It conjures up a world of on-screen permissiveness and depravity when you hear the term “pre-Code Hollywood.” In the early 1930s, before the sound era began, and before the censors stepped up their efforts to stifle the fun, this was the time period.

It’s actually one of the greatest misnomers in Hollywood history to refer to the pre-Code era as “pre-Code.” Will H. Hays’ introduction of the 1930 Code to govern the making of talking, synchronized, and silent motion pictures was the catalyst for all of the films produced during this fabled period. This was a list of “don’ts” and “be carefuls” demanded by various social and religious pressure groups to prevent cinema from corrupting Americanmorals.

You Are Watching: 10 Best Pre Code Movies That You Should Watching Update 07/2024

The BFI has the most recent news.

Receive BFI news, features and podcasts.

When it came to imposing themselves on studio executives during the Great Depression, early supporters of the Hays Code had a hard time getting their message across. Because of this, suggestions to tone down screenplays and cut potentially obscene passages were frequently ignored: thugs ran amok, corrupt politicians made hay, and wives and husbands alike succumbed to the enticements of decadent playboys and loosewomen.

Only after the Catholic Legion of Decency exerted pressure and the Production Code Administration was established in 1934 did Hollywood begin to be tamed. The golden age of Hollywood was put in motion by Joseph I. Breen, who oversaw the implementation of the Production Code. While the talkie revolution allowed filmmakers to tell it like it is, it also stifled frank discussion of the less-than-palatable aspects of daily life.

This list includes ten of the most popular works from the era when anything went.

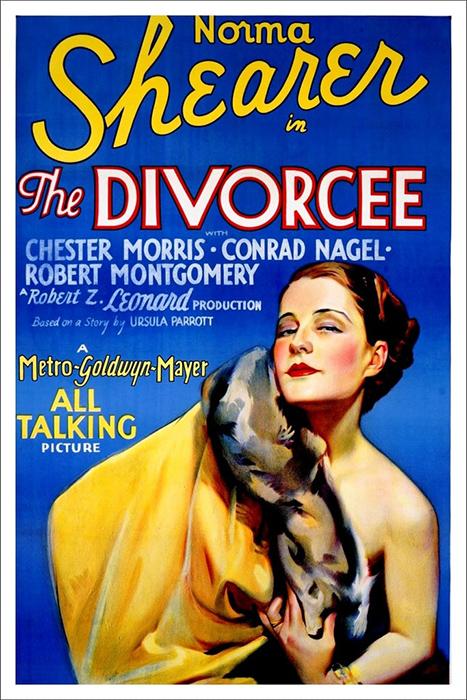

1. The Divorcee (1930)

Contrast Norma Shearer’s reaction to being cuckqueaned in this risqué stylish film with that of George Cukor’s The Women in order to understand the impact of the Production Code on Hollywood (1939). Hedonisticabandon and rape were Shearer’s fast revenge on her cheating husband (Chester Morris) in The Divorcee, although she remained silent at the end of the decade in The Divorcee.

When Irving G. Thalberg, who was Shearer’s wife and MGM’s chief creative officer, wanted Joan Crawford to star in this adaptation of an Ursula Parrott bestseller, the Hays Office refused to let the studio use its racy title, Ex Wife. In an effort to convince her husband that she was the right candidate, Shearer hired a photographer to take a series of sexy photos. Her performance in A Free Soul (1931) earned her a second Oscar nomination for best actress, proving once again that she could play a nasty girl.

2. The Sign of the Cross (1932)

It was Cecil B. DeMille’s trademark lurid immorality and sanctimonious sermonizing in the silent period that made him see the Code as a challenge rather than an impediment. Yet, while this adaptation of Wilson Barrett’s play contains such saucy moments as Poppea (Claudette Colbert) bathing in asses’ milk and Ancaria (Joyzelle Joyner) gyrating in the ‘Dance of the Naked Moon’, it’s the scenes of violence at the Circus Maximus that prove more provocative than even the orgies and the homosexuality. Garlanded nubiles are also threatened by alligators and gorillas, while elephants and tigers play with their victims in the arena.

Read More : 10 Best Anti Hero Anime Characters That You Should Watching Update 07/2024

When the film was rereleased in 1944, DeMille agreed to a 10-minute prologue comparing Nero (Charles Laughton in his Hollywood debut) and Adolf Hitler’s dictatorial barbarity. DeMille insisted that he had refused all requests to cut the more flagrant material, but he did make concessions when the film was reissued in 1944.

3. Three on a Match (1932)

This Mervyn LeRoy melodrama stars childhood friends Joan Blondell, Bette Davis, and Ann Dvorak in a sea of adultery, addiction, and kidnapping. However, the Hays Office gave it their full support because the villains (including a pre-fame Humphrey Bogart) were punished for their misdeeds.

Dvorak succeeds as the lawyer’s wife who pays the ultimate price for running off with gangster Lyle Talbot by being the last to light her cigarette with a single match. As a result, Dvorak’s career took a turn for the worse, and Blondell became the pre-Code poster girl instead of Davis. Following her time in Smarty (1932), Blondell starred in Gold Diggers of 1933, sang “Remember My Forgotten Man” in Gold Diggers of 1933, and refused the approaches of a corporate predator in Convention City (both 1933). This was the final one Jack L. Warner threw away when the Code was strengthened because he knew it would never be granted an exhibition certificate.

4. Red-Headed Woman (1932)

When it comes to Hollywood movies, homewreckers rarely do well, but Lil Andrews not only gets away with stealing Leila Hyams’ husband, but Chester Morris also refuses to press charges when she shoots him, and Lil flies off to Europe with chauffeur Charles Boyer to continue her gold-digging adventures.

Anita Loos was hired by Irving Thalberg to make it plain that Katherine Brush’s “wicked woman novelist” Katherine Brush relished her control over men and the ill-gotten money it brought her. By portraying Lil an over-the-top kittenish caricature who wields her blonde hair and delicate dresses as weapons in the struggle of the sexes, Loos was able to put Hays at ease. Clara Bow and Colleen Moore, as well as Barbara Stanwyck, Joan Crawford, and even Greta Garbo, were mentioned in casting dispatches. Thalberg, on the other hand, opted for Harlow, one of the era’s most gloriously impenitentvamps with Mae West.

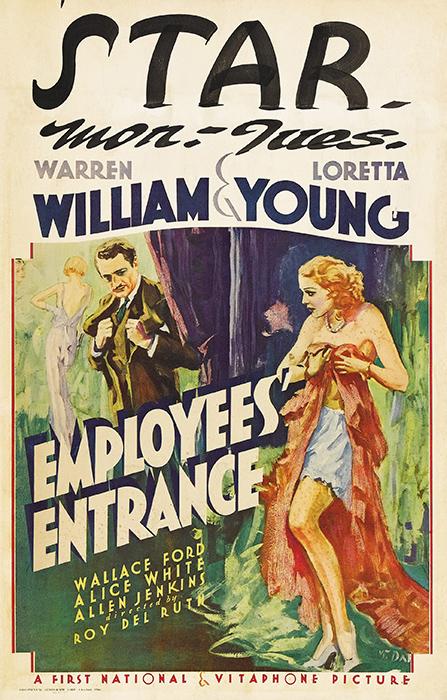

5. Employees’ Entrance (1933)

William Warren reprises his role as a womanizing banker from the earlier play Skyscraper Souls (1932), in which he played the pre-Code King. In this David Boehm adaptation, William plays the pre-Code King. After inheriting Edward G. Robinson’s role as Kurt Anderson in the role of the world’s largest department store, he exudes both casual cruelty and cynical charm. Within minutes after taking over, Martin West (Wallace Ford) and his shopgirl wife Madelene (Jennifer Garner) had their relationship shattered (Loretta Young).

Aside from Anderson’s use of Polly Dale (Alice White), the scene when he takes advantage of the sleeping Madelene has a particularly terrible echo in these #MeToo times. Her performance as the sexually free boss of Michael Curtiz’s Female is equally compelling (1933).

6. Murders in the Zoo (1933)

During the 1930s and ’30s, the majority of Hollywood’s film output consisted of everyday entertainments rather than Codebreakers. There were exceptions to this rule, such as Freaks (1932), King Kong (1933), and other gangster/monster films from Warners and Universal (1933). This dystopian Deco drama follows Paramount’s grisly Island of Lost Souls adaption with a tale of a big-game hunter’s jealousy over his trophywife.

To use his riches and rank, Eric Gorman (Lionel Atwill) leverages his power and wealth to punish those who dare to mingle with his provocative spouse, as Count Zaroff did in The Most Dangerous Game (1932). (Kathleen Burke). In the aftermath of a gruesome lip suture, Atwill also poisons a rival, forces Burke into an alligator pit, and unleashes a horde of climactic large cats. Although the zoophobic humor of Charles Ruggles is misinterpreted, this is nevertheless nasty.

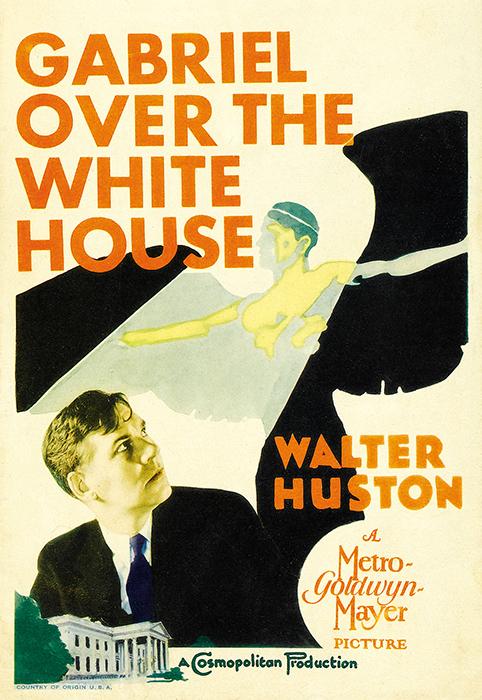

7. Gabriel over the White House (1933)

President Judson Hammond is a quasi-fascist who takes power in order to save America and the globe from its problems. It was just three years after his star turn in D.W. Griffith’s Abraham Lincoln (1930) that Walter Huston played this role. To show his support for newly inaugurated President Roosevelt, press baron William Randolph Hearst (who authored some of Hammond’s more demagogic lines) financed this adaptation of Thomas F. Tweed’s novel Rinehard, which may sound like a swamp-draining Trumpist nightmare.

MGM’s Louis B. Mayer, a devoted Republican, did all in his power to stall the story of a party stooge who becomes his own man after receiving a supernatural visitation from above. This results in the dissolution of Congress, the declaration of martial law, the summary execution of drug traffickers, and the use of force to compel Europe to repay its Great War debts. Astonished, the Hays Office released this brazen ode to authoritarianism with no alteration.

8. The Story of Temple Drake (1933)

In Safe in Hell (1931) and Virtue (1932), working girls Dorothy Mackaill and Carole Lombard have it difficult, but in this Southern Gothic epic that ranks among the most persistently gruesome films of the pre-Code era, none suffers quite like Miriam Hopkins. Following Ernst Lubitsch’s screwball classic Trouble in Paradise (1932), in which Hopkins exhibited a delectable amorality, in this bold adaptation of William Faulkner’s infamous novel Sanctuary, which the Hays Office had pronounced unfilmable, Hopkins slides into filth.

Rather than a fallen lady, Hopkins is more like a good-time girl who gets carried away on a night out with Jack La Rue, a violent mobster. Director Stephen Roberts uses disturbing close-ups and off-screen noises to illustrate her suffering, suggesting that she was involved in her own rape and subsequent descent into prostitution. The shock value has not diminished with time.

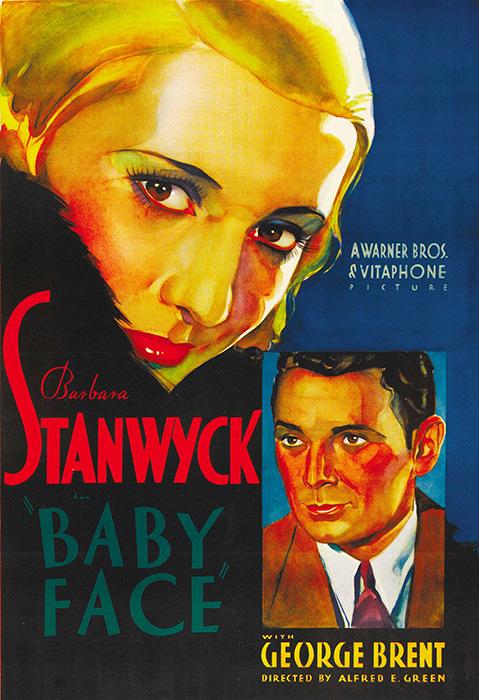

9. Baby Face (1933)

When Barbara Stanwyck appeared in Night Nurse (1931), Forbidden (1932), and Ladies They Talk About (1933), she embodied the pre-Code image of a self-sufficient woman in motion pictures. With the help of her pimping father, Lily Powers uses the tactics she learned at his filthy speakeasy to sleep her way to the top of one of New York’s most posh banks, making this Warner riposte to MGM’s Red-Headed Woman.

With the Legion of Decency shocked by its Nietzschean attitude to exploiting malleable men, as well as its depiction of Lily and Chico’s close friendship, the picture was based on a script that Daryl F. Zanuck and Stanwyck wrote together and sold for a dollar to the studio (Theresa Harris). In spite of its detractors among feminist critics, Baby Face hasn’t lost any of its impact or relevance.

10. Wild Boys of the Road (1933)

Pre-Code masterpieces like The Public Enemy (1931), in which James Cagney famously shoved a grapefruit into Mae Clarke’s face, were directed by William A. Wellman. Also, he made two of the most important social-realist tracts of the century, including this adaptation of Daniel Ahern’s novel ‘Desperate Youth’. Frankie Darro and Edwin Phillips, both high school dropouts, seek work at the height of the Great Depression in order to aid their suffering middle-class families. The episodic and frequently accusatory action describes their rail-riding exploits.

With its stated dedication to “problem films,” Warner had reservations about the sequence in which Phillips’ leg gets crushed by an incoming train. For Hooverville’s sewer pipe and city dump sequences, however, Wellman focused on the portrayal of everyday risks and living situations, so he cast genuine hobos in the roles.

Sources: https://www.lunchbox-productions.com

Categori: Entertaiment