What we see and hear in Badlands is characterized by a symbiotic relationship that can’t be explained by a traditional voice-over. When Kit shoots down Holly’s father, Holly’s lack of reaction is more frightening than any frantic identification. Malick remarked, “She isn’t indifferent about her father’s death.” “Despite the fact that she may have shed a few tears, she won’t tell you about it. It wouldn’t be appropriate in that situation. She has a strong, though mistaken, sense of decorum, so you should constantly get the impression that she’s leaving out a lot of what she’s been through.” That Malick is more likely to focus his camera on a quivering blade of grass during dramatic moments rather than a human face is essential for appreciating his work.

3. Vertigo

Vertigo’s reputation is now as certain as that of Citizen Kane, but what an oddball it is. D’Entre les Morts, the 1954 novel by Pierre Boileau and Thomas Narcejac adapted for the screen, isn’t the tightest of scripts when looked at as a typical thriller. In addition, there is the well-known “outside the box” twist of revealing the twist a long way before the finish. In Vertigo, plot is secondary to the machinations of desire and obsession, and there is no better film about that.

Read More : Top 15 Movies Similar To Taken That You Should Watching Update 07/2024

To follow the wife of an old friend around San Francisco in a bewildered funk, Scottie (Kim Novak), an acrophobic private spy, gets an unexpected assignment: to follow Madeleine (James Stewart). Scottie quickly finds himself lost in his own reverie as well, since she appears to be under the influence of a long-dead ancestor named Carlotta, who committed suicide.

Now that the story has taken an unexpected turn, Vertigo has descended into a darker and even more unnerving realm. Unlike Henry Fonda in Once Upon a Time in the West, Stewart’s depiction as a prototypical stalker is particularly unnerving as we witness his gentle features harden and his benign character become twisted and distorted. While Novak’s tombstone-grey outfit is a model of troubled beauty, she is also a sex symbol. To some extent, her natural anxiousness informs the fragility of her character, as evidenced by her painful question to Scottie: “If I let you alter me, would you still love me?” Why else would the picture “reveal not merely the fraudulence of romantic love, but also the entire Hollywood narrative tradition that underlies it,” as the writer David A Cook put it?

It is in this film that Hitchcock displays his most expressionistic work stylistically, including the famous zoom-in/track-out shot, also known as the “trombone shot” (and later appropriated by Steven Spielberg for Jaws), which gives the impression of moving simultaneously toward and away from a subject. Scottie’s disembodied face floating in a psychedelic abyss can’t be overshadowed by John Ferren’s nightmare scenario, which features Scottie’s disembodied face in a swirling, swirling psychedelic void.

2. Touch of Evil

The protagonist of Whit Masterson’s novel Badge of Evil, from which this film takes its cues, is an American married to a Mexican woman (in a marriage that is nine years old). That new marriage was made possible by Orson Welles, who switched the race mix. There are three distinct frontiers in the film: the Mexican-American border, the transformation of an excellent police officer into an unreliable one, and the question of interracial sexuality. Charlton Heston’s Mike Vargas and Janet Leigh’s Susie are clearly familiar, yet in 1958, that bond shocked many viewers. Honeymoon has an undertone that sets the stage for rape threats. Will the border scum get to Susie first, or will Mike get there first? If you’re still not convinced, consider how the car bomb goes off just as the newlyweds are about to have their first kiss on American soil. Coitus interruptus must be included in the charges in this criminal film.

It’s a film about crossing over, both metaphorically and cinematically, as we follow the protagonists as they cross the border in one lavish camera setup. Though it’s a well-known photo, the solitary setup in a confined motel suite that reveals how Hank Quinlan (Welles himself) dumps dynamite on the man he intends to frame is no more rich than that. This was a way for Welles to declare “I’m still the best,” but they are also fundamental to the unease that permeates the picture and the gleeful panorama of an unwholesome society. The city officials are dishonest; the night man (Dennis Weaver) needs a rest home; and the gang that comes to the motel to kidnap Susie are one of the first warnings of narcotics in American films. Not to mention Quinlan, the sheriff who has gone to hell on the basis of candy.

A “fingertip” of wickedness is not enough. A person’s DNA is tainted with wrongdoing. In the film Tanya, Marlene Dietrich’s Tanya serves as a gloomy reminder that there is no light at the end of the tunnel. That boundary remains a sore spot more than half a century later. David Thomson is the person responsible.

1. Chinatown

Hokusai waves break across Jack Nicholson’s profile as smoke from his cigarette drifts up to mix with Faye Dunaway’s medusa-like hair in the eerie art nouveau poster for Chinatown by Diener/Hauser/Bates. “Forget it Jake, it’s Chinatown!” concludes the film, a lapidary payoff like Scarlett O’Hara’s famous statement, “After all, tomorrow is another day.”

The social and political strains of World War II and the postwar decade are reflected in the melancholy film noirs of the 1940s and 1950s. It’s no coincidence that Chinatown was made at the same turbulent time period as Vietnam’s final years, Watergate’s scandalous precipice and Nixon’s terrible second term as president. By setting itself in Los Angeles in 1937, the film retains its freshness, vibrancy, and timelessness, and it deals with the controversies of that age, those related to the intricate politics of water in the parched west.

Gittes (Nicholson) is dragged into a world of municipal corruption, sexual transgression, and the power of old money while collecting divorce proof on behalf of a suspicious wife. Noah Cross (John Huston) and Evelyn Mulwray (Faye Dunaway), the estranged daughter of a wealthy, vicious industrialist, are introduced to him. Evelyn’s husband, the head of the Los Angeles Water and Power Board, has mysteriously died.

The first of Robert Towne’s two recurring metaphors in the screenplay is water itself. Someone has been pumping water out of local reservoirs during a severe drought, and it becomes evident that land speculators are manipulating this most precious of human resources for their own benefit. “Water flowed uphill to get the money,” as the old Western adage goes. Evelyn Mulwray’s husband, Hollis Mulwray, bears a striking resemblance to William Mullholland. As a self-righteous plutocrat who has manipulated the deluge to further his own interests, Noah Cross evokes the endearing Old Testament patriarch played by John Huston in the 1966 hit The Bible.

Outsiders tend to either ignore or misinterpret Chinatown, which illustrates the futility of good intentions when used as a metaphor. Jake worked as a police officer in Chinatown during his time in the LAPD, and he returns there at the end of the film in a futile attempt to redeem himself. Every scene has him in it, and he’s almost always in view of the camera. Every frame is composed by Polanski, and he dictates every camera movement. We see everything through his eyes.

An intense summer heat wave is depicted in the cityscape, where the dazzling exteriors distort perception, while the stray rays of light that filter through the venetian blinds create a frightening atmosphere. Strings and percussion are used to create suspense, while a distant, bluesy trumpet is used to create evocative, introspective settings. Nicholson’s Gittes stands out as a smug, self-assured character who eventually loses his social footing and ends up like the cliché drowning man grasping for a life preserver.

Sources: https://www.lunchbox-productions.com

Categori: Entertaiment