Please play the symphony of sounds… It’s your one-stop shop for the best French films of all time! Alternatively, you may already know your Malle from your Melville and have a working knowledge of the Nouvelle Vague dialects. Alternatively, your understanding of French cinema may be restricted to ‘Amélie’ – or at the very least, ‘Untouchable’. In either case, this list of the top French films released between 1902 and 2019 is sure to pique your interest.

- 10 Best Romance Anime On Netflix That You Should Watching Update 04/2024

- 13 Best Biography Movies That You Should Watching Update 04/2024

- 10 Best Movies Like Sleeping With Other People Update 04/2024

- 15 Best Movies About Social Media That You Should Watching Update 04/2024

- 19 Best Shows Like Ravenswood That You Should Watching Update 04/2024

If you’re in Paris for more than a few days, don’t miss out on the city’s cinema bars, where you can relax with a drink before heading to an indie cinema. Visit the locations used in the 50 best films shot in Paris while you’re there for some real-life location scouting.

You Are Watching: 15 Best French Movies Of All Time That You Should Watching Update 04/2024

We’ll send you emails about the latest news, events, offers, or promotions we’ve partnered with, and you’ll agree to receive them by providing your email address.

Best French movies

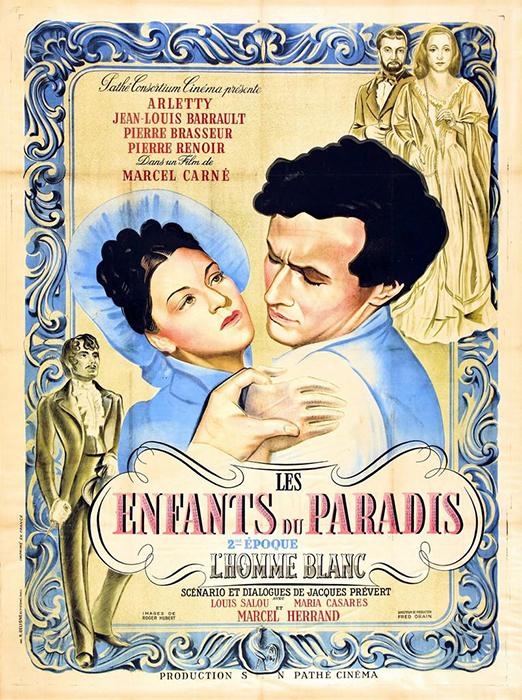

1. Les Enfants du Paradis (1943)

‘France’s answer to Gone with the Wind!’ is Marcel Carné’s 1945 literary romance starring Arletty, a sphinx-like ice maiden in the league of Marlene Dietrich who, in nearly every shot, has her eyes masked by a beam of light. Garence is a conflicted, sphinx-like ice maiden in the league of Marlene Dietrich. It is a picture that relies on a brilliant, funny narrative (written by Jacques Prévert), lavish set design, and superb actors to give the story its life.

2. La Règle du Jeu (1939)

The statement ‘everyone has their reasons’ epitomizes Renoir’s wonderful social comedy, which was banned on its original release as ‘too demoralizing’ and only re-released in its original form in 1956. From farce to farce, from reality to imagination, and from comedy to tragedy, the film focuses on the Marquis de la Chesnaye (Gregor Dalio) and his wife (Dalio, Gregor) as they host a sumptuous country house party. With an unblinking eye that refuses to judge, romantic intrigues, societal rivalries, and human foible can all be viewed with an open mind. In addition to Renoir’s personal performance and the rabbit shoot, there are also hints of mortality in the after-dinner entertainment. French social stratification is depicted in the film, from the aristocratic hosts to a petty class-discrimination poacher who ends up working for them.

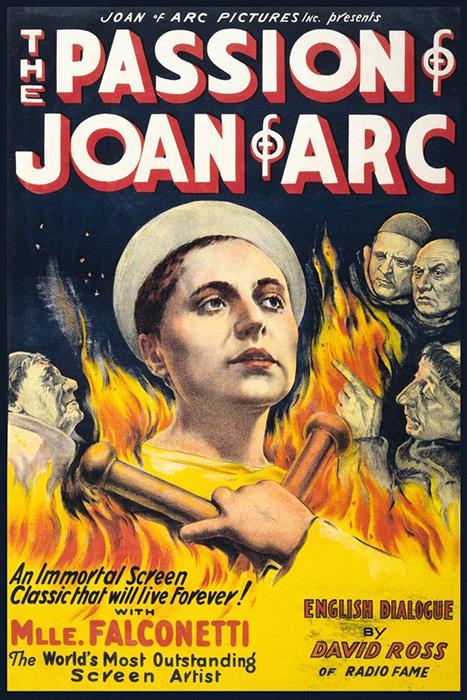

3. The Passion of Joan of Arc (1927)

Even today, Dreyer’s most generally recognized masterwork remains one of the most staggeringly intense films ever made. Closeups of hands, robes, crosses, metal bars (and (most of all) faces dominate the film’s focus on the closing moments of Joan’s trial and her execution. Naturally, Falconetti’s Joan is the face that we see the most, and it’s hard to think of a performer who embodies both physical pain and spiritual ecstasy more vividly. It is surrounded by other individuals and sets that are similarly stripped of adornment and transmit both tangible and metaphysical essences in a similar way. Magnificent cinema, and almost painfully affecting, is what you get from this picture. It’s less molded in light than carved in stone. TR

4. Playtime (1967)

Read More : 14 Best Movies About D Day That You Should Watching Update 04/2024

While on a 24-hour tour, Tati’s Hulot and a group of pleasant American matrons encounter each other on the streets of Paris. It’s not so much a story of the individual against a progressively dehumanized environment, but rather a semi-celebration of Tati’s magnificent city set, which is all reflections and rectangles, steel, chrome, dazzling sheet metal, and trompe-l’oeil plate glass. This masterpiece of Tati’s career is a surreal comedic vision on the point of abstraction, shot in color that looks almost like monochrome, recorded in five-track stereo sound with barely a word of spoken (the enigmatic language of things echoes louder than words). SJO

5. Le Mépris (1967)

The snub. “Contempt” is the French word for this feeling, and it’s what Camille, Paul’s girlfriend, feels for him when he’s summonsed to Rome’s Cinecittà film studios and the beautiful island of Capri to assist Fritz Lang (playing himself) in improving their film version of Homer’s ‘The Odyssey’. As Paul is both attracted and repulsed by the world of filmmaking throughout the film, we see Camille and Paul’s relationship crumble. You’ll see the best of Jean-Luc Godard and his team at their very best in the cinematography of Raoul Coutard; the musical compositions of Georges Delerue; and the editing of Agnès Guillemot. It’s the ultimate expression of Godard’s difficult connection with his art, like Camille and Paul’s love-hate relationship. DC

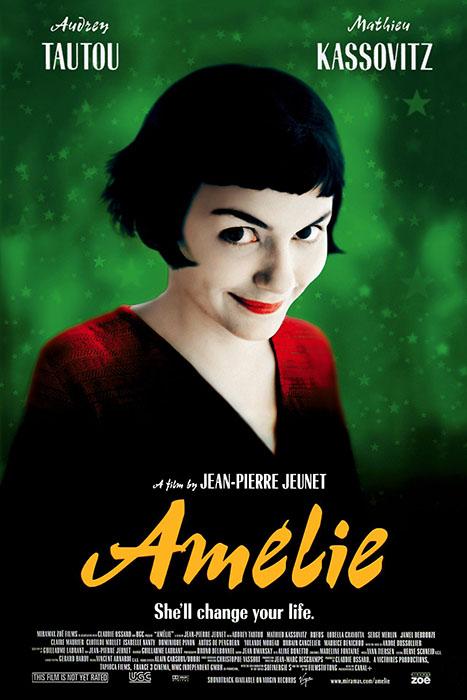

6. Amélie (2001)

Jean-Pierre Jeunet’s rose-tinted Parisian romance is likely to be the part Audrey Tautou will be remembered for the rest of her life. As a quirky one-off, the picture retains an allure all its own because of the way it feels like it’s the product of the writer-distinct director’s sensibility and perspective. This film still has a lot going for it: watching it is like being carried along by an ocean current full of clever quips and wacky insights. DJ

7. L’Atalante (1934)

‘L’Atalante’, Jean Vigo’s only film, was made in 1934 after the director’s death from tuberculosis. Instead of a movie, what we have here is 89 of the busiest and most beautiful minutes ever shot on celluloid, condensed into a single aesthetic vision. Jean (Jean Dasté) is the captain of L’Atalante, a filthy barge that plys the canals of rural France. Juliette, played by Dita Parlo, is the small-town girl he married off to him. Juliette is torn between her love for Jean and her yearning to experience the world outside the limitations of the boat as she sets foot on board the vessel. The issue is made more worse by Jean’s obnoxious first mate Pére Jules, who refuses to leave Jean alone (Michel Simon). There’s no way to describe it, but it’s somewhere between humor and tragedy as well as romantic and real-life scenes.

8. Cléo from 5 to 7 (1962)

French new waver Agnès Varda’s second film, ‘Cléo from 5 to 7,’ was released in 1962 and showcases the city of Paris in all its glory. As a worried and fame-obsessed singer, Cléo (Corinne Marchand) tells herself, ‘Hold on, gorgeous butterfly!’ as she prepares to wander the city for two hours in anticipation of a potentially historic medical verdict. Filmmaking style is experimental and free-wheeling: Varda provides us overlapping speech, parody inserts, a documentarist’s eye coupled with a painter’s, found sound and Michel Legrand’s music, and juxtaposes frippery with political truth. Varda’s delicate and unforced approach of depicting the ebb and flow of life, love, and desire is exemplified in this quietly moving and meaningful piece. WH

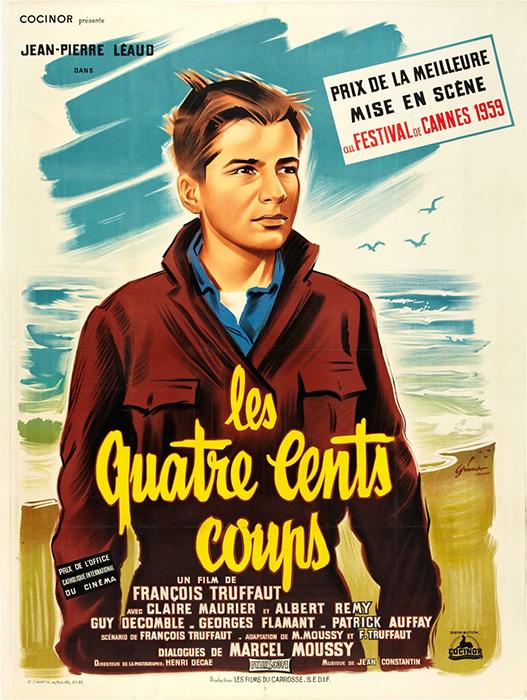

9. The 400 Blows (1959)

French New Wave film The 400 Blows was written and directed by Francois Truffaut, a neglected son, passionate reader, delinquent student and cinephile, in 1959. In the film, which stars Jean-Pierre Léaud as Antoine Doinel, Truffaut shows that a good brain and bad parents do not necessarily make one a talented film director, but they will, one way or another, make him an unrepentant liar. It’s hard to believe that Antoine, an incompetent burglar who ends himself in prison, could be made into one of the most delightful cinematic experiences ever. Although the monochromatic ’50s Parisian cityscape lends itself well to the film, the enchantment lies in the former critic’s joy at getting his hands on a camera, which burbles through every shot.

10. La Belle et la Bête (1946)

Read More : 20 Best Movies About Incest That You Should Watching Update 04/2024

For Jean Cocteau’s joyous 1946 rendition of the Freudian legend about a vulnerable girl and an altruistic monster, we have a stunning, pin-sharp new restoration. This ‘Beauty and the Beast’ is pure fun, a self-conscious but never precious attempt to revisit childhood fancies and half-remembered visions, except from the rather pompous prelude. Terror, wonderment and grief are all feelings that one can experience at the castle of the cursed Beast, which is filled with grabbing hands. Even though the monster and the maiden have a strong connection, the film doesn’t bind the beast; rather, it lets him roam free. If you look at the film in its historical context, you’ll see that this kind of fantasy is still possible, and possibly more vital than ever, given that we’ve seen so much unthinkable tragedy in the last few years. TH

11. L’Armée des Ombres (1969)

Melville, the director best known for gangster classics like “The Samourai,” made this great late 1960s thriller as a quiet tribute to the heroes of the French Resistance during World War II. Melville’s film uses a formal essentialism to outline the codes and manners of impassive-looking ‘warriors,’ over whom the Damocles sword of discovery, torture, and death hovers, from October 1942 to February 1943, of a small group of field operatives, including Lino Ventura’s ex-engineer and Simone Signoret’s iron-nerved Mathilde. Pierre Lhomme, the cinematographer for the suspenseful, steely-grey color palette used for the twilight adventures of the film’s protagonists, has done an excellent job with the film’s visual quality, which makes the film’s emotional core even more powerful. Superb. WH

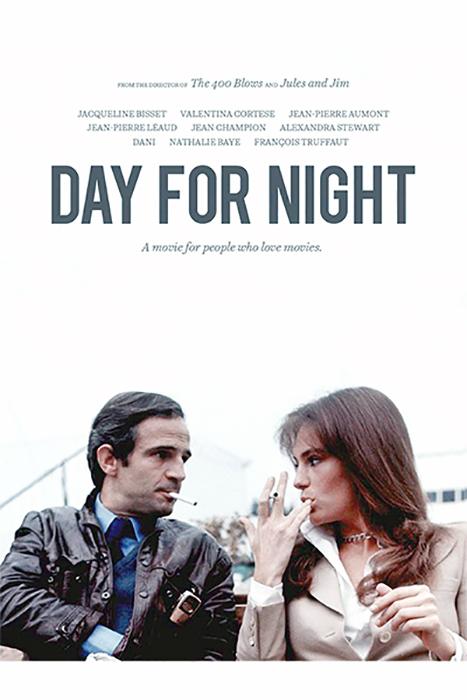

12. Day for Night (1973)

“Day for Night” hits the perfect balance between the operatic neuroses of “8 1/2” and the warm, pastel-hued nostalgia of “Singin’ in the Rain” in the pantheon of films about filmmaking. For his part, Truffaut dons the same sports jacket, shirt, and tie ensemble as in ‘Close Encounters of the Third Kind’ as indefatigable director Ferrand. He also gives the same coolly detached performance, but it works better in this situation than in others. For all of Jean-Pierre Léaud’s childishness and Jacqueline Bisset’s nervousness, it is recognized as part of the job. DJ

13. Les Demoiselles de Rochefort (1967)

One of Jacques Demy’s finest works, “Les Demoiselles de Rochefort,” is a dreamy, romantic, and ultimately fate-driven musical in which the classic Hollywood pattern of “putting on a show” is lovingly reinvented as a study on the emotional rollercoaster that is going to the movies. Cate and Francoise Dorléac star in this brilliant new print of the film about the “pair of twins, born under the sign of Gemini,” who leave Rochefort for the big city. A motorcycle exhibition arrives in town and the girls decide to put on one last act before packing up and moving on.. Gene Kelly, Danielle Darrieux, and Michel Piccoli all have memorable roles, but it’s Demy, with his contagious sense of humor and infectious good humor, who will most likely leave audiences in a state of awe. DJ

14. The Wages of Fear (1953)

Henri-Georges Clouzot, a French film director, has been compared to Alfred Hitchcock throughout his career, and he took it hard. Clouzot didn’t have to be concerned; on his best days, he was better. The ultimate psychosexual thriller, ‘Les Diaboliques’ (1955), is Hitchcock’s first attempt at the bomb-under-the-table suspense formula, and this earlier effort is polished to an expert gloss. The story revolves around a South American oil fire that is blazing out of control, and the only way to put it out is with a nitroglycerine blast. When it comes to transporting jerricans over miles of uneven roads, who will be responsible? “The Wages of Fear,” Clouzot’s first and most important film, is the best location to begin a study of his work.

15. Mon Oncle (1958)

His very first color film. Hulot’s disorganized bohemianism is simplistically contrasted with the Arpels’ mechanized modernistic mansion in the novel. As champion of the individual, Hulot is weirdly de-personalized.. Tati may even be a secret misanthrope, according to some. As this wonderful video meanders like the concrete garden path of the Arpels, such textbook reservations come and go. While some episodes drag on, there are plenty that are hilarious, well-observed, and always executed to perfection. When it comes to fashion, Tati has a way of making even the most bizarre of objects obedient to her exacting demands. TS

Sources: https://www.lunchbox-productions.com

Categori: Entertaiment