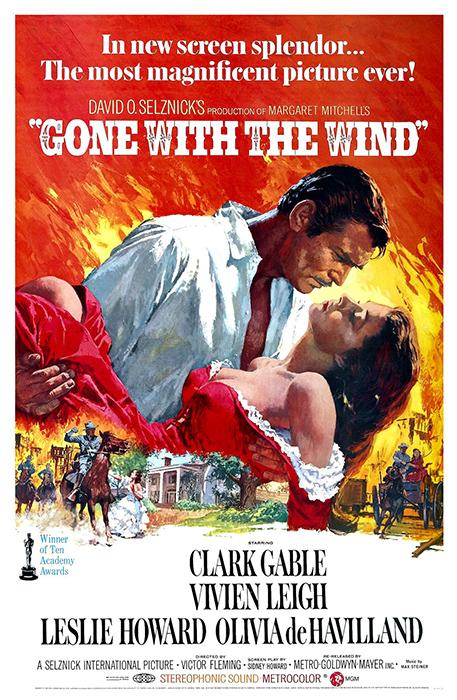

In celebration of the return to theaters in 4K digital restoration of the epic civil war romance Gone with the Wind, we’ve compiled a list of ten further films set in the Deep South worth seeing.

- 15 Best Movies Like Interstellar That You Should Watching Update 07/2024

- 9 Best Saw Movies That You Should Watching Update 07/2024

- 13 Best Fate Grand Order Anime Characters That You Should Watching Update 07/2024

- 10 Best CGI Anime Movies That You Should Know Update 07/2024

- 10 Best Shows Like Broad City That You Should Watching Update 07/2024

1. Gone with the Wind (1939)

There has been a long-standing fascination among filmmakers with Southern ambiance and imagery that stretches back to films like The Birth of a Nation (1915) and Beasts of the Southern Wild (2012). Because they were among the first to join the union, the states that make up the heart of the area — South Carolina, Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, and Louisiana – hold a special place in the hearts of Americans everywhere. Films set in the Deep South address questions of race and segregation, freedom, home, violence, and destiny in a terrain that is at times both fetid and transcendent.

Some of the most ridiculous and cruel stereotypes and caricatures of the Deep South have been depicted on the big screen. Many have equated it with “rednecks,” “buckteeth,” “hookworm,” and “trailer trash” because of its reputation as a conservative and traditional state. However, the epic narrative and historical specificity that the Deep South has to offer attract the majority of filmmakers.

In the UK, you can see each of these recommendations.

Gone with the Wind (1939), which will be re-released in 4K digital restoration next week, is the pinnacle of this feat. David O. Selznick’s acclaimed epic, set in 19th-century Georgia, is a timeless cinematic monument of the Deep South: a tragic and passionate view of the changes brought about by the American Civil War. Vivien Leigh and Clark Gable, as the tenacious Southern belle Scarlett O’Hara and the dapper gentleman Rhett Butler, personify the essence of the region.

Gone with the Wind is one of the best examples of cinematic soul cuisine, but here are 10 side dishes that really evoke the heat and sweep of the South.

2. A Streetcar Named Desire (1951)

While the film’s influence may be seen in The Simpsons, Seinfeld and Woody Allen’s Blue Jasmine (Blue Jasmine 2013), the most significant shift in the portrayal of sex and violence on the American screen can be traced back to A Streetcar Named Desire. Elia Kazan had to concede to a morally redeeming ending when adapting Tennessee Williams’ Pulitzer Prize-winning drama from the stage. Kazan fought against the Hollywood Production Code in order to keep the precedent-setting rape scene.

As Blanche (Vivien Leigh), a fading Southern beauty who is forced to move in with her obnoxious sister Stella (Kim Hunter) and her obnoxious husband Stanley (James Caan), the film is set in the filthy, cramped slum of New Orleans (Marlon Brando). In one of cinema’s greatest ensemble pieces, Leigh and Brando, both of whom were schooled in distinct styles of acting (Leigh in British theatre, Brando was fully established in Method), both reach the emotional peak.

3. Carmen Jones (1954)

George Bizet’s 19th century opera Carmen, staged by Otto Preminger, features the talents of black actors who were previously overlooked in Hollywood. In her role as the seductive title character, Dorothy Dandridge made history as the first African-American woman to be nominated for an Academy Award for Best Actress.

Read More : 10 Best Movies About DMT That You Should Watching Update 07/2024

Although it begins and ends in North Carolina, the most memorable song and dance moments take place in Louisiana. Singing songs by Oscar Hammerstein II such as “Stand Up And Fight” or “Beat Out That Rhythm Of The Drum” pulse with an exuberant energy that perfectly suits the film’s bright Technicolor and lively production design.

4. The Long, Hot Summer (1958)

Paul Newman is the quintessential star of the Deep South. It was in Martin Ritt’s version of William Faulkner’s The Long Hot Summer that “Blue Eyes” first came to popularity. Later, Ritt directed Cat on a Hot Tin Roof (1958) and Sweet Bird of Youth (1962), as well as two more films, Hombre (1963) and Hombre II (1964). (1967). Not even Marlon Brando could have done a better job in such a high-pressure situation of balancing bravado with restraint than Robert De Niro.

Rugged outlaw Ben Quick (Newman) is suspected of setting fire to several barns in the small Mississippi town of Frenchman’s Bend, where he meets the wholesome daughter of the town’s magnate, Clara (Joanne Woodward) (Orson Welles). Newman and Woodward’s raunchy verbal sparring, captured in breathtaking CinemaScope with the steamy lenses of Joseph LaShelle and later married, raises the temperature even further.

5. The Fugitive Kind (1960)

This is the second film in which Tennessee Williams and Marlon Brando collaborated. As opposed to A Streetcar Named Desire, Sidney Lumet’s adaptation of Orpheus Descending keeps things simmering rather than boiling. After fleeing New Orleans, Brando is hired by Anna Magnani, the owner of a small-town five-and-dime, to work there (winner of the Oscar for best actress in 1955 for another Williams Deep South melodrama, The Rose Tattoo).

The Fugitive Kind is a gloomy and doggedly attuned to the sweltering and poisonous climate of the Deep South, despite the fact that Lumet’s best films tend to be set in New York. The haunting temptations of the characters’ inner lives are tied to the landscape with innumerable erotically-charged close-ups, obsessively garish lighting cues, and exquisite tracking views in a location that is at once natural and expressionist.

6. In the Heat of the Night (1967)

Norman Jewison’s In the Heat of the Night depicts a ramshackle tiny town in Mississippi in 1967, where racial prejudice is still alive and well, not just in the Deep South. A murder and the larger issue of race relations in America require streetwise Philadelphia homicide investigator Sidney Poitier to work with racist sheriff Rod Steiger.

Jewison created a greasy, disheveled atmosphere of murmuring discontent that reflected the uncertain mood of the time, as the Civil Rights movement took hold, even though the film was shot in Illinois. With five Oscars, including best picture and best actor for Steiger, the Academy was swayed by its morally vexing connection between Poitier and Steiger.

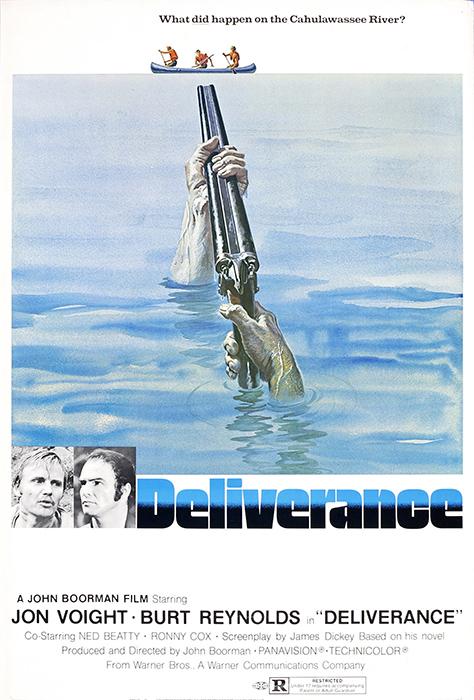

7. Deliverance (1972)

Deliverance, John Boorman’s adaptation of James Dickey’s novel, did nothing to improve the impressions of the Deep South, particularly Appalachia, which depicted the natives as bucktoothed, incestuous hillbillies. Its “squeal like a piggy”/”Dueling Banjos” reputation is considerably exceeded by this river journey about four city businessmen – led by Jon Voight and Burt Reynolds – who try to recreate the American frontier spirit.

Cinematographer Vilmos Zsigmond’s wide-open cinematography reveals the Chattooga River’s placidity and verdant woodlands as a breeding ground for murder and rape, not spiritual renewal. Deliverance is one of the greatest pictures about masculinity in the woods made by Boorman, who was given a 2013 BFI Fellowship.

8. Down by Law (1986)

Read More : 10 Best Anime Like A Silent Voice That You Should Watching Update 07/2024

In so many of the films on this list, the subject of strangers or outsiders intruding on a revered and cherished Southern way of life is a recurring one throughout the storylines set in the Deep South. His third picture Down by Law, a fantastical amalgamation of jail drama, neo-noir and quirky comedy, was quick to destroy these connotations in the spirit of a real maverick.

With three strangers (John Lurie, Tom Waits, and Roberto Benigni) placed in a New Orleans prison cell, they soon escape into the portentous surroundings of the Louisiana bayou, sharply photographed in black-and-white by cinematographer Robby Müller. The film’s title refers to the bayou’s ominous atmosphere. As first-time visitors to the muddy backwaters of Louisiana’s bayou country, Müller and Jarmusch provide viewers a fresh perspective on the characters who are all lost and alone in their environment.

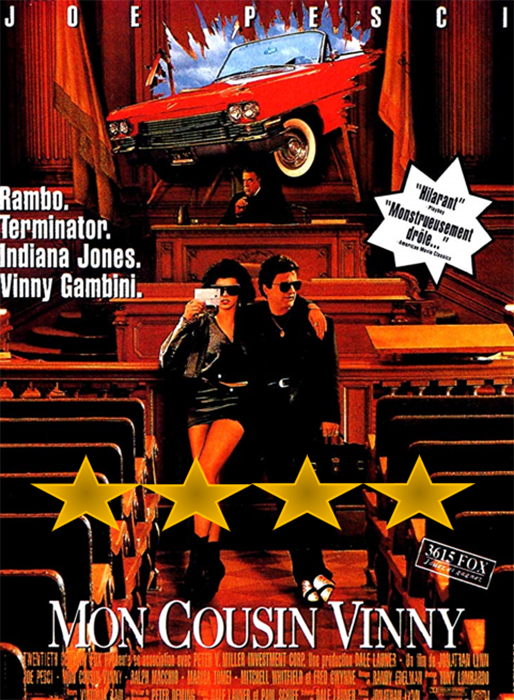

9. My Cousin Vinny (1992)

My Cousin Vinny may seem insignificant in the context of classic Deep South courtroom dramas like Inherit the Wind (1960), To Kill a Mockingbird (1962), and A Time to Kill (1965). (1996). While the film doesn’t have the hefty topics of its predecessors, it’s nonetheless an entertaining and imaginative farce that has a heartfelt appreciation for both the southern and northern groups.

An Oscar-nominated performance by Marisa Tomei as Joe Pesci’s sharp-tongued mechanic fiancée, the bumbling Brooklyn lawyer, is at his most endearing in this film about his cousin, who is being falsely convicted of murder. The courtroom scenes, directed by Cambridge Law graduate Jonathan Lynn, are not only riotously entertaining, but they also stake a claim to being some of the most realistic scenes ever captured on film.

10. Undertow (2004)

As a director, David Gordon Green has done an exceptional job of evoking the poetry and mythology of the Deep South. His first two films, George Washington (2000) and All the Real Girls (2003), though not true Deep South films, show an attention to nature and rural imagination that he brought to Georgia in Undertow. In this film, as in Terrence Malick’s previous work, we’re drawn into the characters’ inner lives by the beauty of the decaying Southern landscape.

Their evil Uncle (Josh Lucas), certain that their widowed father (Dermot Mulroney) is hiding some semi-mythical gold coins, comes to visit Chris (Jamie Bell) and Tim (Devon Alan), two brothers who live off the work of their hands on a run-down farmstead. Filmmaker David Gordon Green and regular cinematographer Tim Orr use a rusty, sun-refracted Deep South as the backdrop for this picaresque story, which is further enriched by handheld camerawork and on-location sound.

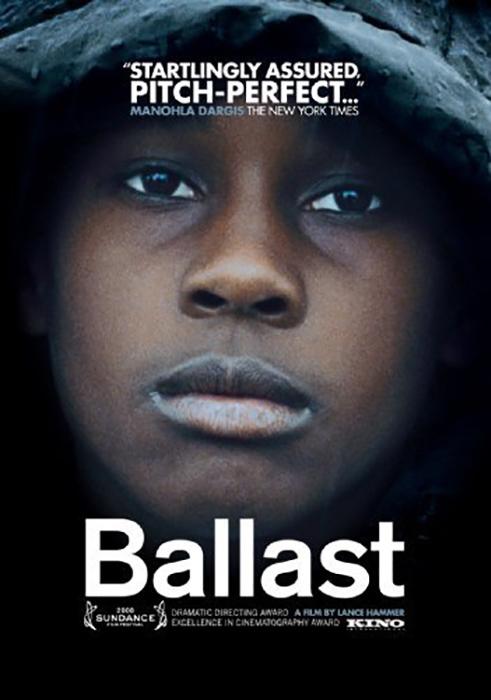

11. Ballast (2008)

Lance Hammer’s hardscrabble examination of fury and atonement evokes a harsh and lonely atmosphere thanks to the lugubrious watercolour sky of the Mississippi Delta. His brother’s depression, his grief, and his problematic 12-year-old kid are all affected by the death of one of the African-American twins. This is the most dignified dramatization of black poverty in America since Charles Burnett’s Killer of Sheep. It was shot on a low-budget with non-professional

12. Delta natives (1977)

Wintertime Delta’s cracks of quiet, empty gusts of wind, and boots crunching on snow form a soundtrack to the protagonists’ aspirations and desires. There are so many signs and portents all around the Deep South, but in Ballast they take on a more sparse and mysterious beauty.

Sources: https://www.lunchbox-productions.com

Categori: Entertaiment