Note from the Editor: “Is there a transcending aesthetic or manifestation of the sacred in cinema?” has been one of my recent concerns. Then how does it appear?” Aren’t there a lot of films that aren’t “Christian” but nevertheless have a spiritual significance, even holiness, to them? In an ongoing series of posts, I’ll examine films and their out-of-the-the-the-the-box connections with my faith. The first chapter is here.

- 6 Best Shows Like Kimi Ni Todoke That You Should Watching Update 04/2024

- 10 Best Movies Like Primal Fear That You Should Watching Update 04/2024

- 20 Best TV Shows Like Imposters That You Should Watching Update 04/2024

- 10 Best Anime Shows Like Tokyo Ghoul That You Should Watching Update 04/2024

- 6 Similar Movies And TV Shows Like A Discovery Of Witches Update 04/2024

What is Regret?

When someone says, “I don’t believe in regrets,” I often wonder what they mean by that. Is it because they don’t believe in regret, or is it because we should ignore it when it creeps up on us? There are those voices in our heads that tell us we need more, we’re not happy, and so on. Is regret just one of those voices that tells us we’re missing out on something? Is it possible that our existence and our concept of grace, God, and eternity are dependent on our capacity for regret?

You Are Watching: 3 Best Movies About Regret That You Should Watching Update 04/2024

The latter is what I believe, which probably makes me seem like some sort of gloomy fatalist who listens to Elliott Smith a bit too much. Let me explain before you write me off as a glutton for existential agony: I don’t enjoy regret or guilt, which are regret’s near relatives. Because they point me to the other and to God, I respect them in a strange sort of way; I understand why they’re in me so strongly, eerily, and at times terribly.

“What if?” scenarios are continually being compared to our current situation in order to keep us from dwelling on the negative aspects of our current situation. We wonder what if I had done this or that differently at a specific moment in our lives? We may think, “What if I had their life?” or, “What if I had their success?” Our “self” is always depicted as a figure who is less than it may be because we are dissatisfied with our identity, and this dissatisfaction is at the heart of these notions. On a daily basis, I feel this sense of remorse. Having faith that I’m exactly where God wants me to be and that I’m part of a vast and flawless design provides some level of consolation. In spite of this, I can’t help but ponder what may have been, long for a time when all futures were equal.

In spite of our “think positive! Purpose-driven!” culture, I’m sure you’ve felt these aches as well. Although I’m no psychologist, theologian or self-help guru, I believe that acknowledging our regrets and working through them is a better way. Regret can strike me as both sad and beautiful in the same way that a sunset does, and I’d want to examine three films that have captured this dichotomy for me.

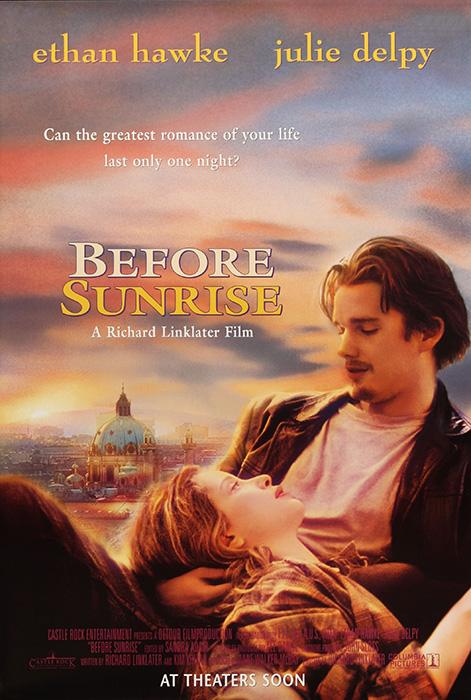

1. Before Sunset: The Jolt of Memory

Read More : 10 Will Ferrells Best Movies That You Should Watching Update 04/2024

If you haven’t seen Before Sunset (2004), please do so right away. But before you see Sunset, make sure you’ve seen 1995’s Before Sunrise. For one night in Vienna (Sunrise), an American guy (Ethan Hawke) and a French girl (Julie Delpy) meet by chance, and then 10 years later (Sunset), they meet again by chance (Sunset).

While the stories in these two films take place a decade apart, the aging of actors Hawke and Delpy and their more mature demeanors parallel the passage of time in real life. This is evident in both films. In Sunset, their characters are thrown together by coincidence and plunged back into the memories of that one night in Vienna all those years ago that they both remember so well. What happened since then? Whether it was the world or just their lives, Linklater follows them for the following 90 minutes as they stroll around Paris imagining what could have been.

Anyone who has ever been given a second chance to make amends can appreciate the film’s palpable feeling of urgency. Near the end of Sunset, Hawke and Delpy are in a car together, ostensibly at the end of their brief reunion, and they open out with agonizing honesty about their current discontents. Whenever I watch this scene, my heart bleeds afresh because there is so much truth about love, longing, and regret in it (miraculously performed by Hawke and Delpy). A decade later, each character reflects on what life would have been like if they had remained together after Vienna instead of splitting up. What about those old dreams? Is it too late to revisit them? Is there anything they can do now that they’ve moved on and formed “other” lives?

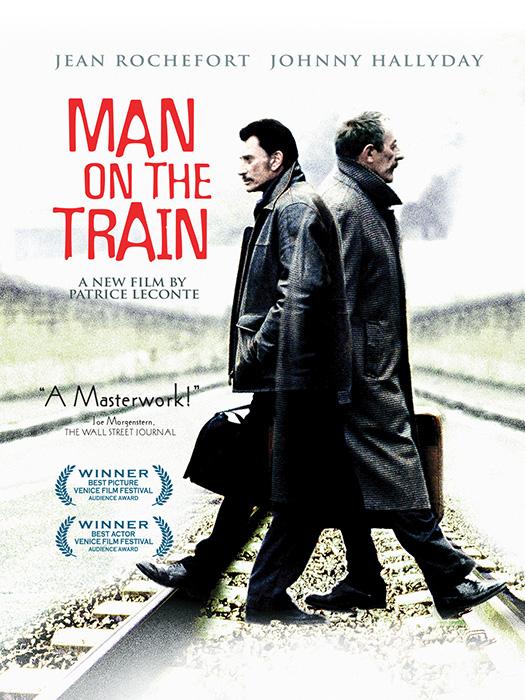

2. Man on the Train: The Pain of Identity

Director Patrice Leconte’s stunning French film, Man on the Train (L’Homme du train), explores the idea of what may have happened if some things had been different, not simply in terms of our daily lives but also our very identities. This film depicts two people whose paths unexpectedly converge in the same way that Sunrise/Sunset did.

Mr. Rogers-style loneliness and domesticity characterize Jean Rochefort’s role as an elderly teacher/poet. Leather-clad criminal Johnny Hallyday arrives in town on a train with no place to stay and no real enthusiasm for his upcoming crime. For a week, Rochefort’s character offers Hallyday a place to stay. A strange thing happens as the two men from different sides of the tracks (both metaphorically and literally) get to know one another better and better. Each of them begins to wonder if the other man’s life might have been a better fit for them. This unusual, rule-breaking life Rochefort never lived is represented by Hallyday to Rochefort. Moreover, Hallyday, who is worn out and jaded from his travels, finds Rochefort’s tranquil and stable life irresistible.

Read More : Top 14 Movies Like Molly’s Game That You Will Enjoy Watching Update 04/2024

It is only as the story progresses that we come to understand and empathize with these characters as they come face to face with the universal longing for another. It’s clear to us, and the two guys themselves know it, that they’re not meant to be together. It’s not that their desires aren’t genuine. Everyone has at some point wished they had a different identity, no matter how trivial or important. Even as we come to terms with the fact that we have some control over some aspects of who we are, we also come to terms with the fact that we have no control over other aspects of who we are. As Chesterton phrased it, “Ours is a life of holy unsettledness and divine discontent.” The fact that we can reflect on what is and wish for what is different suggests that the world is not what it should be.

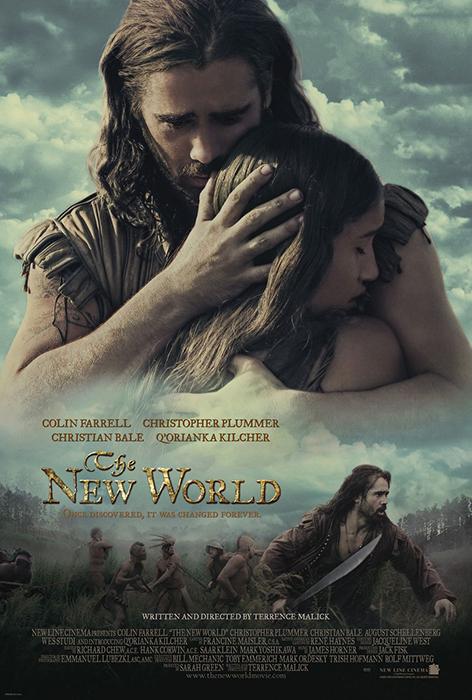

3. The New World: Regret and Renewal

Terrence Malick’s films always lift my spirits when I’m feeling down in the dumps (as anyone who knows me or has read my writings over the years will know). The New World, Terrence Malick’s most recent film, is a prime example of this. A cure for ordinary regret, in my opinion. “Pocahontas” is the narrative of a girl who is torn between two worlds, both of which utilize her for their own ends. She is left to make the most of a chaotic collision of forces and events that are beyond her control. Two-thirds of the film follows Pocahontas as she falls in love with John Smith, the wide-eyed, enthusiastic explorer (Colin Farrell). Smith, on the other hand, abandons her all of a sudden, giving in to the call of his own personal destiny. With her past life gone and a new existence at Jamestown before her, Pocahontas is a wreck, a prisoner foreigner among white settlers. At its simplest, regret is the knowledge that a once-in-a-lifetime experience has come to an end. In Pocahontas (now “Rebecca”), we witness this crystallization in her haunted eyes.

However, Pocahontas is not paralyzed by this recollection—this regret—which instead strengthens her and gradually fades. When Christian Bale’s John Rolfe (Christian Bale) shows up, Rebecca decides to leave. During a visit from John Smith in England, Rolfe reveals that he is the only one who still harbors feelings of sorrow. “All this pain will give you strength and point you in a higher direction,” Mary, Rebecca’s handmaiden, advised. Trees grow around their roots in the same way. It doesn’t matter if a branch falls off: “It continues to reach… towards the light.”

The tree, a recurring motif in several of Malick’s films, including World, serves as a useful metaphor for contemplating both regret and rejuvenation. Each of our lives might be likened to a tree, and our regrets are the branches that have broken off and fallen to the ground. Seeing these once-vibrant shoots of our life, these dreams that had so much potential, rotting and dying is a painful thing to see. Despite the fact that we are losing branches, shedding leaves, and accumulating more detritus, we continue to grow. It is only a matter of time before the forest floor is littered with our branches and buds. We can’t escape the light’s call to move forward, upward, towards it. Still, like a tree with its branches, we are never far from our regrets. They may remain on the ground for many years, but eventually they decay and become the very nutrients that help us thrive.

Sources: https://www.lunchbox-productions.com

Categori: Entertaiment