As A Clockwork Orange is re-released, we order the director’s oeuvre from 1951’s Day of the Fight to 1999’s Eyes Wide Shut.

- 15 Best Rome Movies That You Should Watching Update 07/2024

- 15 Best Anime Websites That You Should Know Update 07/2024

- 10 Best B Movies Of All Time That You Should Watching Update 07/2024

- 20 Similar Movies Similar To Disturbia Update 07/2024

- 10 Best Shows Like Young And Hungry On Netflix Update 07/2024

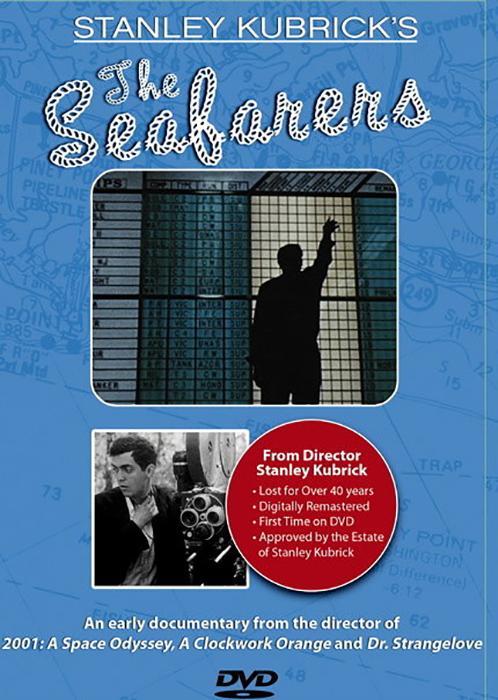

16. The Seafarers (1953)

The Seafarers International Union commissioned a half-hour short film. Although there is some value in the observational aspects of this movie, it is really a long commercial/propaganda piece for the union’s facilities and bargaining strength.

15. Fear and Desire (1953)

First feature film Stanley Kubrick repudiated and tried to prevent anyone from seeing it, even after the copyright had expired. No, I don’t think so. It’s not great. It does, however, exhibit Kubrick’s ability to control the camera and his interest in war as a theme, so it’s not entirely a waste of time and money.

14. Flying Padre (1951)

Day of the Fight was Kubrick’s first speculative newsreel story, and he followed it up with a 10-minute documentary on a priest who flew his two-seater plane over his massive New Mexico parish. There are some great aerial shots and an incredible high-speed reverse track on the padre as he stands next to his plane at the end of the film.

13. Spartacus (1960)

It was only a week into filming when Kirk Douglas’s star-producer sacked Anthony Mann as director and replaced him with Stanley Kubrick. A ponderous, pompous epic that never manages to generate the pace it demands even with the immediately iconic “I’m Spartacus” sequence with Kubrick acting as a Hollywood hireling, this is by far the least personal of Kubrick’s films:

12. Killer’s Kiss (1955)

Having failed with Fear and Desire, Kubrick tried again with a much more marketable offering: a film about a washed-up boxer and the dancer he falls in love with. This time, Kubrick was successful. This film is held back by bad performances and a shaky narrative structure. However, it accomplishes its purpose and sets Kubrick on his course.

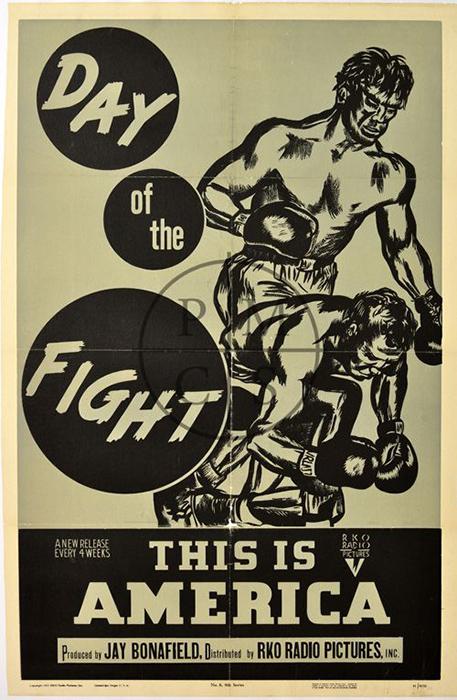

11. Day of the Fight (1951)

What an incredible experience for a first-timer. In 1950, Kubrick was just 21 years old when he shot this boxing biopic of Walter Cartier. Small but perfect, it ranks above some of his later works; Kubrick intelligently incorporated it into Killer’s Kiss and you can see its DNA in Martin Scorsese’s Raging Bull.

10. Eyes Wide Shut (1999)

It was a sour way to end one’s life. This final film by Stanley Kubrick appears to be an unimpressive sociosexual paranoia study despite the heavyweight cast and muscular directing, which makes it seem like a headswimmingly barmy portrayal of the risks of tampering with the upper echelons of power. Kubrick’s fondness for female nudity, even though Nicole Kidman plays one of his few important female roles, is shamelessly revealed in this film; as male-gaze cinema, this is an example.

9. The Killing (1956)

With this entertaining racetrack heist film that features a mosaic of flashbacks, rewinds, and jump-forwards, Kubrick followed up Killer’s Kiss with an avant-garde polish. The Asphalt Jungle, which shares its topline name, Sterling Hayden, isn’t all that different from this film. Kubrick’s exquisite, fluid camerawork is beginning to influence the direction of future films, signaling the way forward.

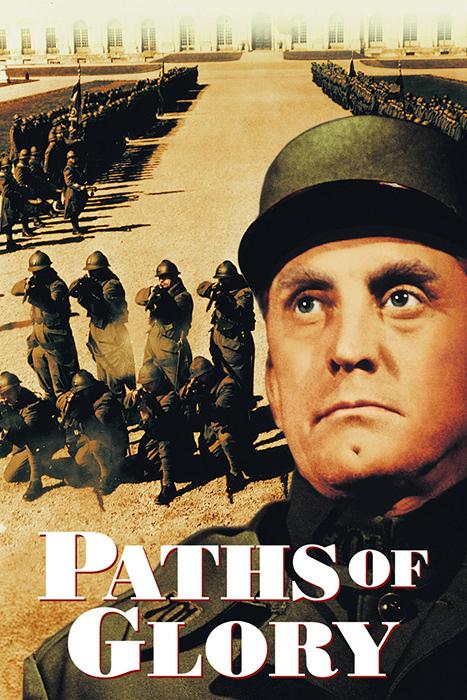

8. Paths of Glory (1957)

Late in his career, Kubrick was all about progression: each project was a step up from the one before it, and so on. It was Kubrick’s first foray into major-studio drama after proving his mettle in the genre. As expected, he appears at ease in this film’s big moral topics, which he tackles with clarity, though not the nuance he’d reach in later works. With his distinctive long reverse tracking shots accompanying Douglas through the trenches and a masterfully staged execution scene, Kubrick is also beginning to establish his directorial style.

7. Lolita (1962)

Eyes Wide Shut is Kubrick’s most troublesome film, even more so than that of the director. No matter how you slice it, a black comedy about a paedophile rapist will not go unchecked, no matter how revered the source material is. Nevertheless, it is a watershed moment in Kubrick’s career as a filmmaker. For example, I had no idea he was funny. Nothing in his prior professional experience suggested as much. It was a brilliant move to cast Peter Sellers in one of those multi-role roles popularized by Ealing comedies, because Sellers’ s subtle humour perfectly balances the film’s underbelly.

6. The Shining (1980)

Read More : 20 Best Shows Like Dharma And Greg That You Should Watching Update 07/2024

The genre shift was a statement in and of itself by the year 1980, when Kubrick had nothing left to prove. He wanted a big office blockbuster regardless of his austere reputation, and after Barry Lyndon’s flop, he went with the chilling tale of Stephen King instead. The Shining is effective because Kubrick gradually increases the creep factor while still getting outstanding performances from his stars. Jack Nicholson is as mesmerizingly heavy-lidded as he ever was, and Shelley Duvall, who was treated with contempt by Kubrick during the shoot, achieves an amazing level of desperation in the film. Everybody from the Coen brothers to Ari Aster has taken note of Kubrick’s use of elevator blood waves and live maze models in the film.

5. Full Metal Jacket (1987)

As he became preoccupied with other endeavors, Kubrick’s production dwindled in the 1980s. By the time this gruesome Vietnam War film hit theaters, Oliver Stone’s Platoon, which had been released a year earlier, had surpassed and eclipsed it. To its credit, R Lee Ermey’s never-ending stream of innovative foulmouthed profanity was thoughtfully incorporated. Training and combat in the film are depicted in the film’s diptych format as equal sources of stress, with the most frightening moments occurring at the film’s conclusion in either half. With its use of the Beckton gas works and hundreds of palm palms imported from Thailand, Full Metal Jacket has the visual scope of Coppola and Cimino’s Vietnam films, but Kubrick’s film nevertheless has a significant impact on the viewer.

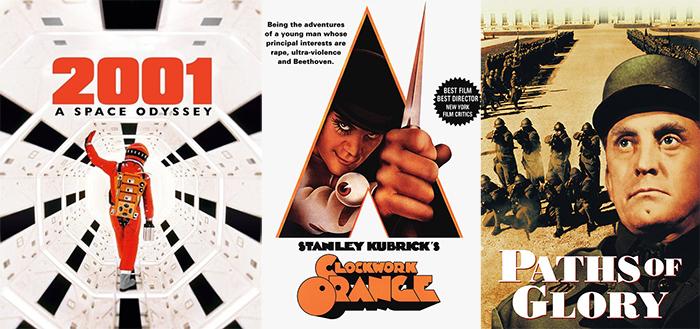

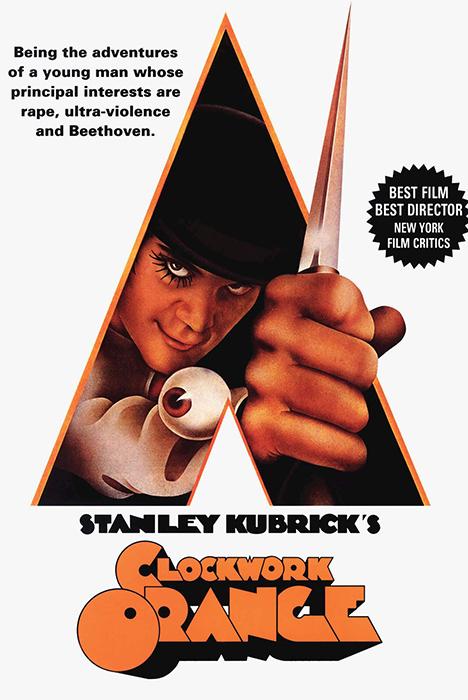

4. A Clockwork Orange (1971)

He unleashed this huge howl of wrath in the 1970s, a fiery, belligerent rant as different from 2001’s eulogy to cosmic peace. At one point, Kubrick’s film takes aim at those in power because they can’t handle the difficulties they face, switching from quasi-fascist social control to excessively liberal liberalism. If you’re looking for a good time, you’ll find it in the first half of this picture, which is similar to Full Metal Jacket in that it’s where the action takes place. But what a show they put on!

3. Barry Lyndon (1975)

When comparing Barry Lyndon to A Clockwork Orange, how would you describe them? Barry Lyndon has to be the best of both worlds, though. Again, Kubrick reversed genres to contribute to the stately drama of literature. Although Kubrick was criticized for hiring Ryan O’Neal as his movie star, the dust has settled and O’Neal has emerged as the perfect, impenetrable cover for Redmond Barry, a shady social climber in the film. Barry and Marisa Berenson’s Lady Lyndon dance to Schubert’s Trio No. 2 as Kubrick pushes the technical envelope, employing Nasa lenses for the candlelit card game scenes and taking his passion for choreographing action to classical pieces to maybe its most intense level. The film Barry Lyndon is truly a masterpiece.

2. Dr Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (1964)

For a Peter Sellers comedy, this is among the greats: a superb attack on the United States’s Cold War attitude, bolstered by a Sellers multiple-character tour de force. With Trump in the White House, Full Metal Jacket-like Kubrick’s film is even more terrifying because there is no Merkin Muffley to stand up for dignity in the face of military violence. Kubrick crafts an instant classic in Slim Pickens’ bomb trip to oblivion but the climactic nuclear blast montage, with Vera Lynn warbling on the soundtrack, is a coup de cinéma of the greatest order—and practically impossible to top.

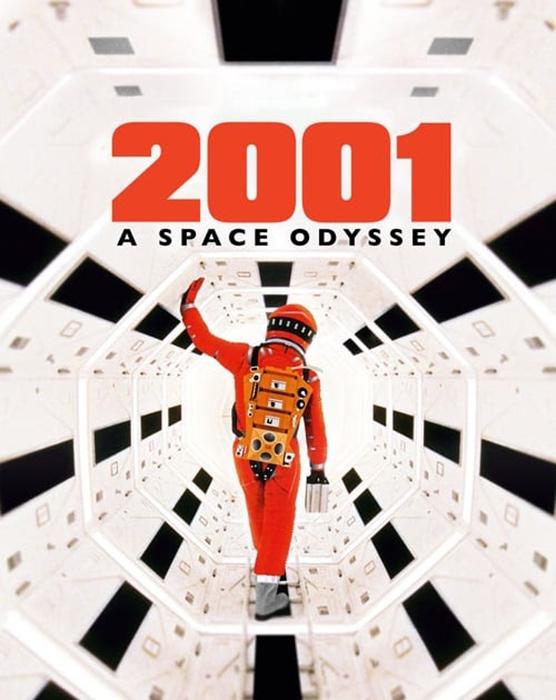

1. 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968)

The pinnacle of Stanley Kubrick’s oeuvre. This film’s spaceship docking sequences, sung to The Blue Danube, after the inspired thrown bone match cut, are well-known for their mesmerizing brilliance. Even with developments in CGI and visual effects, no film sequence has dated less. No current film-maker has the intellectual fortitude to attempt anything like this. Among the many reasons why 2001 is considered one of the greatest films ever made is its ambition, the near-perfect craftsmanship of its craft, and the profusion of unexpected little joys — Leonard Rossiter’s slimy Russian scientist is always flabbergasting. Nothing else in cinema has come close to Kubrick’s vision for this film: the evolution of human awareness. Astoundingly impressive work.

Sources: https://www.lunchbox-productions.com

Categori: Entertaiment