Among the best movies about the North and South Poles, you’ll find sub-zero risk, adventure, and shapeshifting monsters.

- 13 Best Funny Shows Like The Office That You Should Watching Update 04/2024

- 10 Anime Characters Outfits That You Should Know Update 04/2024

- 10 Best Shows Like Siesta Key That You Need Watching Update 04/2024

- 10 Best Movies About The 70s That You Should Watching Update 04/2024

- Top 10 Anime Characters Sad That You Should Know Update 04/2024

Since a white Christmas in the UK is once again doubtful, the Royal Geographic Society in west London is the best bet for a photogenic facsimile heaped high on a soundstage on December 20. Charles Frend’s 1948 EalingStudios film Scott of the Antarctic will be screened at the prestigious Kensington location in London.

You Are Watching: 10 Best Movies About Antarctica That You Should Watching Update 04/2024

Huge for the studio, it would be a British debut for Technicolor and a major selling point for the legendaryJack Cardiff’s cinematography. Using video acquired by Herbert Pontingon during Captain Scott’s expedition in 1912, Cardiff and his crew transported heavy camera equipment across Swiss and Norwegian sites.

Keep up to date with the latest news from the BFI.

Receive BFI updates, including articles, videos, and podcasts.

Even though it was made before Scott’s reputation was re-evaluated, there’s a lot to enjoy in its depiction of upper lips that have been frozen firm. The film’s cinematic ambition may be clearly seen thanks to the latest restoration of this boy’s-own adventure tale of tragic, foolish grandeur.

There will be a question and answer session after the film with serial pole-botherer and Scott biographer Sir Ranulph Fiennes, who will be available to answer questions about the ill-fated expedition and perhaps even his own forays into filmmaking, most notably the 1967 dynamiting of Richard Fleischer’sDoctor Dolittleset.

We’ve compiled a list of ten additional films for people who can’t make it to the actual event but still want to experience it virtually. This list of films set in the Arctic and Antarctica is sure to keep you warm.

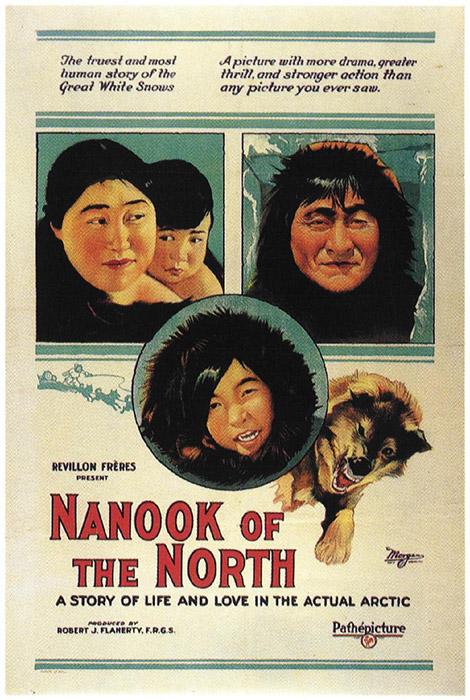

1. Nanook of the North (1922)

The extended shadow cast by doubts about the film’s authenticity has given Nanook of the North its problematic reputation as a starting point for ethical debates in documentary filmmaking. Robert Flaherty staged events and facilitated on-screen illusions, blurring objective truths for verisimilitude of effect, but the effect remains—a reconstruction of the lives of “Nanook (The Bear), his family, and little band of followers, ‘Itivimuits’ in Hopewell Sound, Northern Ungava” that never loses sight of humanity. With each breath-taking scene that follows, the ‘truth’ of the matter becomes progressively abstracted by the indifferent glare of a hostile terrain, synthesizing the struggles of the filmmaker and the protagonist.

2. The Great White Silence (1924)

When The Great White Silence footage from the 1950s was first shown at the London Film Festival in 2010, it was the result of a BFI restoration. Before it was reassembled into the more popularly viewed feature film 90 DegreesSouth(1933), the official document of Captain Scott’s fatal trip to the South Pole captured by self-taught filmmakerHerbert G. Ponting.

Read More : 10 Best Movies Like The Orphan That You Should Watching Update 04/2024

Early events, such as the Terra Nova’s confinement in the pack ice and the preparations for the fateful effort to reach the pole, may be seen with a sense of urgency thanks to the newly restored tint and HD master. However, even with Ponting’s camera, the footage he captured could only go so far; what begins with staged structures of Scott’s five-man crew concludes with images, minimal animation, and passages from the diary of Scott. A compelling early lesson in documentary storytelling, not merely a historical document.

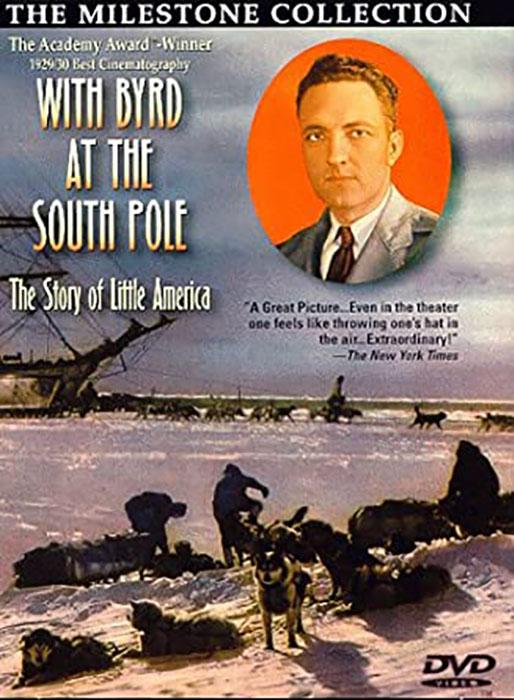

3. With Byrd at the South Pole (1930)

With the other true-life polar ventures on our list ending in disaster or failing, it seems we should include a more upbeat documentary portrayal of their journey. According to Richard E. Byrd’s flight log, he was the first pilot to fly across the South Pole in 1929, four years after completing the same expedition at the North Pole.

Joseph Rucker andWillard Van der Veera were sent by Paramount to chronicle Byrd’s attempt, and the film itself was funded by Paramount. After winning the Pulitzer Prize for his newspaper reporting, New York Times reporter Russell Owen went on to win his third Academy Award for cinematography in the following year.

4. Dirigible (1931)

The South Pole is calling my name! A few minutes into Frank Capra’sDirigible, Jack Holt makes a bold declaration: “Me and my gas bag!” Akin to his past films with the actor, Submarine (1928) and Flight (1929), Capra dips into his black book of US navy contacts in order to allow some remarkable flying escapades, maybe inspired by With Byrd at the South Pole.

It’s difficult to categorize Dirigible as either proto-blockbuster or military-tech propaganda in the pre-code era. A first calamity, in which the dirigible is brought down by an electrical storm, is enough to make up for the romantic parts on the ground, which feature an excellent pre-King KongFay Wray. When a plane crashes, Captain Oates-like heroics are on display as a wounded soldier crawls to death to save the lives of others.

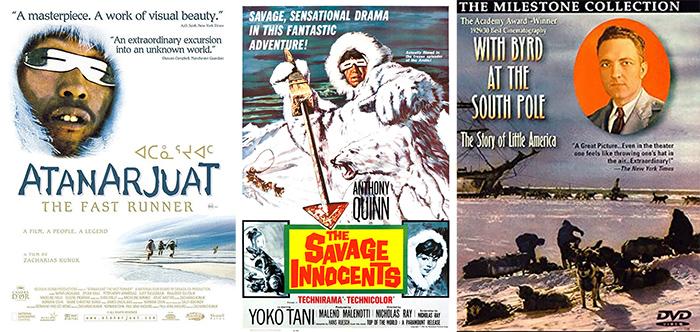

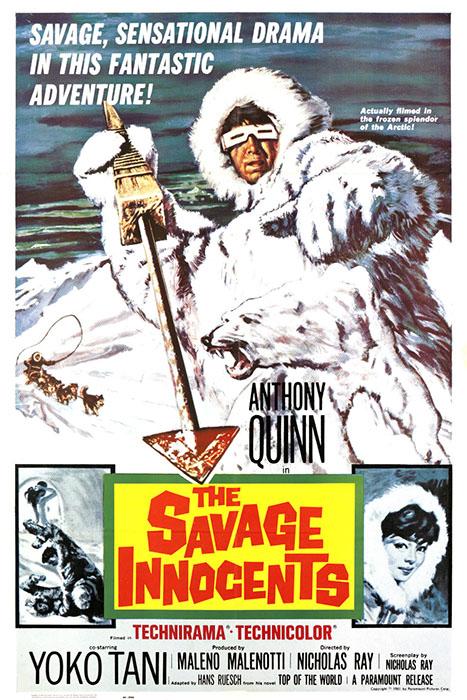

5. The Savage Innocents (1960)

The Savage Innocents, Nicholas Ray’s picture starring Hollywood’s all-purpose ethnic character actorAnthony Quinnas Bob Dylan’s favorite wife-swapping eskimo, makes obvious his debt to Flaherty early on. At times stunningly beautiful in its blend of studio and location photography, the picture has an artificial to it that supplants Nanook of the North’s supposedly subjective approach.

Because of the odd dubbing of Peter O’Toole, this film was shot on 70mm film and has widescreen compositions that pay tribute to John Ford and even Michelangelo Antonioni. It may not aim for Flaherty’s pseudo-realism, but it accomplishes something similarly profound with its wealth of ethnographic detail and Quinn’s career-best performance.

6. The Thing (1982)

If the painted backdrops and frequent process shots of some of the earlier films on our list don’t reveal their studio locales, chances are that the absence of clearly frozen breath beneath the halogen lighting will. By contrast to fellow survivor Childs (Kurt Russell), MacReady (Kurt Russell) seems to be puffing much more in John Carpenter’s great Antarctic thriller (Keith David).

Matthijs van Heijningen Jr.’s 2011 prequel to Christian Nyby’s (through Howard Hawks) take on theJohn Campbell Jrstory isn’t worthless of your time, either.

7. The Endurance: Shackleton’s Legendary Antarctic Expedition (2000)

Read More : 15 Best Comedy Anime That You Should Know Update 04/2024

The official record of Ernest Shackleton’s failed effort to reach the South Pole can be seen in the 1919 film South (also known as Endurance). Frank Hurley shot the film, and the sale of the film’s rights helped fund the trip. The James Caird’s 800-mile voyage to South Georgia, which Hurley’s film omitted, was the other half of Shackleton’s adventure.

Much of the material from South, up until the devastation of The Endurance, is used in George Butler’s gripping documentary. Reconstructions and conversations with the families of those who survived the trip bring the story to a close afterward. An remarkable feat of survival and naval courage is depicted, but it does not tell the complete narrative of Shackleton’s post-expedition failures and foolish restlessness that would ultimately to his death at the place of his greatest endeavor.

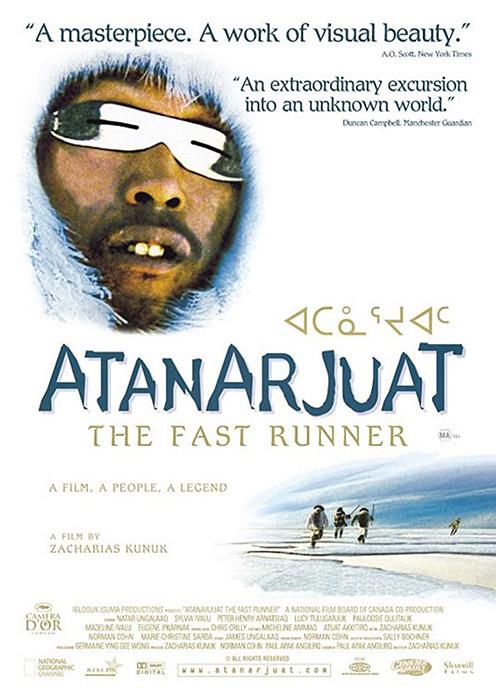

8. Atanarjuat – The Fast Runner (2001)

Zacharias Kunuk’sAtanarjuat – The Fast Runneris conceptually the polar opposite of The Savage Innocents. It returns to Flaherty’s subjectivity of focus. Here, in the first film shot almost entirely with digital cameras by Inuit actors and crew, a 1,000-year-old saga of Shakespearean proportions is brought to life.

Documentary filmmaking in its early phases doesn’t make any concessions to western audiences, but the classical narrative eventually takes hold and brings an epic breadth and heaviness to the proceedings. Events mirror the intimidating immensity of the environment while portraying a psychologically claustrophobic picture of a town at the end of the world, with murder, rape, patricide, expulsion and some very quick running.

9. Encounters at the End of the World (2007)

In Antarctica, what kind of individuals would I meet? “What were their hopes and aspirations?” McMurdo Station in Antarctica is the subject of Werner Herzog’s singularly inquisitive gaze, which he expresses uncommon disdain towards. More at ease with the volcanologists and hermetic penguin-counters out in the wild, he captures the frozen roof of a subglacial “cathedral” with greater proficiency.

He snarls, “I would never do another penguin movie.” “My questions about nature… were not the same as yours.” One penguin is obviously different from the others — the suicidal lunatic, on a different path than his Oscar-winning pals. Herzog’s penguins are no exception.

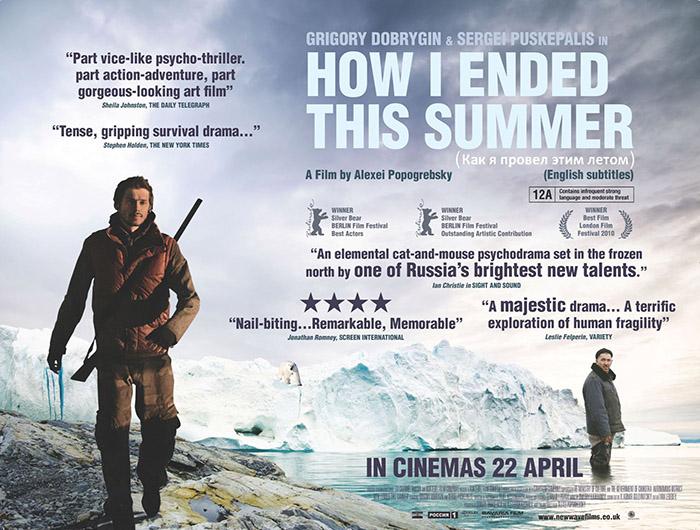

10. How I Ended This Summer (2010)

Relationships between the two main characters in How I Ended This Summer remain icy not only because of the frigid climate of northern Siberia. As the pair’s contact breaks down and a game of cat and mouse commences, what begins as an experiment in isolation and psychological brinkmanship quickly turns violent.

Aleksei Popogrebsky, the Russian filmmaker who won the best feature award at the London Film Festival in 2010 for his superb Arctic thriller, has gone silent since. In the latter stages, he brilliantly ratchets up the tension, but never loses sight of the countryside. There is more than enough comic relief to go around, even if he never quite gets around to resolving the unanswered questions at the end of the film’s runtime.

The Blu-ray and DVD versions of Scott of the Antarctic are now available. A grant from Studiocanal’s Unlocking Film Heritage program helped pay for Scott of the Antarctic’s digital restoration (awarding funds from the NationalLottery).

Sources: https://www.lunchbox-productions.com

Categori: Entertaiment