Psycho is one of the greatest horror films ever made, but the 60s also brought us a slew of other classics, from psychological terrors to cheap exploitations to the first slasher pictures.

- 5 Best Movies About Strong Independent Woman Update 04/2024

- 10 Best Movies About Introverts That You Should Watching Update 04/2024

- 10 Movies About Black Singers That You Should Watching Update 04/2024

- 15 Best Anime Like Re Zero That You Should Watching Update 04/2024

- 16 Best Movies Like Walk The Line That You Will Enjoy Watching Update 04/2024

When it comes to horror films, the 1960s are a fascinating decade since the genre began so shockingly in 1960 that it was too much for most audiences. Shockingly, many of 1960’s classic shockers were so painful to watch that audiences and ratings boards couldn’t figure out how to respond to them other than banning and wishing they never had to see them again.

You Are Watching: 18 Best 60s Horror Movies That You Should Watching Update 04/2024

For the first time in cinematic history, audiences were able to witness things they had never seen before thanks to the deterioration of the American Production Code. Only the bloody shower scene was not enough to satisfy the viewer’s desire for more. Psycho was a huge hit in the United States, but studios feared audiences would revolt if any other filmmakers tried to push the boundaries of decadence as swiftly as Hitchcock (some revolted anyway). Editing scenes with apparent blood on hands, visible breast shadows, etc. was a challenge for Hitchcock when filming abroad. Eyes Without a Face, Peeping Tom, and Black Sunday were all prohibited in the same year because of their depictions of facial incisions. In addition, numerous countries refused to release Eyes Without a Face because of their controversial facial incisions.

Ritualistic killers were the subject of all of the flicks. Major studios reverted to ghost-based horrors in the 1960s, which were safer. Psychological horror films were also created by well-known directors.

Italians and low-budget exploitation American films were the ones to carry the bloodied swords given to them in 1960 by the films of that time period. Foreign filmmakers took it a step further, creating what we now refer to as slashers (in Italy, they were giallos). The American Production Code was abolished in 1968. And so the bloody gates were swung wide open.

This collection of the top horror films from the ’60s illustrates the genre’s erratic rise and fall in popularity. As many ratings boards around the world would do by this decade to signify the appropriate age (17 in some territories, 18 in others) to watch the horrors of the 1970s, I rounded up to 18 when discussing the shocking year of 1960, ghost stories, giallo, psychological terror, and parables of distrust.

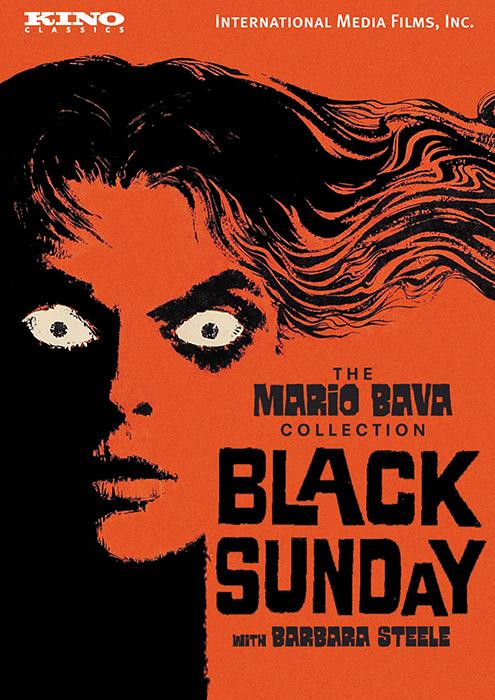

1. Black Sunday (1960)

This gothic throwback from Mario Bava, before he developed the first recognizable Italian slasher films known as giallos, could easily stand up to the greatest of Hammer Films’ production of the previous decade. A breathtaking and horrifying opening sequence would get the picture banned in the UK for years, despite the fact that it is nowhere near as violent as Bava’s works would become less than a half-century later.

Princess Asa (Barbara Steele) is condemned of being a witch and gets a large and spiky demonic mask nailed to her face with a giant mallet in the opening scene of the film. In a crypt, she is buried with her lover. A bat attacks two doctors 200 years later, and blood spills on her coffin. Satanic Princess’ disguise is peeled off and she takes possession of another virginal woman in town (Steele again) and sets out to exact her retribution on the townspeople.

While some may argue that Bava’s first great horror film, Black Sunday, was too extreme, it’s appropriate to see him perfect his skill in the boundaries of classic horror before inventing his own unique cinematic language.

2. Eyes Without a Face (1960)

French Cinematheque founder Georges Franju was a key figure in the emergence of the New Wave of French cinema. To prevent film cans from being destroyed, he’d labored nonstop throughout World War II. Clearly, Franju was a fan of the moving picture. Eyes Without a Face, the film he directed and which remains his most cherished work, relies on a single image to set the tone for the entire film.

Filmmaker Franju follows a plastic surgeon who specialized in transplanting living skin tissue. For the sake of his daughter, he kidnaps women and flays their skin, in the hope that it will give her a new face; when it fails he has an assistant dispose of the bodies in the river, which he then disposes of. In the meantime, his daughter watches in suspense as a new face appears behind a white mask, almost ghostly in appearance. With only eye movement beneath an indifferent facade, Scob and Franju display sadness not only for themselves, but also for the victims her father is trying to graft her onto.

3. Peeping Tom'(1960)

Peeping Tom caused such hysteria among moviegoers that it was removed from theaters. Many British film fans were hurt and betrayed by Michael Powell (The Red Shoes), one of the most highly regarded and optimistic directors in the country. A sleazy photographer/amateur filmmaker (Karl Boehm) who takes nudist photos for extra cash but gets his real joys from filming ladies while he stabs them to death with a blade on his tripod forced viewers to confront the level of thrill seeking they aspire to acquire from a moving image.

He attempts to reform when he develops a friendship with his neighbor down the hall, but his insanity goes well beyond thrills and discloses an evil experiment in dread, with his father as the controller and he as the subject, in which the photographer is both controller and subject. To convey to the audience that filmmaking is delivering something to voyeurs, Powell employs the grainy mouth-open screams of women in his films. In other words, the man who Boehm sees shopping for nude images in a shop but declines to buy one denies that there are tiers. When you have a picture, you may keep your fantasy in your own hands. In a film, someone else is in charge of your imagination, and all you have to do is watch.

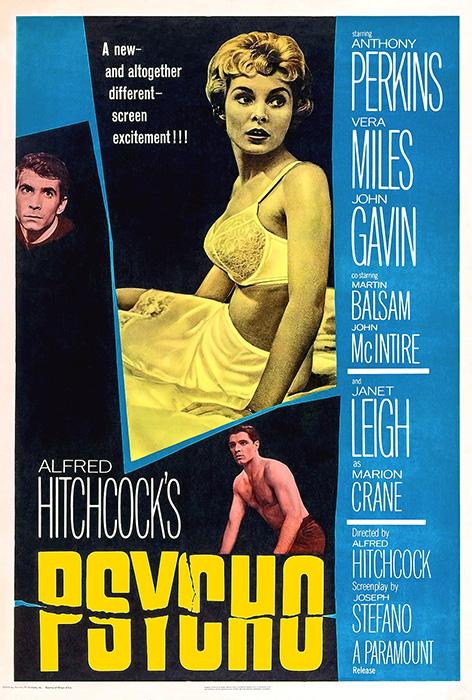

4. Psycho (1960)

Psycho by Alfred Hitchcock tops this list. Our heroine (Janet Leigh) is murdered in the shower by 77 camera angles and nearly as many cuts (and string shrieks from composer Bernard Herrmann). It’s one of the greatest cinematic scenes ever. Three minutes in, and there’s so much to grasp; everything in this scenario is so close and disturbing that creates the impression of visual processing itself, as the eye feeds violence down into our own minds.

However, the rest of the film is just as good as the opening sequence. Creating completely formed characters that he knew he would kill off or introduce midway through Psycho is one of Hitchock’s most impressive achievements. It’s a risk few horror films are willing to take: showing the bond between the killer and the victim who won’t make it out alive. If we don’t need them with us every step of the way, we don’t need them.

Psycho is a film-muscle flex. He understands that the very act of filmmaking is presenting something to voyeurs, and like Powell, Hitchcock knows that the audience will recoil, even though he’s repeating the same anti-Production Code act that the very audience did at the start of the movie, which many in the audience likely enjoyed.

5. The Innocents(1961)

The Innocents features some of the most haunting cinematography ever seen in a horror film. What we do in the shadows is the focus of this ghost story, both narratively and in its visuals. Although candle flickers and the area under a doorway are made more unsettling by the black-and-white cinematography, director Jack Clayton also uses it to illustrate how religious dogmatism based on right and wrong can drive people insane. In The Innocents, we’re never quite sure if the ghosts are real or a representation of a mind that’s shamed itself for losing their innocence..

Read More : 10 Best Heist Movies Netflix That You Should Watching Update 04/2024

For her part, Deborah Kerr plays an orphan caretaker who is convinced that her home and the two orphaned children she looks after have a supernatural presence that is bent on gaining control of the children. After hearing the children’s uncle (a sleazy Michael Redgrave) speak about a sexual encounter, she gets her first feeling of a haunting. It appears that the children were exposed to sexuality at an early age by the former governess and her brutish partner. Kerr’s governess may be so sexually repressed that her desire to care for children may be a substitute for feelings of attraction to their uncle, who has been around for a long time. Clayton and cinematographer Freddie Francis discover a sense of foreboding in every corner thanks to her ability to discern haunting spirits, whether or not they’re actually present. Truman Capote, the scriptwriter, pulls a fast one on Henry James’ novella The Turning of the Screw by introducing a locket and photograph considerably earlier in the film than James did in the novella, an achievement that should be recognized.

6. The Birds(1963)

To make The Birds, Alfred Hitchcock had to deal with a large number of birds and archaic equipment. Due to developments in technology, we can see that the birds diving over the actors’ reactions in most assault sequences are superimposed on top of a different frame, which means it doesn’t hold up as well as some of his other classics. It also lacks a compelling conclusion or an emotional backbone to keep us engaged throughout the barrage of assaults. Even if The Birds hasn’t held up as well as some of the Master’s other works, there are still many brilliant moments to be found in this picture.

In spite of this, The Birds had an excellent home invasion sequence that tremendously influenced subsequent zombie and home invasion films. Tippi Hedren’s residence is swarmed by birds that have started attacking humans for no apparent reason and appear to have a special bone to pick with the socialite, who was recently in court for her raunchy conduct. It’s like playing Whack-a-Mole with their beaks poking through the walls. Love interest Robert Taylor must board up the doors and nail furniture in front of vulnerable locations to protect her from harm.

The Birds demonstrates all of the survival techniques we’ve learned from zombie flicks, as well as the fatalist moment when the protagonist heads upstairs. Always keep your feet on the ground.

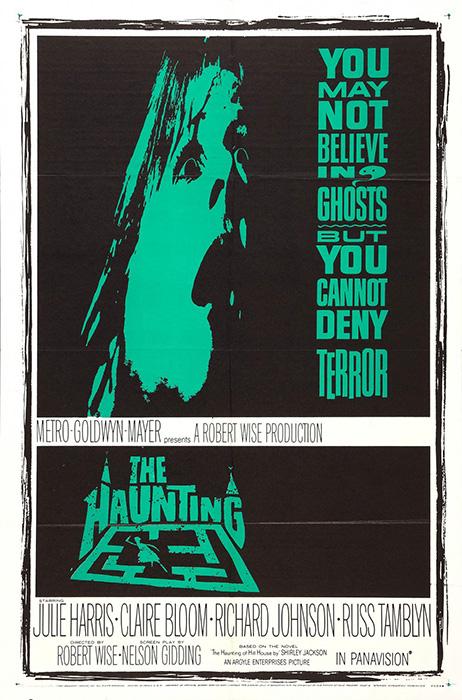

7. The Haunting (1963)

A lot of the best ghost stories play with our skepticism about whether or not our characters are really being plagued by ghosts, or if their minds are simply filling in the blanks due to strange sounds and forgotten locations of objects. “The Haunting” presents this as a challenge in Robert Wise’s film.” Haunting, death, and insane stories have been passed down from generation to generation in this eerie mansion. For this reason, researchers in the paranormal are paid to remain in the house for a few days and offer him answers for the house’s haunting.

Is the house on the hill really haunted, or is it just an urban legend? Or does the fact that it’s supposedly haunted play a role in people’s minds? Some people still have doubts. I’m not one of those people. Because both doubt and belief will continue to send individuals to the house for explanations, it appears that the house desires both reactions.

8. Blood and Black Lace (1964)

With Blood and Black Lace, Mario Bava revolutionized the horror genre. It’s hard to overstate how influential Bava was in the giallo (Italian bloodletter) genre, which was born out of Bava’s highly stylized and gruesome killing techniques, interesting point-of-view shots that withheld the killer’s identity while also allowing for close vantage points for cutting and strangling, and vibrant colors.

Black and Red Models are being murdered in Lace’s location, a fashion house Killer in black gloves, cap and trench coat, with switchblade and wires in their pockets. This will become the standard for giallo villains in the future. Using a wicked face, Bava arranges one hunt in a room full of mannequins, where the model is dispatched as soon as the industry gets rid of those dead; witnesses are as mute and faceless to industrial methods as the mannequins are to the murders. “

9. Hush… Hush, Sweet Charlotte (1964)

Prior to the term “diva camp” being coined, Robert Aldrich had already pioneered the genre. For the first time, a faded Hollywood star was used in a film, but it was presented as a pathological desire for continuing adulation. “Whatever happened to Baby Jane?” was a 1962 film that featured two sisters who used to be stars torturing each other in an inconspicuous apartment complex. Bette Davis and Joan Crawford were able to go full on insane.

Aldrich’s Hush… Hush, Sweet Charlotte is the winner here, even if Baby Jane has some horror overtones (Crawford is bound to a bed and hungry when she isn’t being fed rats). There are a lot of similarities between the stories in terms of structure. Both of them begin with some form of violence. A dysfunctional Bette Davis and an unrevealed family secret are at the heart of both of these stories (here, Olivia de Havilland subs for Crawford, who was originally cast, but dropped out, probably aware that Davis once again had the juicier role; although de Havilland perhaps knows better how to step back from Davis and not try and match her, but be more secretive in her performance). Charlotte, on the other hand, is more elegant and gothic than Baby Jane ever was. Certainly one of the most horrific scenes in that period’s cinema, Bruce Dern’s murder with a butcher cleaver stands out. Before the next strike, he loses a limb. However, even though there is blood on Charlotte’s clothing due to her family’s reputation, she is essentially merely ordered to stay in her southern house and not trouble anyone. A shotgun is pointed at the developers seeking to build a freeway through her land when we first meet Charlotte as an adult (Davis). She also experiences night visitation from the ghosts of men who were murdered in the house, and new blood appears on her clothing once more.

What a hoot Baby Jane was! There are magnolia tree ghosts and shattered limbs in Sweet Charlotte. Camp and high camp are two different things. Camp, as the name suggests, was initially coined by Susan Sontag back in 1964, in an essay.

10. Repulsion (1965)

To see a shattered lady who is afraid of being penetrated by every male she comes into contact with in Roman Polanski’s first English-language picture Polanski’s personal life afterwards took bizarre and crooked turns that caused the film to splinter into new cracks (the brainwashed cult murder of his wife and child, and his drugged rape of a teenager). Repulsion conveys the message that no one is in complete command of their thoughts. The fear of sex is definitely out of control for Carole (Catherine Deneuve) (with small hints of previous abuse). Hands smash through the wall, and she imagines them raping her in the corner of a room. These visions have left her immobilized and almost silent, paralyzing her ability to speak.

While not every man is capable of rape, there is a sense that the men can’t help but succumb to the temptation of a woman like Deneuve’s beauty. Polanski uses a very transparent nightgown to film most of her breakdowns. Perhaps Polanski feels that he should present evidence that she should truly be terrified. I don’t think it’s gratuitous. She’s cradled by the man who assists her even when she’s had a complete meltdown and needs to be lifted off the floor. The scene is filmed like the successful conquest of carrying a virgin into the bedroom for the first time. After learning about Polanski’s damaged life, Repulsion becomes even more psychological and, at times, unpleasant.

11. Kill Baby, Kill! (1966)

Kill Baby, Kill! by Mario Bava is the Citizen Kane of giallos. Everywhere you look, you can hear the impact of Dario Argento and other blood-splatterers such as Reservoir Dogs. In Bava’s color palette, every eerie location for a possible murder seems like a stained glass window that’s about to be stained red. Goblin’s electro-scores have a soundtrack full of eerie sighs and gasps. In addition, Bava uses imaginative camera zooms on spiral stairs and a camera point of view from a swing set to create some of his most memorable shots. For the next 30 years, these themes would be found in the best Italian shockers. A better name might have made Kill Baby, Kill! one of the greatest horror flicks of all time.

Horses stomp a girl to death in the Transylvanian town of Kill Baby, Kill! The ghost of the girl haunts the village. As soon as she makes eye contact with you, you will be subjected to mind control and die in a dreadful way. In 1966, it would have been shocking to see a cemetery covered in mist, thick cobwebs, neck cuts, punctured temples, and impalements. For more than half a century, the singularity of Bava’s camera choices have resonated, inspiring the quiet gasping and shuddering that would one day fill the soundscape of shock film.

12. Seconds(1966)

There are some strong horror themes, although the film is more of a thriller than horror. John Frankenheimer made Seconds, an anti-mainstream/anti-counterculture story about aging. When a dead man’s phone rings, a secret society is hidden beneath a slaughterhouse, and a bandage conceals a secret identity. The famous cinematographer James Wong Howe also uses several hazy, fish-eye lens camera setups to convey a huge feeling of fear, make you question whether what you’re witnessing is genuine, and it might be said that the demon rape ceremony in Rosemary’s Baby two years later heavily affected it.

This phone contact comes from a man John Randolph believes to be dead, but who claims to know things that only the man Randolph thinks is dead would be aware of. There is a company that can spoof your death and provide you with a new body and identity in order to integrate you into a group of people who are living their second chance at life. He does not say that he is stuck in an eternal waiting room trying to return to the life he left behind but must recruit a new body in order to leave this place. Because the company also drugs and films their subjects engaging in heinous acts for blackmail reasons, there is no way out of this situation Randolph becomes a younger Rock Hudson, but he has no free will and no means of escaping.

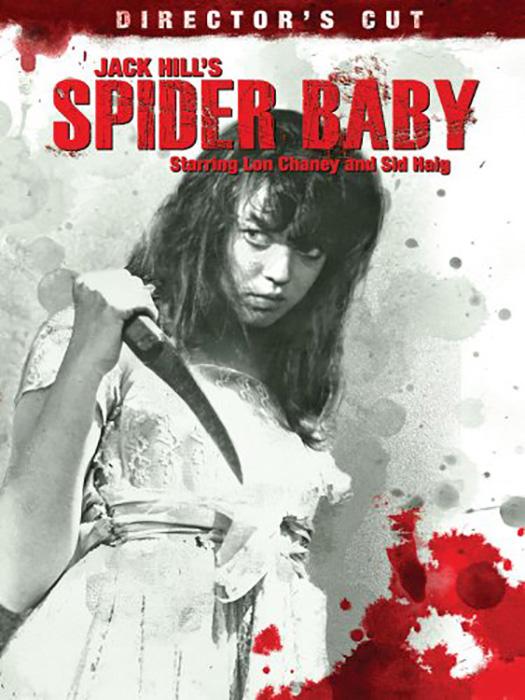

13. Spider Baby (1967)

Spider Baby is the best authentic American exploitation horror picture of the decade, even if it has a few touches of comedy and exploitation (with an all knowing hat tip to Hershel Gordon Lewis, who pioneered gore effects during this decade, but his films never did much more than splatter blood and sputter dialogue). Everyone is “likely to end up in somebody’s tummy” after all, according to the song’s credit theme. Lon Chaney stars as a loving caretaker in Spider Baby, a film about his experiences caring for a home filled with only his own kind. A degenerative brain illness causes them to have the cognitive abilities of five-year-olds, but with the drive to kill and devour everyone who isn’t a member of their family. In order to eradicate the gene from their bloodline, the extended family has left them to die out in a house, but of course, some people come seeking for an appraisal.

In Jack Hill’s film (Coffy), which is too strange for the mainstream, yet not violent enough for gore-heads, the audience is divided. If you combine Freaks, Two Thousand Maniacs, and lingerie chase scenes with the uncomfortably adult-bodied seduction skills of women who are frequently referred to as “children,” you have a lovely web of exploitation fun here.. One of the inbred “children” is Sig Haig from The Devil’s Rejects.

14.Kuroneko (1968)

There are several lists of the top 1960s horror films that include Masaki Kobayashi’s hypnotic tetraptych of ghostly folktales, Kwaidan (The Four Ghost Tales). It has a poetic quality about it. It’s a bold move. Haunting is the best way to describe this piece of music. But it’s more contemplative and moralistic than harrowing. Kaneto Shindo’s Kuroneko (Black Cat) is instead chosen to exemplify Japan’s ascent to horror filmmaking in the 1960s. Both Kwaidan and this film are both poetic, haunting, and moralistic, but this film has more real-world horror than Kwaidan. To keep their own spirits from entering the hellish gates of hell, seductive ghouls kill Samurai and draw blood from the necks of unsuspecting men, while a house that was burned to the ground reappears spectrally. No doubt about it, this is a horror picture.

In addition to being the ex-wives and mothers of soldiers, Kiwako Taichi and Nobuko Otowa, the vengeful spirits with a samurai’s bloodlust roam the land (Kichiemon Nakamura). For the past few years, the soldier has been engaged in combat far from home. In the meantime, his wife and mother are kidnapped by a group of samurai and raped before being set on fire in their home. After a black cat eats their bodies, their souls make a contract with the devil to continue killing all samurai; they get near to them through seduction and then consume their blood. However, due to his courage in combat, the husband is promoted to the rank of samurai, and his wife and mother are left with the difficult decision of whether or not to keep him.

In Shindo’s film, the samurai literature and cinema are rebutted by a stunningly beautiful response. There is only one warrior who shows concern for anyone beyond himself and his own desire in the story, and that is his brave wife’s husband. Abuse of power has nothing to do with samurai.

15. Night of the Living Dead (1968)

But even if they’re named “ghouls” in George A. Romero’s Night of the Living Dead, these zombies are nonetheless what we know them to be: blank, unthinking monsters who stagger around with empty glances and barely retain any sense of their humanity. As a result, our heroes with brains have tended to find enormous pleasure in seeing them annihilate the undead. After all, they’re no longer human.

Watch Romero’s film a second time and resist the urge to empathize with the “ghouls” more than you do with the vast majority of the human characters. Prejudice, xenophobia, and self-centeredness are among the most commonly held human traits still in use today. In spite of his courageous fight against the ghouls, the most selfless non-ghoul we follow (Duane Jones) is famously shot because the man on the other end of the gun perceives his skin color as a cause for suspicion. But Night of the Living Dead is littered with Romero’s skepticism of authority tropes. Because of public dissatisfaction with law enforcement, generals, and soldiers’ motives during the Vietnam War and Civil Rights Movement, public opinion had evolved away from blind faith in their good intentions by 1968. After all, they are only human, and many of us carry malice toward others. The only way to avoid thinking about the horrifying xenophobia that led to this massacre is to witness a mound of ghouls who were once humans being pulled out of the ground and set on fire.

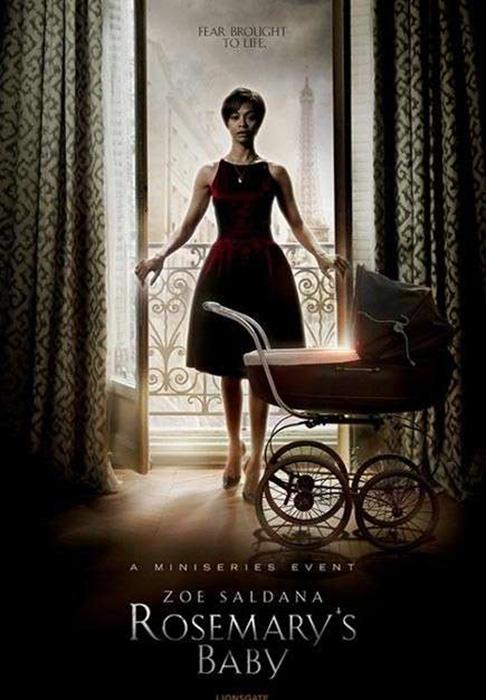

16. Rosemary’s Baby'(1968)

Rosemary’s Baby is my favorite horror film ever. It’s so effective at every level. When we first meet Rosemary (Mia Farrow) and Guy (John Cassavetes), they’re looking for a new apartment in Manhattan and everything seems perfect. However, when one person is lacking, the relationship suffers as a result. When Rosemary tells people about Guy’s two plays and commercials, he’s a failing actor. Guy sees this as a reminder of his perceived failure, rather than a source of encouragement. Ruth Gordon and Sidney Blackmer, two elderly kooks who live down the hall in their new apartment complex, become fast friends with the couple.

Rosemary slips off to sleep on a bed of water while Guy, the neighbors, and other creeps watch the monster scratch and stab and do nothing to save her as she cries. She wakes up naked and covered with claw marks in the morning. His wife’s spouse claims that he decided to conceive her even though she was asleep because he was in the mood and they’d spoken about it beforehand. If she was “drunk,” so what? The Devil raped Rosemary and Guy promised the Devil’s child to their Satanist neighbors to improve his career, Rosemary believes.

In addition to being one of cinema’s most horrific and compelling sequences, the ceremony is one of cinema’s greatest transgressions. There is a violation of trust and body in the ceremony, but Guy’s lax cover-up of “I wanted you right then” further insults Guy’s lack of honesty. When it comes to making decisions about her body, Rosemary is utterly powerless in the rest of the film. Aside from Dr. Hill (Charles Grodin), the doctor she trusts, he gives her over to a different doctor because he thinks she’s unstable, even though she chose him herself. Every male thinks she has no concept what is going on in her body, and she is completely ignored by them. Despite the fact that many men are still fuzzy and woozy (like Rosemary on her drugged bed), Rosemary’s Baby is still one of the most terrifying and necessary films ever made.

17. Blind Beast'(1969)

The film Blind Beast, directed by Yasuzo Masumura, accomplishes the challenging task of depicting the physical feelings of blindness on film. Dismemberment is also a major theme in this film. Although it’s a rather intense and skillfully done exploitation film, it serves as a distinct precursor to the kind of compulsive bodily alteration employed for both pleasure and suffering in the utterly unique Tetsuo: Iron Man series that followed.

When a devoted mother kidnaps a model (Mako Midori) and throws her into a huge sculpture studio with no windows, the story of Blind Beast begins. It’s filled with sculptures made by her son, Eiji Funakoshi, who is blind. One resting place is between the breasts, while another one is sloped down a clay stomach to another. He craves a new specimen to learn about each part of her body through touch and transform into his best work. She resists (and the shifting of rape into submissiveness, then into seduction, then into enjoyment are murky here, but never played up for titillation) but eventually becomes so in-tuned to his senses that she desires to go blind as well. Morbid fantasies give way to self-destruction as they work together to learn more about the human body in a new and frightening way.

This is a difficult film, not because of its violence, but because of its ideas. When you play Blind Beast, the most terrifying part isn’t so much what you see as how your brain interprets what you see. Intimacy and torturousness both have their moments, and they are both met with a mindful urgency.

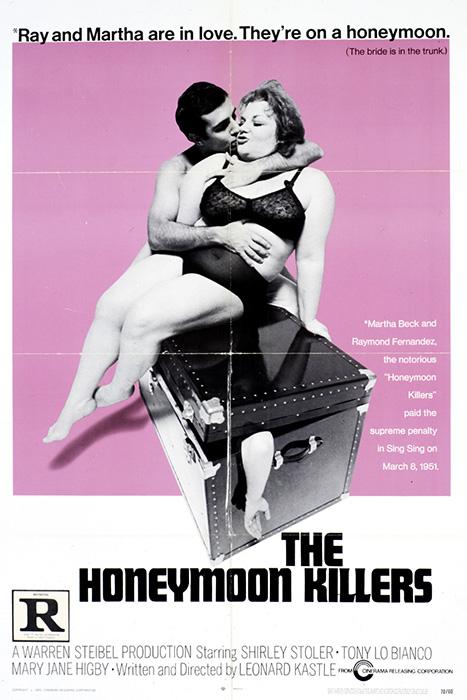

18. The Honeymoon Killers (1969)

The final film on my list isn’t strictly a horror film, but it does enter the conversation about the genre in the same way that Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer does. The Honeymoon Killers, directed by Leonard Kastle, was one of the most naturally shot films about serial killers at the time. With its full-body framing, it emphasizes how much suffering the lady on the receiving end feels and the “why don’t you just die already” response she receives, as well as how much she screams, “You’re going to die.” The “Lonely-hearts Killers” committed murder after murder just two years after Kastle made a film that didn’t romanticize violence as a lyrical massacre but presented it in such a factual manner that you feel like you’re in the living room watching them commit murder after murder in slow motion. At a 1969 screening, Variety gave it an enthusiastic review; nevertheless, it was not picked up by a distributor until the following year. Francois Truffaut, one of the most important figures in the French New Wave, regarded it as his favorite American film, and it was banned in many countries until the 1980s.

When Shirley Stoler and Tony Lo Bianco met through a newspaper pen buddy service, they were looking for a new love interest. In the film, Ray (Lo Bianco) is a conman who gains the trust of the lady and receives free housing, offers marriage, and then kills them. The only thing he doesn’t do is kill Martha (Stoler). She gets jealous when she sees the other woman beaming in his presence as he picks up new victims. Martha begins to kill more ferociously and passionately, in an effort to free herself from her captivity and continue her relationship with the man she has come to love.

The Honeymoon Killers, in contrast to the giallo films that came before it and the slasher films of the 1970s, avoids showiness. Indeed, the original director, Martin Scorsese (!), was fired because he spent too much time shooting dark insert shots that slowed down the production (like shots of garbage left at the beach). Kastle, the screenwriter, stepped in to finish and direct his sole picture because the budget didn’t allow for any additional days. Filmed like a documentary, the sound is uneven, and the mis-en-scene is typical of a novice. When you hear Gustav Mahler’s symphonies in the background, you know this isn’t some unauthorized home movie. Unlike most beginner films, The Honeymoon Killers feels innovative.

Sources: https://www.lunchbox-productions.com

Categori: Entertaiment