The finest movies on Sundance Now tend to be those that you could have discovered on Netflix or Hulu before, outcasts and periphery classics combined with unmistakable current masterpieces. Lady Macbeth and Biggie & Tupac will only be available on Netflix, and no other streaming provider will feature them side by side. Sundance Now, like Fandor or MUBI, focuses on curatorial jewels rather than its vast archive (which is only, at last count, around 150 films). We’ve sifted through its repertoire and found the best independent films, documentaries, and more.

- 10 Best Anime Like Jujutsu Kaisen That You Should Watching Update 07/2024

- 20 Best English Anime That You Should Watching Update 07/2024

- 10 Cool Anime Characters That You Should Watching Update 07/2024

- 16 Best Samurai Movies That You Should Watching Update 07/2024

- 12 Best Occult Movies That You Should Watching Update 07/2024

Here are the 10 best movies streaming on Sundance Now:

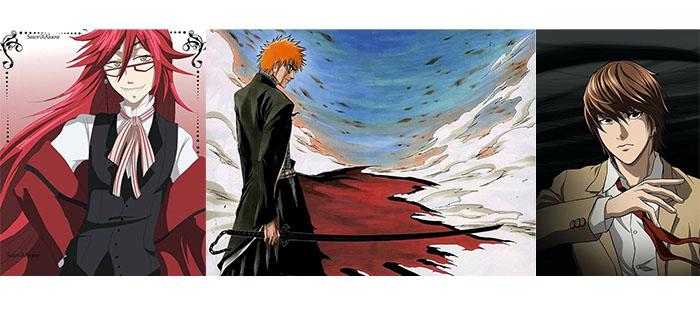

1. Biggie & Tupac

Biggie & Tupac, a documentary about the killings of musicians Notorious BIG and 2Pac, is a bizarre film from the start. A clipped cadence is used by Nick Broomfield in his narration and as the director of the film, suggesting that English is not his first language and Earth is not where he was born. While it is nearly incomprehensible that he is able to waddle his way into some of the most exclusive (and even terrifying) situations, one must remember that his weirdness probably makes him seem so non-threatening that the people who spill deeply incriminating confessions probably don’t think his footage will ever be released. Although Broomfield’s skepticism and questionable journalistic motives are evident throughout Biggie & Tupac, the film is nonetheless engrossing, despite the fact that it’s a far cry from a good investigation. A “bottom-feeding creep” has been used to describe Broomfield, and it isn’t hard to see how his techniques and outcomes could be viewed as the work of a person who is. When it comes to documentaries, does a man’s access to the subject matter justify the means? There are only 10 minutes left, but they’re worth the wait: an interview with Suge Knight (who the video quite obviously shows to be behind both killings) offers disturbing views on socioeconomic and racial realities. In the words of Dom Sinacola:

2. Cosmopolis

Apocalyptic takedown of unrepentant American capitalism, an almost word-for-word adaptation by David Cronenberg of Don DeLillo’s novel, Pattinson is aggressively deadpan as a young billionaire asset manager who relies on a world ruled by cosmic order and predictability in order to keep his head above water. When his new investments fail and stock takes a nosedive, the seams in his Patrick Bateman-on-downers schtick begin to unravel, showing him to be a painfully insecure youngster attempting to crawl back to some form of humanity, as he drives across New York to get a haircut. Pattinson rarely shows the character’s true nature, even in the midst of immense existential anguish, because his modus operandi is to maintain an image of self-control in the face of conflict. To put it another way, Pattinson’s extraordinary ability to convey an ocean’s buried neuroses through minor shifts in body language is what makes the piece so emotionally compelling. Those who predicted that Robert Pattinson’s presence in a Cronenberg film would wreck the film, it’s a delicious arthouse irony that his performance instead turned out to be the redeeming grace. —Oktay Ege Kozak

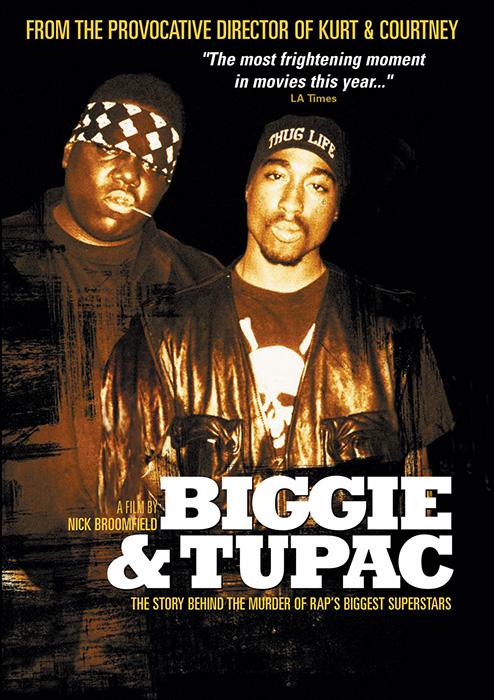

3. Boy

Read More : 10 Best Anime Abridged Series That You Should Watching Update 07/2024

When it was at its zenith, Taika Waititi’s second feature picture was the highest-grossing New Zealand film at the country’s box office. His writing and directing talent are at their best in this film. James Rolleston’s performance as a young boy searching for his identity and meaning provides the film its best chance of winning us over, while the filmmaking’s combination of tight comedy, realism in presenting a Maori society, and charmingly janky animation dress up its melancholy heart in colorful colors. If you’re a fan of Michael Jackson, you’ll probably love Boy as much as Boy does. Jacob Oller, author

4. Meek’s Cutoff

When it comes to reclaiming the Western for women, you can count on Kelly Reichardt. Western movies are often viewed as “male” affairs, though that’s an oversimplified critique that overlooks the impact women have had on Westerns both in front of and behind the camera; they are manly products about manly men doing manly things and pondering manly concepts. For example, in Meek’s Cutoff, Reichardt takes a stand against “bullshit macho posturing” by placing the guys on the sidelines (the only man here worth his salt is Stephen Meek [Bruce Greenwood], and even he is kind of an incompetent, entitled scumbag). Emily Tetherow, played by Michelle Williams, is the only one who can dispute his authority and take responsibility for the people in the caravan he has taken so far off the beaten track. Kelly Reichardt made Meek’s Cutoff, which is a stark, minimalist film. Her minimalist, simmering austerity is perfectly suited to the Western cinematic tastes. In the words of Andy Crump

5. Marjorie Prime

Marjorie Prime is a difficult film to categorize because of its mysterious nature. The character of the picture is best described as nimble or cunning, rather than dense. As a mystery box, Marjorie Prime may have been presented by another director as a puzzle to be solved rather than a film to be enjoyed. The film’s plot could have been laced with clues to draw our attention and encourage us to solve the box’s mysteries before its inventor tips their hand. Neither Michawl Almereyda nor his viewers care about him or his viewers outsmarting each other. If you’re a fan of his work or not, you can’t ignore how nicely he’s aged as a filmmaker. So it’s only fitting that this film is about aging and the accompanying melancholy and boredom. Jordan Harrison’s Pulitzer Prize-nominated drama of the same name, Almereyda, tells the story of generational bereavement in which the elderly Marjorie (Lois Smith, reprising her part from the original play) is kept company by a hologram of her late husband, Walter (Jon Hamm). With a little help from modern technology, Tess (Geena Davis) and her husband Jon (Tim Robbins), Marjorie’s daughter and son-in-law, “Walter Prime,” looks and sounds just like their father. Tess thinks it’s all a little bizarre. Jon, on the other hand, seems less concerned about Walter, despite the fact that he was the one who bought him for Marjorie in the first place. When Almereyda begins his production, it is one that need multiple viewings over a period of time, so that the film can lose its meaning. “What’s the old saying about that?” It is possible that a falsehood repeated enough times becomes true? What makes Marjorie Prime what she is: the falsehoods we tell ourselves in order to get through our grief and life’s transitions In the words of Andy Crump

6. Short Term 12

Short Term 12 maintains a strict plot framework, but it never feels like a formula. In reality, the film offers as an excellent illustration of how invisibly screenplays may be included into films. Cretton effectively hides the film’s highly tuned story mechanics by enabling his characters’ illogical emotions to influence events and trigger important turning moments. A critical crisis appears to bring everything to a head, yet the novel finishes with a denouement that mirrors the beginning. In Cretton’s frank picture, we’re not convinced that Grace or anybody else has undergone a major transformation. As a result, it’s content to serve as a poignant reminder that cautious first steps may be just as engaging as enormous leaps of faith in storytelling. CURTIS WOLOSSCHUK—

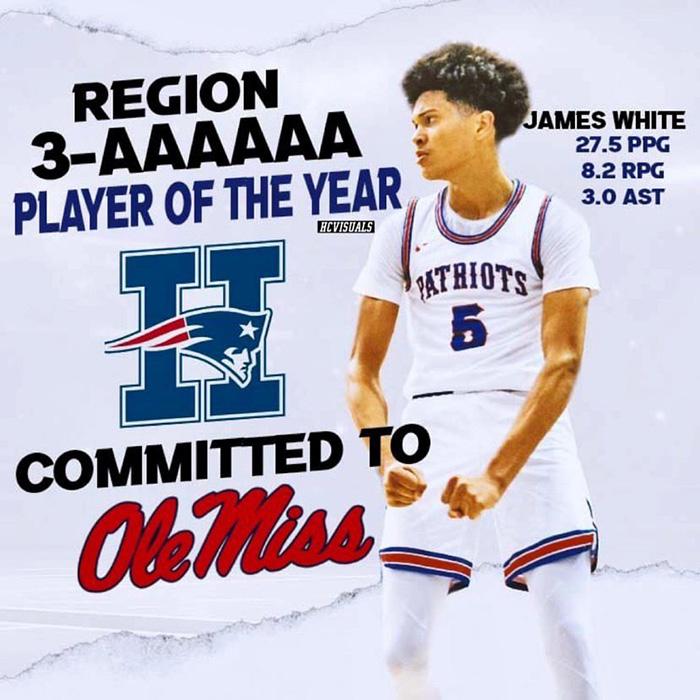

7. James White

While seeing James White, you’ll eventually come to the conclusion that you can’t catch a break with its protagonist. As soon as possible is best: Filmmaker Josh Mond’s feature-length debut is a modest wonder of even-handed sensitivity. While portraying James White in The Walking Dead, Christopher Abbott’s James White has a restless energy, self-destructive tendencies, an arrogant sense of entitlement, and fierce commitment to the people in his life. So, what does that mean for him? Is this a warning? To the point of indifference? It is possible that I am an unrecognized romantic. James White is unsure, but that doesn’t mean he doesn’t have strong feelings about its protagonist. Mond’s feelings for White are complex and intriguing, and he has nothing but admiration for her. In some ways, James White is loosely based on Mond’s own life. However, the jaggedness with which it is told gives the impression that the scenes in the film are only ripped-out patches on a much larger life quilt. Despite the film’s looseness, Mond’s tale is constructed with great care, keeping an eye on the emotional arc of White’s restless brain. At the beginning of the novel, White’s life is in turmoil, but it soon becomes clear that he has always been in a state of flux—only it’s that his long-distance father has passed away, and this has now become the focal point of his personal tornado. Gail White (Cynthia Nixon), White’s divorced mother who has stage 4 cancer, doesn’t need the added stress of White’s father’s death, which he barely knew. During the second part of James White, Abbott and Nixon burrow down as their characters continue down the road that only leads to one final destination, while Gail’s condition remains unchanged. Although Mond refuses to succumb to sentimentality or easy takeaways, he does so in spite of himself. In order to label James White’s story a “coming-of-age tale,” one must assume that the protagonist grows in a quantifiable, conventional manner. A change of heart might occur later on, but it will take more than an 85-minute video to do this. In the words of Tim Grierson: ”

8. Ida

When World War II has finished but is still present in people’s lives, Pawel Pawlikowski’s silent Polish film is a riveting investigation of how the past can impact us even when we don’t know anything about it. Agata Trzebuchowska, a non-professional performer, plays a nun-in-training who discovers that her family was Jewish and slain by the Nazis during the occupation of Poland. It is with her bitter, drunken aunt Wanda (Agata Kulesza) that she sets off on a quest to track down the final resting place of her long-lost relatives. The two protagonists’ connection becomes increasingly complicated as they descend deeper into the rabbit hole of their family’s history. To achieve a distinctive aesthetic, Ida is shot in black-and-white with an academy ratio of 1.37:1 by cinematographers Ryszard Lenczewski and?ukasz?al. Ida’s master could be lurking in that space, or it could be an empty blank; the effect can be both scary and interesting. Ida has to make her own decisions after a lifetime of certainty. As of this writing, Jeremy Mathews is no longer with the company.

9. Love & Mercy

Love & Mercy has a strange, at times sublime harmony to its dissonance. By following in the footsteps of his subject, filmmaker Bill Pohlad (known for 12 Years A Slave and In the Wild) refuses to succumb to sentimentality in telling the story of an uneasy pop star who longs for something more. (In one moment, Wilson debates with his bandmates about the Beach Boys’ real “surfing” cred.) Certainly, that’s the gist of it, but his technique reveals Wilson’s talent and suffering in all their complexity. As he comes to terms with the depth of his pain, classics like “In My Room” and “Wouldn’t It Be Nice” take on a new meaning. (Click here to read the complete review.) —Amanda Schurr’s

10. The Squid and the Whale

Squid and Whale borrows motifs from his previous films, including the children of divorced couples; individuals with bookish smarts who seem to be working against them; and an overall air of gloom and doom. His parents’ tumultuous marriage isn’t just a tidbit utilized to enhance the character of a specific person. A stunning, unvarnished depiction of a divorce’s chaotic collision from every viewpoint. As he told Paste in 2005, “It’s hard to even put myself in the mindset of those movies now.” The movie I identify with the most is Squid, since these are reimaginings of people who are close to me.” It is a logical extension of my intentions and feelings. When it came to this one, I had greater faith in myself. In the words of Keenan Mayo

Sources: https://www.lunchbox-productions.com

Categori: Entertaiment