Even if Netflix doesn’t have HBO Max’s monopoly on Studio Ghibli, the streaming service’s anime movie choices are still worth checking out if you haven’t already signed up for a Crunchyroll membership. Lupin III, for example, is a great example of how Netflix has made it possible to appreciate a wide variety of mecha and even Miyazaki (thanks, Lupin III!). For the most part, the company’s move into anime has been a success, despite the company’s investment in its own films.

- 8 Best Shows Like Miami Vice That You Need Watching Update 04/2024

- 14 Best Shows Like Rick And Morty That You Should Watching Update 04/2024

- 20 Best Outdoor Movies That You Should Watching Update 04/2024

- 15 Best TV Shows Like PLL That You Should Watching Update 04/2024

- 10 Best Movies About Crime That You Should Watching Update 04/2024

If you’ve finished watching JoJo’s Bizarre Adventure or Demon Slayer on Netflix, there are still plenty other anime movies to watch. Our list of the top 10 Netflix anime movies includes classics, anthologies, and Originals, as well as lesser-known titles. There is a lot of turnover in the streaming library, especially when it comes to anime films, however this list has been updated as of July 2021.

You Are Watching: 10 Best Anime Movies On Netflix That You Should Watching Update 04/2024

The following are the 10 best anime films currently streaming on Netflix:

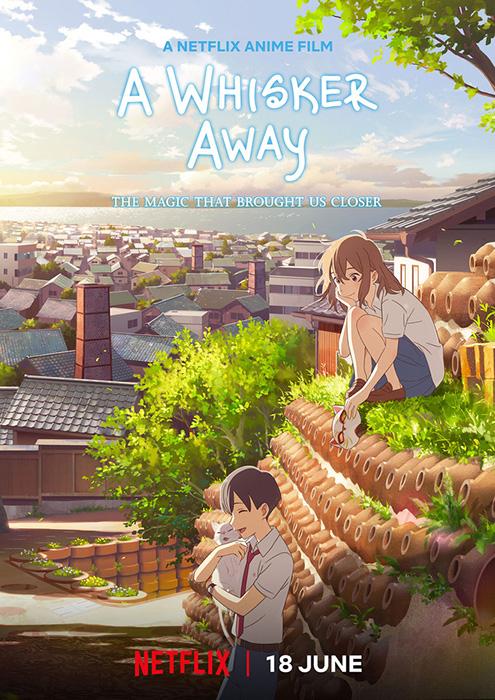

10. A Whisker Away

There have been creepier things done in movies than miraculously changing into a cat in order to get closer to your crush, but those are few and far between in the world of film. It’s a little more complicated than just putting a boombox outside a window. A Whisker Away, by directors Junichi Sato and Tomotaka Shibayama, is no exception to this rule. With its angsty middle schoolers and crinkly toy tunnels, Mari Okada’s writing successfully leapt the animation through some emotional loops, before landing its goofy premise in emotional honesty. Miyazaki’s canon of magic (a fat face-dealing cat and a full cat-world) is well-integrated with some honest dives into the mental health difficulties of its protagonists (not quite as deeply and darkly as Neon Genesis Evangelion, but with a similarly stylish flair). Even if some of the characters can be a little unpleasant when first meeting them (they’re just middle schoolers, after all), their truthfulness shines through, and we’re impressed by the realistic animal animation and stunning pictures of Tokoname life. —Josh Oller

9. Modest Heroes

There are few better examples of boundary-pushing visual narrative in animation than short film anthologies. What one needs to do is take a quick look at anime anthologies from the past 30 years: It’s no exaggeration to say that anthologies are a vital part of anime history, not only because of their ability to introduce new and exciting talent, but also because of their role in preserving the legacy of anime’s past. Anime anthologies include Labyrinth Tales (1987), Memories (1995), and Animatrix (2003 American-Japanese co-production). Studio Ponoc’s first short film, Modest Heroes, follows in the footsteps of previous prestige anime anthologies like Howl’s Moving Castle and The Tale of Princess Kaguya by bringing together Hiromasa Yonebayashi, Yoshiyuki Momose, and Akihiko Yamashita to create a new chapter in the storied tradition of anime anthologies. Hiromasa Yonebayashi’s “Kanini & Kanino” is the anthology’s first and most clearly “Ghibli-esque” short. Yonebayashi’s directorial debut, 2010’s The Secret World of Arrietty, might be seen as a prequel to this short, which tells the story of a pair of anthropomorphic crab children living at the bottom of a riverbed. Yoshiyuki Momose’s second short, “Modest Heroes,” is the heartfelt centerpiece of the anthology’s second volume. “Life Ain’t Gonna Lose” depicts the story of a young woman and her son, Shun, who was born with a severe egg allergy but is otherwise a happy and normal child. Even if “Life Ain’t Gonna Lose” sets a very high bar for what’s to come, “Invisible” manages to match and even surpass it. Howl’s Moving Castle director Akihiko Yamashita, who also worked on Yasuhiro Imagawa’s Giant Robo: The Day the Earth Stood, was in charge of the project. Nevertheless, “Invisible” tells the story of a man who is plagued with a malady that makes him virtually invisible to everyone he encounters in his daily life. With this collection of short films, Studio Ponoc has delivered a strong follow-up to its debut effort, and Modest Heroes embodies the phrase popularized by Rod Serling: “…there is nothing mightier than the meek.” In the words of Toussaint Egan

8. Mary and the Witch’s Flower

When a child is eager to help around the house but ends up making more of a mess than they clean, it’s distressing. In Hiromasa Yonebayashi’s Mary and the Witch’s Flower, Mary is the protagonist. For the sake of Charlotte’s housekeeper and her great-aunt, Lynda Baron (Lynda Baron), she is unable to remove an empty teacup from Charlotte without dumping it on the floor. I don’t know what to say about this youngster. It’s almost heartbreaking. Just when it seemed like there was nothing to keep her occupied, two cats led her to a cluster of dazzling blue flowers, which immediately piqued her interest. Assuming she doesn’t know what the flowers are, Mary brings them back to Charlotte’s and discovers that they give anybody who touches them temporary magical powers. Starting at that point is where Mary and the Witch’s Flower begins its story—and it’s quite the story! A flying sentient broom transports Mary to a school for witches where she meets Madame Mumblechook (Kate Winslet) and Doctor Dee (Jim Broadbent), two teachers who put on a kind facade to hide their true motives. Mary and the Witch’s Flower has a familiarity to it as a narrative: From Studio Ghibli-lite Harry Potter to Studio Ghibli-lite Studio Ghibli with a sprinkle of Yonebayashi’s prior themes. As a whole, it is vivacious, soft and attractive. Every time we look for magic in the world around us, we’re met with disappointment. Art, and possibly especially animation, has magic and life in it, as evidenced by movies like these. In the words of Andy Crump:

7. Lu Over the Wall

The distributor GKids promotes Lu Over the Wall as a “family friendly” alternative to the usual computer-animated fare found in modern multiplexes, and that’s exactly what it is. There’s a difference between “whimsical” and “strange,” and Masaaki Yuasa’s Lu Over the Wall quickly crosses the line into the latter before the opening credits have even rolled. Very little time passes in which reality is even vaguely identifiable. Even the smallest clues of relatable features that stimulate our empathy are exaggerated, warped, and turned nearly unrecognizably by the process of dramatic exaggeration. This is a movie that doesn’t take itself too seriously, and that’s a good thing for the average moviegoer. The plot is both simple and complex: It’s not unusual for adolescent guys like Kai (played by Michael Sinterniklaas in the English dub) to hide out in their rooms and avoid the outside world, but Kai is no exception. Lu (Christine Marie Cabanos), a manic pixie dream mermaid crafted in tiny, joins Kai as he battles his own loneliness. What can a lone emo boy do in a fish-out-of-water story with xenophobic overtones? What are his options? It’s impossible to count how many upbeat musical interludes there are in Lu Over the Wall. Using the term “creative” to describe the picture is an insult to the film’s ingenious craziness. In the words of Andy Crump:

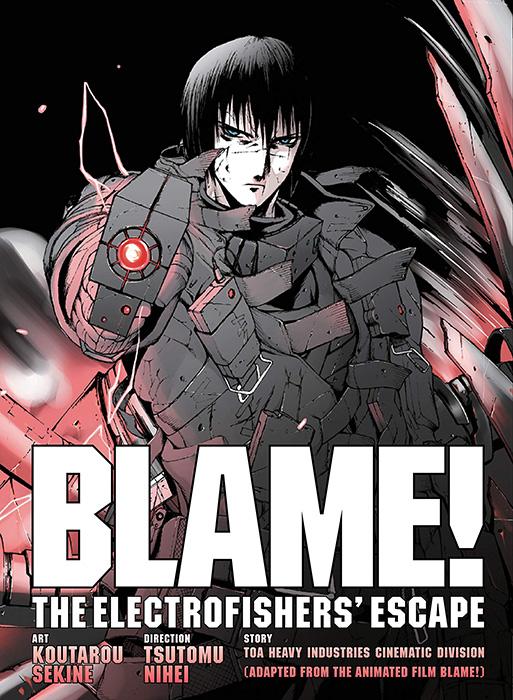

6. Blame!

He’s a visionary in the dark industrial sci-fi genre. Before becoming a manga creator, Nihei was trained as an architect, and his work is marked by a singular fascination with the creation of new environments. Ghoulish and bow-legged synthoids fill the Byzantine factories with gothic accents, armed with bone-swords and gristle-shooters. In addition to Blame!, Nihei’s aesthetic legacy includes videogames, music, and even art and fashion, all of which have been influenced by his work. Anime adaptations of the series have been attempted in the past, but none have proved successful. Until now, that is. Hiroyuki Seshita of Polygon Pictures has finally released the long-awaited Blame! film with the help of Netflix. Taking place in the distant future, where an enormous, self-replicating superstructure known as The City has taken over the planet, Blame! centers on the lonesome adventures of Killy, a reclusive outsider on a quest to find a human with the “net terminal gene,” an elusive trait thought to be the only way to stop the city’s unending hostile expansion. While the manga’s early chapters are condensed and simplified in the film, Sadayuki Murai’s script and Nihei himself supervise the film’s narrative and action-driven approach. Nihei’s distinctive look is faithfully reproduced by Hiroshi Takiguchi and Yuki Moriyama, while the characters are given distinct, clearly recognizable features and silhouettes that substantially enhance the story’s comprehension, making it easier to follow. In terms of faithfulness to the manga, Blame! is a perfect introduction to the series. Blame! makes a solid case for being one of, if not the greatest, original anime films to visit Netflix in a long time, as well as one of the most creatively fascinating. Theodore Egan

5. Lupin III: The Castle of Cagliostro

Miyazaki’s body of work is brimming with treasures, each film in its own right a part of the canon that is the anime tradition. Even those films that could be deemed his “worst,” in terms of their visual storytelling and emotional virtuosity, receive so much praise that they nevertheless stand head and shoulders above those animators who just aspire to his stature. Lupin III: The Castle of Cagliostro is a good example of this type of story. When it comes to Kazuhiko Kato, Miyazaki has taken on the infamous master criminal and made what can be considered one of his less-successful flicks. Miyazaki’s infancy as a director is evident in Castle of Cagliostro, which suffers from a sluggish middle section and a basic adversary, yet nevertheless manages to shine through the weight of a preceding work. It was widely derided by fans for removing Lupin’s anarchic tendencies and instead portraying him as a gentleman thief who steals only when he feels like it. In any event, Miyazaki’s pre-Ghibli masterpiece, The Castle of Cagliostro, remains a vital and essential relic. Regardless of its flaws, a Miyazaki picture is a success. Jason DeMarco and Toussaint Egan

4. The End of Evangelion

Episodes 7 and 8 are among the most talked-about in the series’ fanbase. Ikari’s self-loathing and hatred plagued him throughout the story, so the two-part finale, “Do you love me?” and “Take care of yourself,” was a departure from the show’s central conflict, instead taking place in Shinji’s subconscious as he tried to overcome the self-loathing and hatred he felt throughout the story’s duration. Disgruntled fans threatened Anno’s life and vandalized Gainax’s building with graffiti because of this conclusion’s unconventionality and disappointing character. For his reaction, Anno began working on a two-part ending to the series that would be aired in theaters instead of online. When it comes to endings, End of Evangelion isn’t what you’re searching for. As a result, the viewers were given one of the most savagely bleak, avant-garde, and life-affirming anime series finales ever seen. For the most part, it’s a combination of the finest and worst of everything that Evangelion has to offer. Although the film’s title refers to the pleasure of rebirth, End of Evangelion keeps loyal to its subtitle’s ethos. Theodore Egan

3. A Silent Voice

It is refreshing to see Naoko Yamada’s presence in a medium that is typically constrained by the primacy of masculine aesthetic sensibilities and saturated with hypersexualized depictions of women commonly labeled as “fan service,” to say nothing of the incomparable quality of her films.. Yamada is a masterful director, capable of capturing attention and evoking melancholy and bittersweet catharsis through delicate compositions of deft sound, swift editing, ephemeral color palettes, and characters with rich inner lives rife with knotty, relatable struggles through delicate compositions of deft sound, swift editing, ephemeral color palettes, and characters with rich inner lives rife with knotty, relatable struggles In A Silent Voice, based on Yoshitoki Oima’s manga of the same name, all of these senses are at work. In elementary school, Shoya Ishida bullies Shoko Nishimiya, a deaf transfer student, to the entertainment of his peers. As soon as Shoya goes too far and forces Shoko to move yet again out of worry for her safety, he is shunned and becomes a pariah among his friends. Shoya and Shoko meet as teenagers and Shoya tries to make apologies for the trauma he did on her, all the while struggling to comprehend his own motivations. One of the best films of the year, A Silent Voice is a moving depiction of adolescent abuse, reconciliation and forgiveness. Theodore Egan

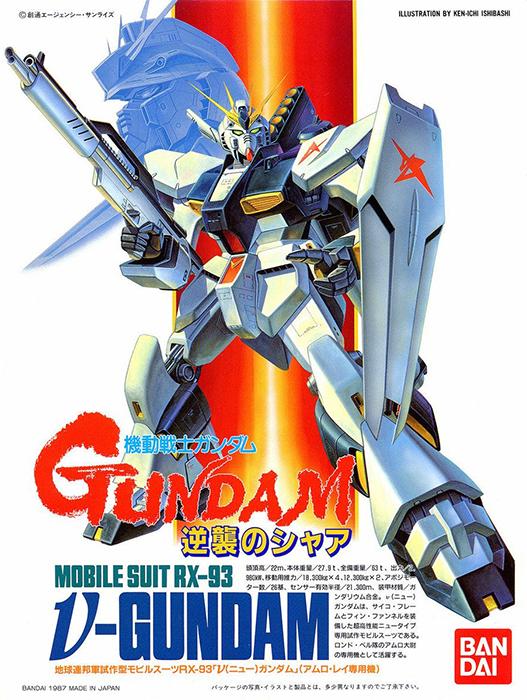

2. Mobile Suit Gundam: Char’s Counterattack

“Universal Century Timeline” of Mobile Suit Gundam TV series, Char’s Counterattack is the first Gundam theatrical film and last chapter in the original epic that began in 1979 with the “Universal Century Timeline”. The film was directed and written by Gundam inventor Yoshiyuki Tomino, who properly adapted his novel Hi-Streamer for the screen. As one of the best Gundam films, Char’s Counterattack is excellent at bringing the 14-year feud between Amuro Ray and Char Aznable to a close. Char’s Neo-Zeon forces attempt to hurl a nuclear-armed asteroid onto Earth in an attempt to rescue the colonies from their adversaries, the Earth Federation, but instead they kill everyone on the planet. When it comes to Gundam stories, Tomino takes a hard sci-fi approach, explaining how things like enormous mobile suits and “newtypes” work in detail (humans that have evolved to acquire psychic abilities). Char and Amuro’s animosities and enmities are thoughtfully explained by Tomino, who prevents the viewer from picking a clear winner. When it comes to discussing war’s horrors and how humanity, despite its many accomplishments, can’t manage to shake its baser tendencies, the Gundam series has never shied away. Amuro vs. Char’s Counterattack tries to do the same thing, although it’s primarily focused on finishing up the rivalry between the two characters. One of the best Gundam films ever made, the picture has stunning space battles, a terrific soundtrack, and some of the most renowned designs in the franchise’s long history. One drawback is that if you haven’t invested in these characters for hundreds of episodes of television, the plot can be confused and Char/finale Amuro’s may not connect as powerfully. In any case, Char’s Counterattack is still a must-see moment in the Gundam universe, nearly 30 years after its release. Welcome to the land of the Rising Sun! —J.D.

1. Mirai

Almost all of Mamoru Hosoda’s original films from the last decade are experiments in autobiography in some form or another. For the most part, Summer War’s story revolved around the story of Hosoda seeing his wife’s family for the first time, a story that was rehashed from his 2000 directorial debut Digimon Adventure: Our War Game!. Hosoda’s mother’s death in 2012 inspired Wolf Children, which was in part motivated by Hosoda’s own fears and dreams about becoming a parent. The Boy and the Beast, which was released in 2015, was inspired by Hosoda’s personal doubts about the proper role a father should play in his son’s life. His first-born son encountering his infant sibling for the first time inspired Mirai, Hosoda’s sixth film, rather than the director’s own personal experiences. In the wake of his sister Mirai’s birth, Kun, a toddler, feels displaced and insecure. Mirai, a magnificent fantasy adventure, whisks the audience through Kun’s whole family tree, concluding in a heartbreaking conclusion that stresses the beauty of what it means to love and be loved. It is Hosoda’s best work, the first non-Studio Ghibli anime film to be nominated for an Academy Award, and an experience that is both educational and enjoyable.—

Sources: https://www.lunchbox-productions.com

Categori: Anime