These aren’t the first films to deal with the subject of mental illness, but they are among the greatest. A star goes CRAZY in these stunning films.

- 7 Best Movies About Lewis And Clark That You Should Watching Update 07/2024

- 17 Movies About Black People That You Need Watching Update 07/2024

- 10 Green Haired Anime Characters That You Should Know Update 07/2024

- 5 Best Shows Like Tabletop That You Should Watching Update 07/2024

- 10 Best Psychic Anime Characters That You Should Know Update 07/2024

Empathy may be one of film’s greatest strengths. It is possible for a well-crafted film to get us to care passionately for bizarre fictitious characters and their issues in under two hours thanks to such an immersive medium. Audiences can relate to and empathize with nearly any protagonist with just a little help from quality cinematography and passionate acting.

You Are Watching: 15 Best Movies About Crazy People That You Should Watching Update 07/2024

When the protagonist we’re viewing through isn’t the most trustworthy narrator, what do we do then? Many filmmakers have used the unique power of film to elicit empathy for atypical characters, particularly those who are declining in their mental health. Each of these films manages to express something unique about mental illness by placing us in the shoes of a character on the verge of sanity. These are a few of the best movies about humans going berserk.

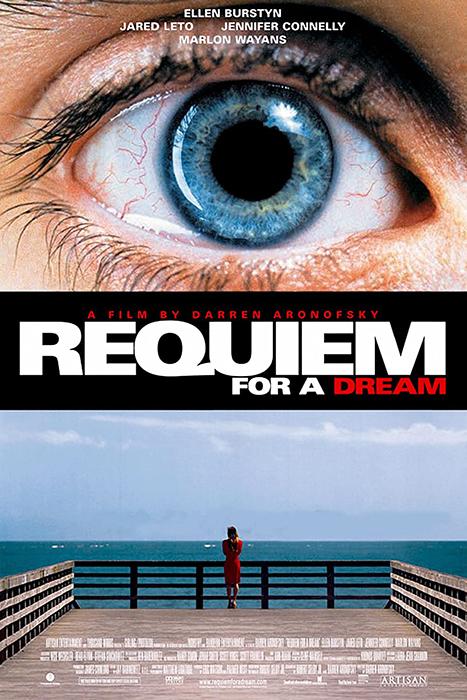

1. Requiem for a Dream

Even though Requiem for a Dream is one of the most emotionally draining films ever made, its most memorable portion is a woman’s relationship with her fridge. Sara Goldfarb, played by Ellen Burstyn, is an elderly widow who spends most of her time watching infomercials and game programs on television.

Sara gets tricked into thinking she’ll be going on her favorite game show after all thanks to a fictitious phone call, so she goes on a tight diet to prepare. The fridge appears to be growling at her when she is alone, so she can’t resist. Sara is prescribed amphetamine weight loss pills by an unscrupulous doctor as she waits for an event that will never arrive. As her illness continues to develop and she is taken to a psychiatric facility, she has delusions and is subjected to electroconvulsive therapy. As the film comes to a finish, Sara, eagerly anticipating her upcoming appearance on television, falls into a near-vegetative state, providing one of the most memorable and heartbreaking scenes in modern film history.

2. The Shining

Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining is a ghost story sans ghosts for the majority of its running period. Instead, we get a glimpse into the mundane lives of the emotionally detached Torrance family as they work to keep the Overlook Hotel warm over the long winter months. In spite of her husband Jack’s violent outbursts and her son Danny’s psychic visions and greater dependency on communication through an imaginary friend called “Tony,” fragile matriarch Wendy attempts to keep things together.

Things get out of hand when the family’s mental health begins to deteriorate, or maybe it’s just a side effect of that. This time it is Wendy (the “horror movie fanatic” mentioned previously) who sees most of the apparition as she fleeing from the newly-murdered husband in the third act.

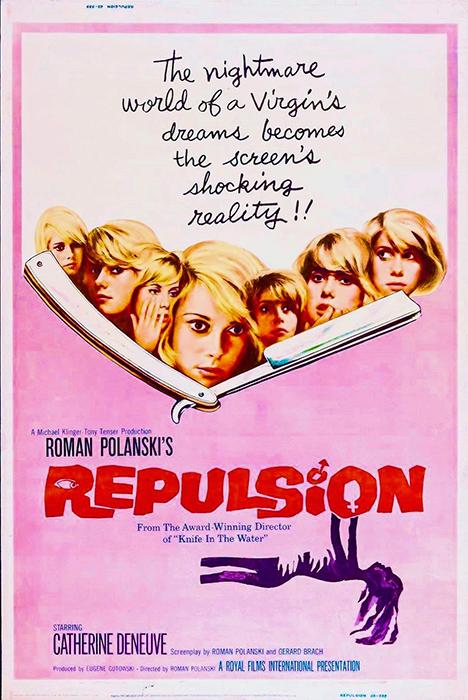

3. Repulsion

Debilitating and eventually violent paranoia gripped Belgian manicurist Carol in the psychological horror thriller Repulsion (Catherine Deneuve). Her good looks don’t mask the fact that she’s shy among guys and bothered by the noises of her sister having sex in their shared flat.

Carol’s deteriorating psychosis is exacerbated when her sister leaves for a trip, leaving her stranded in the apartment. It’s clear that she was sexually abused at some point in her life, and Roman Polanski’s haunting black-and-white visuals of groping hands appearing from the walls make her apprehensive of intimacy. In the end, her neurotic suspicion of the men who appear to view her simply as a sexual object evolves to deadly wrath..

4. The Tenant

Repulsion, Polanski’s third film in his “Apartment Trilogy,” which also contains Rosemary’s Baby and Repulsion, is both hilarious and terrifying at the same time. Polanski plays Trelkovsky, a frightened young man who enters into a Paris apartment where the last occupant took his life. His new landlord and neighbors are constantly berating him for having guests around at night, which causes him to develop a sexual relationship with a former tenant’s buddy.

Trelkovsky’s descent into psychosis is so gradual that it’s hard to tell when his perspective becomes untrustworthy in this basically plotless picture. All eyes are on him, as if to prepare him for a suicide attempt like the last tenant’s. The cafe that served her meals is now feeding him, and the neighbors across the courtyard are keeping binoculars trained on him. However, the cryptic conclusion to the film does little except reinforce the notions of being stuck in a life that isn’t your own and unable to communicate anything other than an incessant, and swiftly ignored, cry for assistance.

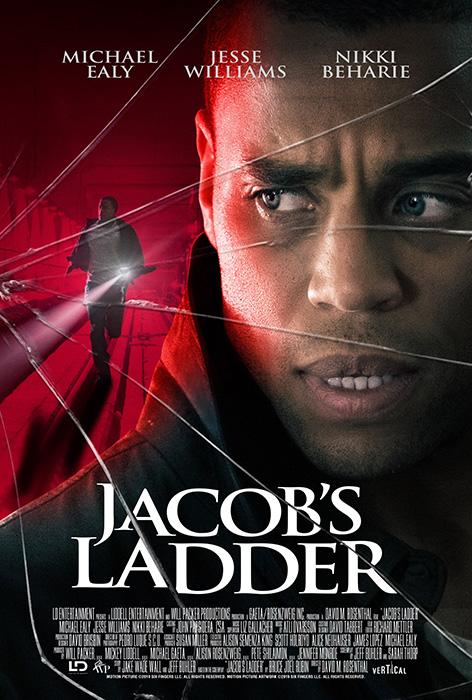

5. Jacob’s Ladder

Ex-soldier Jacob Singer (Tim Robbins) is haunted by memories of his time in the Vietnam War while living in 1970s New York City as an ordinary citizen. Horrors are not restricted to his recollections; they are found in an abandoned subway station he discovers, the faceless figures lurking in shadow, and fleeting contacts he has with his son, who was murdered in an accident several years earlier. Is this just a severe case of PTSD, or is there something else going on?

A combination of Jacob’s delusions and a chance encounter with some of his old unit mates leads him to believe in a plot involving a government-sponsored study of an aggressiveness-inducing substance. It takes Jacob a long time to realize and accept what has happened to him after seeing images of hell and a hospital full of decay. Until then, though, filmmaker Adrian Lyne has his spectators sifting through clues like Jacob, trying to differentiate fact from fantasy.

6. Black Swan

When it comes to psychological thrillers, Darren Aronofsky knows how to get the best out of a ballet dancer prepared to perform in Swan Lake in his hands. Natalie Portman has made her decision. It’s not long until Nina’s fragile state is exacerbated by her desire to perform flawlessly in front of an audience and her jealousy of new dancer Lily.

As Nina begins to put enormous strain on herself, she sees a shadowy doppelganger chasing her, discovers mysterious scratch marks on her back, and tries to remove a hangnail that just keeps peeling off her finger.

Black Swan is more than just a ballet since it depicts the physical and mental toll that an ambitious artist takes in his pursuit of excellence.

7. The Babadook

Great horror movies have monsters that are both frightening and symbolic. The Babadook, a film about a mother’s struggle to raise her son Samuel after the death of her husband, surely falls into this category. On her son’s bookshelf, she finds a copy of the titular children’s book and reads about the top-hatted Mr. Babadook, who torments those who reject its existence.

After a string of bizarre events, sleep deprivation turns Samuel against his mother and Amelia against her own son, both of whom place the blame on the Babadook. It is her inability to acknowledge the Babadook that renders her vulnerable to being possessed by it, and she comes dangerously close to injuring or even killing her kid before regaining her composure. Finally, the Babadook is tamed, which is likely to be a metaphor for the loss of loved ones, as well as grief, death, and a whole lot more.

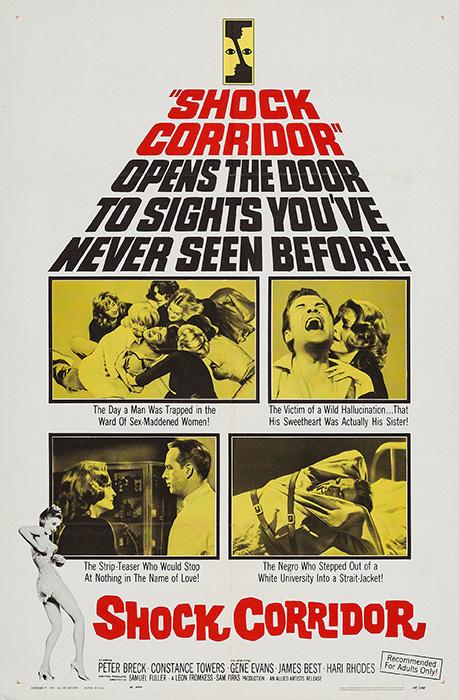

8. Shock Corridor

With the help of an undercover journalist, filmmaker Samuel Fuller’s Shock Corridor explores the minds of those driven insane by political circumstances. An incestuous relationship between Johnny Barrett and his “sister,” who is actually his girlfriend posing as such, is the key to solving a well-publicized murder, so he checks himself into the mental hospital where it occurred.

A former soldier who was brainwashed into believing he’s the Confederate general during the Korean War, a nuclear scientist who went back to his childhood after seeing the consequences of his work, and a black man motivated by prejudice into believing that he is a member of the Ku Klux Klan, are the three main patients with whom he speaks during his investigation. Barrett discovers the name of the killer through interviews with these victims of social evils, but only after his mind has been irrevocably damaged as a result of his stint in the facility.

9. Session 9

Session 9, a film about an asbestos abatement crew’s mission to clean up an abandoned mental hospital, is scarier than its visuals. Dissociative identity disorder patient interviews are found on session tapes soon after they begin their study.

As one of the crew members goes missing and Gordon, the team’s leader, plays through the session tapes leading up to the last, titular session 9, tensions and discomfort rise among the members of the group. As time passes, it becomes evident that the patient’s most vicious alter ego, “Simon,” is still lurking in these deserted corridors. As a haunting, the setting’s tragic past is combined with someone’s poor mental state to bring about new harm.

10. Take Shelter

As a result of being so believable, Jeff Nichols’ take on insanity is a little more subdued. Curtis, a husband and father played by Michael Shannon, begins to have unsettling visions of an imminent natural disaster. In truth, his mother’s paranoid schizophrenia first appeared when she was approximately the same age as Curtis is now, and only he and his wife are vividly aware of his family’s history of mental illness.

Read More : 12 Types Of Anime Characters That You Should Know Update 07/2024

In spite of this, Curtis begins to put his livelihood at risk by borrowing tools to build a shelter from the storm he has seen, and he also puts his family at risk by being so erratic and dedicated to following his visions. Take Shelter also has a cliffhanger ending, but it’s appropriate for a movie about the uncertainty that comes with dealing with a mental illness in the real world.

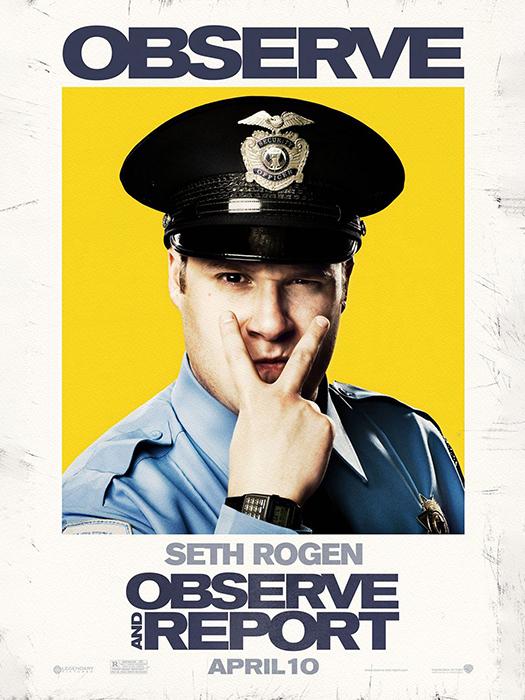

11. Observe and Report

“Paul Blart: Mall Cop 2” was published at the height of Seth Rogen’s comedic success, and was marketed as a sequel to “Paul Blart: Mall Cop.” There were mixed reviews and poor box office returns for this key film in Rogen’s career, presumably because it was less of a madcap adventure and more of a suburban black comedy remake of Taxi Driver.

To portray Ronnie, a manic-depressive mall officer with a hunger for power that intensifies with his deteriorating mental health, Rogen gives his all.

He fails the psychological exam to become a police officer and instead tries to kill the bad man and win the lady—in this example, the bad guy being a mall flasher and the girl being a vacuous makeup counter employee with whom Ronnie is infatuated—by doing so.

12. Antichrist

There is no room in Antichrist for the faint of heart. Willem Dafoe and Charlotte Gainsbourg star in the film about an unknown couple (Willem Dafoe and Charlotte Gainbourg) whose baby kid sneaks through an open window as they are having sex. It’s her husband’s error to treat her himself with a trip to a secluded forest cabin since she feels guilty for his death and sinks into sadness. When she has manic and increasingly violent episodes, she demands sex as a means of escaping her pain, and he intends to remain celibate.

One of Lars von Trier’s most harrowing films, Antichrist offers a harrowing look at a chaotic world through the perspective of a depressed person, as the filmmaker acknowledged he was while revising the script when his executive producer disclosed its original ending.

13. Barton Fink

Barton Fink’s focus on writer’s block and how it affects “the life of the mind” may be due to the Coen brothers’ experience with writer’s block in another film they were working on at the time (which would become Miller’s Crossing).

When Barton Fink (John Turturro) moves to 1940s Hollywood with the intention of writing socially-aware movies to make a difference, that mind belongs to Fink himself. The strange noises in his little hotel room and the surface-level working class milieu of his new neighbor Charlie (John Goodman, at his best), however, keep him locked on the first line of a “wrestling picture.” instead. In Barton Fink, which was heavily influenced by Polanski films like Repulsion and The Tenant, nothing is clear, but that just adds to the complexity of its isolated protagonist’s mental state.

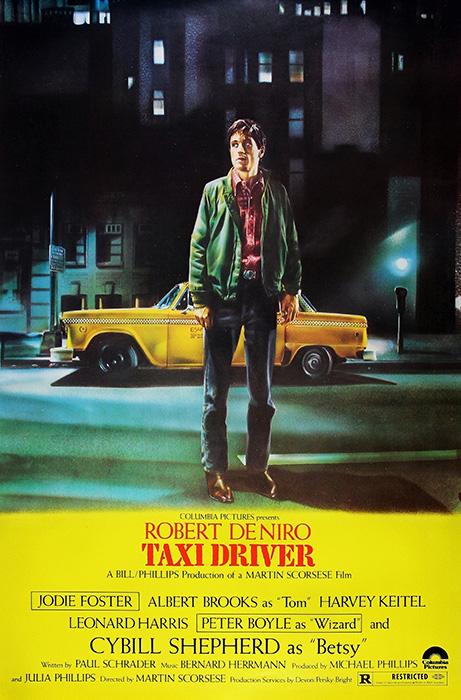

14. Taxi Driver

One of the best portraits of a man going insane in cinema, Martin Scorsese’s picture of a lonely Vietnam veteran living as a cab driver in the New York slums. Although he is charming in the beginning, Robert De Niro’s portrayal of the shy Travis Bickle quickly turns creepy when the actor insists on taking a date to the pornographic theater where he spends most of his spare time. To put it another way, Travis’s emotional solitude and ideas of manly heroism—again, to kill the bad people and save the girl—led him to violent dreams of clearing out the “scum” of society.

Some have speculated that the final scene may have taken place only in Travis’s head because of the film’s tonally discordant ending, but a more disturbing interpretation is that society will sanction his violent tendencies as long as they’re committed against communists abroad or members of the criminal underclass at home.

15. Eraserhead

As with Antichrist, Eraserhead may represent a view of the current world as experienced by someone who suffers from acute, severe anxiety, just like Antichrist. In a tiny apartment building in a desolate industrial wasteland, a man (played stonefacedly by Lynch regular Jack Nance) finds himself the inadvertent father and sole guardian of a mutant child who does nothing but howl in pain day after day in David Lynch’s debut feature.

Sources: https://www.lunchbox-productions.com

Categori: Entertaiment